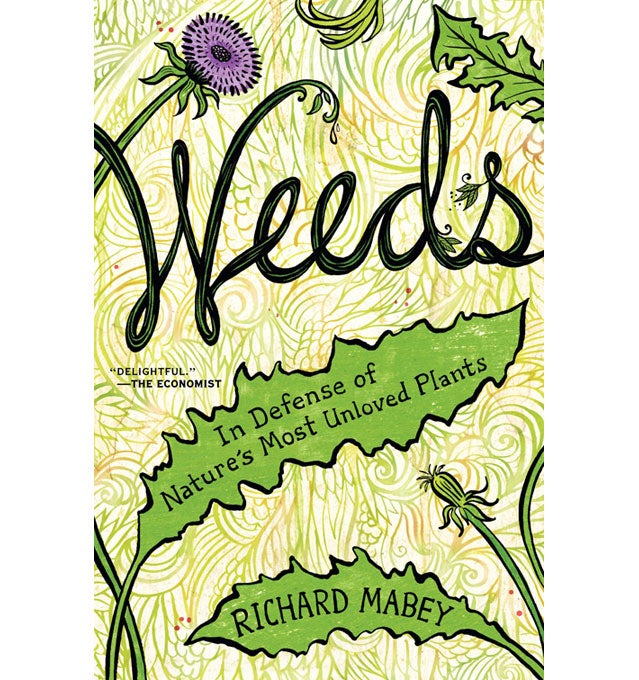

In his new book, Weeds: In Defense of Nature’s Most Unloved Plants (Ecco, $26), English naturalist Richard Mabey takes up the case of the wayward plant, arguing that what we hate about weeds—their persistence, their ubiquity—is also what makes them interesting.

The result is unexpectedly compelling. Mabey writes with a deep knowledge of botany and a clear, straightforward style. Sure, there are slow parts—I struggled with burdock, or rather his critique of 19th-century writer John Ruskin’s critique of burdock—but much of what Mabey covers is fascinating. For example: if Great Britain hadn’t brought cinchona trees, the invasive species from which the anti-malarial drug quinine is derived, on expeditions into the tropics, British colonies in India and Africa might have collapsed from illness. And the tumbleweed, a plant native not to the American west but to Russia, grows abundantly where it can blow around and deposit seeds after drying up and dying— “a classic weed strategy,” according to Mabey.

Mabey is amazed by weeds’ evolutionary skill, their ability to survive and prosper, and his enthusiasm propels the narrative. Perhaps his fondness for the plants explains why he waits until the final sections to tackle genuinely bad weeds, invasive species that not only annoy gardeners but destroy local ecologies: the Australian paperbark tree, for example, which has sucked dry vast areas of Florida’s Everglades.

Still, Mabey believes that alarm over weeds is overblown. As he aptly points out, weeds grow best in “disturbed” areas—places without established native flora. In that sense, they are a symbol of “the rigid separation of the natural world into the wild and the domestic,” according to Mabey. Or, more succinctly, weeds are “nature’s boundary breakers.”