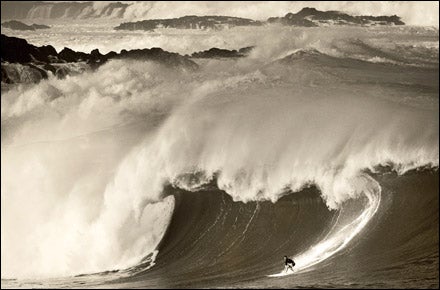

PHOTOGRAPHER ED FREEMAN is working on a book about surfing, though he’s never surfed a day in his life. A couple of years ago, while shooting stock in Hawaii, he stumbled upon some surfers on the North Shore of Oahu. He was blown away by the “athleticism, the intimate relationship with nature, and the inherent danger of it all,” he says. “I knew I wanted to do something that was art, not sports photography. I wanted the pictures to be about how surfing feels to me. Not how it is.”

Freeman readily admits the images he created were “Photoshopped halfway to death.” He spent hours on his computer, crafting the skies, combining different pictures of waves, and in one instance stitching together a Frankensurfer out of multiple riders. Two of the finished products won awards in an annual contest judged by Photo District News, a leading professional-photography publication.

When I was the photo editor at ║┌┴¤│ď╣¤═°, earlier this decade, I used to look through PDN winners for photos to publish. I’m a freelancer now, but I’m still excited to see the selections. When I first viewed Freeman’s photos this past June, I was blown away. I should have caught on that they were composites┬Śthere are some obvious clues, like overly brooding skies and myopic lighting┬Śbut I didn’t. I saw surfers riding 20-foot-tall freight trains of water and thought, These are amazing. Then I went to Freeman’s Web site and saw his disclaimer about making art images. So I did what people do these days: I posted one of his photos on my blog, .

Commenters immediately blasted Freeman, claiming he’d betrayed the sport by ginning up a photo that supposedly captures an authentic athletic achievement. Freeman replied with his own comments, shrugging off the criticism, and when I called him recently he remained unapologetic. “I’m an artist,” he told me. “I’m interested in creating great pictures, not documentary images. I couldn’t care less if they’re ‘real’ or not.”

That’s a common defense in cases like this, and a reasonable point of view. But it fails to take into account that the value of manufactured pictures is intrinsically tied to the authentic shots that came first. No matter how forthright one is about alterations, fake photos cause collateral damage. They devalue the work of photographers with the skills and patience to capture awing images in real time. Even worse, modern photo manipulation is seriously screwing up our concept of reality and our willingness to believe what we see in magazines like ║┌┴¤│ď╣¤═°.

Of course, truth in photography has always been fuzzy. The old trope “The camera never lies” is, in fact, backwards┬Śthe camera always lies. Since the birth of the medium, photographers have been crafting their images with lens selection, film type, and all manner of darkroom tricks.

“Photographs have always been tampered with,” says Hany Farid, a computer-science professor at Dartmouth College who works with federal law-enforcement agencies on digital forensics. “It’s just that the digital revolution has made it much easier to create sophisticated and compelling fakes.” Farid keeps a greatest-hits list of forgeries online, which includes a photograph of Abraham Lincoln from around 1860 that’s actually a composite: Lincoln’s head propped on southern politician John Calhoun’s body.

In the late 19th century, photographers were intent on proving that their images deserved a place in galleries alongside paintings. Like Ed Freeman, these “pictorialists” espoused the practice of manipulating photographs to achieve artistic intent. In 1932, in response to this movement, a group that included Ansel Adams formed f/64 to champion “straight” photography. Ironically, Adams was known to be a master of dodging and burning (i.e., lightening and darkening), darkroom techniques that allowed him to produce a print reflecting his vision for what the photograph should be.

