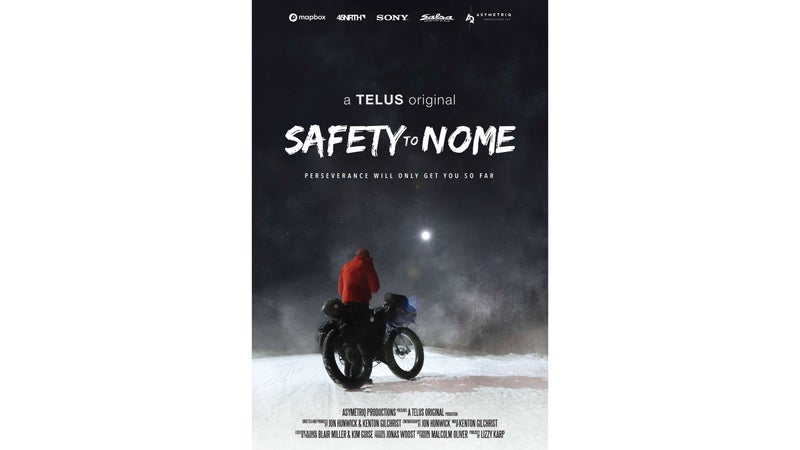

ÔÇťMore people summit Everest in an afternoon than have made it from Anchorage to Nome on a bicycle,ÔÇŁ says the╠řsummary of╠řSafety to Nome, ▓╣╠ř╗ň┤ă│Ž│▄│ż▒▓ď│┘▓╣░¨▓Ô╠řthat follows╠řparticipants of╠řthe 2017 ╠řin Alaska. The ITI is the╠řhuman-powered equivalent of the Iditarod, in which participants travel the legendary╠ř1,000-mile course via╠řfat bike, foot, or skis╠řinstead of a dogsled. And the filmmakers do not for a second let you forget just how difficult this╠řisÔÇöwhich makes Safety to Nome,╠řavailable on streaming platforms as of February 25, both╠řincredibly fun to watch╠řand an excellent meditation on why outdoorspeople like to do nearly impossible things.

Presiding over the event is ITI founder and past competitor Bill Merchant, who probably knows better than anyone╠řhow dangerous the race can be. He reminded me of ╠řin a giant parka╠řand frequently says things like,╠řÔÇťMy responsibility is to sit here and sweat blood and hope that I made the right decision when I told them, ÔÇśYes, you can come do this.ÔÇÖ What IÔÇÖm saying to that person is, ÔÇśOK, youÔÇÖve convinced me that youÔÇÖre not gonna hurt yourself or die on me out there.ÔÇÖÔÇŁ╠ř

The ITI, an annual event that╠řwill be held for the 20th time╠řon╠řMarch 1,╠řgenerally takes╠řpeople two weeks to a month to complete, and though many of the featured racers have done it before, the documentary makes it clear that experience and bravery╠řcan only get them so far. Temperatures consistently approach the negative teens. There are storms. There is snow. There is something called overflow that involves navigating a frozen lake to avoid falling into ÔÇťcrotch-deep slushie,ÔÇŁ as Merchant describes it.

The race begins with 26 competitors, but that number quickly drops as people succumb to exhaustion, chest infections, and frostbite. There is so much frostbite. At one point, a man in a beanie reports that just that morning, a piece of his ear came off with his hatÔÇöand yet, heÔÇÖs not sure if he should drop out!╠ř

The documentary makes audiences really feel the slog at times, but as the remaining racers push on, it becomes a no-nonsense examination of the attitudes that made them sign up for such an insane and Herculean task in the first place. The participants are mostly local men whose╠řviews of racing the ITI are similar; they often, for example, frame the race╠řas a form of escapism from their daily╠řlives. ÔÇťThis is still all easier than taking care of a two-year-old,ÔÇŁ says Kevin Breitenbach, who holds the lead for part of the race before having to drop out. ÔÇťI havenÔÇÖt had anyone hitting me, yelling at me.ÔÇŁ Another racer relishes that he doesnÔÇÖt have to answer his phone or reply to email╠řwhile competing. And itÔÇÖs a way to shake out of being a ÔÇťnaturally fearful person,ÔÇŁ as the sole female racer interviewed in the film puts it. ItÔÇÖs also simply a choice of what to do with your free time, several interviewees point out.╠ř

Basically, people do the ITI for the same reasons that others dedicate╠řthemselves╠řto mountaineering, ultrarunning, or any other sufferfest. But the character traits (stubbornness, fortitude, and pride, among them) that lead a person to╠řsign up for grueling outdoor challenges╠řare on much fuller╠řdisplay as╠řSafety to NomeÔÇÖs╠řracers make their way through the desolate, icy╠řAlaskan wilderness. Perhaps the filmmakersÔÇÖ wisest choice was spending╠řa lot of airtime emphasizing that each person is making a moment-by-moment decision╠řto be out there:╠řthese racers are technically able to bail before something really bad happens╠řor╠řto ask for help when they need it.

The racers, however, are not always eager to call for help.╠řIn one memorable scene, Merchant╠řdebates whether to check on a competitor,╠řTim Hewitt, who is in his early sixties. Hewitt previously completed the race nine times on foot, but this time around,╠řheÔÇÖs╠řtrying╠řhis luck on a bike╠řand is struggling. Hewitt gets stuck between checkpoints╠řfor multiple days with limited supplies, so Merchant sends a messenger out with PB&Js and Coke, with instructions to make it seem like a snack is being offered to every racer the messenger meets. Secretly, Merchant is trying to suss out whether Hewitt needs help. (He does.)

While╠řSafety to Nome doesnÔÇÖt offer revolutionary insights into the adventurerÔÇÖs psyche, itÔÇÖs extremely compelling when it comes to the complicated emotions that people have while attempting gargantuan feats.╠ř

ÔÇťThey were the little kids that wore the right shoe on the left foot.╠řBecause their parents figured it was a fight, they didnÔÇÖt want to take it there,ÔÇŁ Merchant says of the racers. ÔÇťThose are the little kids that grow up to be the people who come out here to do it theirself. And in Alaska, weÔÇÖre given that opportunity.ÔÇŁ