Over the years, even the most hallowed curators of documentary photos have been seduced by the temptation to doctor images for creative and commercial reasons. The infamous Pulitzer Prize┬ľwinning photo from the 1970 Kent State massacre, which showed a 14-year-old girl leaning over a dead body, was retouched to remove an awkward-looking pole behind her head before being published in Life, Time, and other magazines. In 1982, National Geographic moved the Pyramids of Giza in order to run a horizontal shot on its vertical-format cover.

One of the earliest milestones in our current digital age of manipulation occurred in 1994, four years after the introduction of Adobe Photoshop, when a rising wildlife photographer named Art Wolfe published Migrations, in which a third of the images were photo illustrations. An early adopter of digital tools, Wolfe added elephants and zebras to photos and turned the heads of birds to fit his perfectionist notion of natural patterns. In the introduction, he stated that it was an art book and that he had enhanced images “as a painter would on a canvas,” but Migrations still started a stampede of accusations.

Celebrated outdoor photographers Frans Lanting and the late Galen Rowell criticized the book, with Rowell warning of the changes set into motion once the trust is broken between nature photographers and viewers.

Which brings us to our current crisis. Wolfe told me that if Migrations were published in 2009, nobody would bat an eye. “In today’s natural-history world, the idea of removing a telephone pole or lightening a shadow or removing a distracting out-of-focus branch is acceptable,” he says. Only “purists” would complain, and he “can’t even have a dialogue with them.”

That’s too bad, because some of those purists have smart ideas. Natural-history photographer Kevin Schafer argues that manipulation “waters down the power of real documentary photography.” Our reactions to a photo┬Śamazement, delight, excitement┬Śare, Schafer says, “intimately tied with its impact as a record of a real event.” This is nearly identical to the lesson that memoirist James Frey learned in 2006, when fabrications discovered in A Million Little Pieces made him a national disgrace.

When I called surf photographer and ║┌┴¤│ď╣¤═° contributor Yassine Ouhilal for his opinion on altering photos, he cited a photo he’d taken in Norway, a guy riding a wave in front of snowcapped peaks. Viewers always assume Ouhilal Photoshopped in the mountains. But he didn’t. “The biggest satisfaction I get,” he says, “is when people ask me if a picture is real, and I say, ‘Yes, it is.'”

And yet the amount of manipulated photography in circulation only grows along with the number of publications willing to push boundaries. The July cover of Outdoor Photographer is an Art Wolfe picture of Utah’s Delicate Arch┬Świth a full moon plopped in the middle. Wolfe had captured the moon with a nifty double exposure that required him to switch to a telephoto lens, but the magazine’s extended photo caption cites only the 17-35-millimeter lens Wolfe used for the shot of the arch. That would make a full moon the size of a pinprick; this one is more like a dime. (Outdoor Photographer claims the omission was an oversight.)

Equally worrisome are the insidious digital alterations┬Śused to “improve” photos┬Śwhich have become commonly accepted practice: darkening skies, oversaturating colors, and sharpening everything. These subtle but significant tweaks are now so easy that many photographers (and photo editors) do them out of habit.

David Griffin, director of photography at National Geographic, says that imperceptible digital fixes are a serious threat to integrity. He feels the sly use of manipulation in photojournalism threatens “to erode the veracity of the honest photographic covers that may come in the future.” National Geographic does permit some enhancements, like slight darkening of highlights, opening of shadows, color correction, and the removal of defects (dust and scratches)┬Śall part of what used to be industry-accepted “old darkroom techniques.” But the magazine also requires all assignment photographers to submit their images in raw format┬Śessentially a digital negative┬Śso it can oversee all the changes in-house.

That kind of policy would have prevented an embarrassing incident last year for ║┌┴¤│ď╣¤═°, which published Rod McLean’s stunning photo of sailboats on San Francisco Bay in its Exposure section. Several readers pointed out impossible contradictions in wind, light, and color, and ║┌┴¤│ď╣¤═° printed a correction. McLean, who created the image by stitching together nine shots, had told the magazine he’d retouched the image┬Śremoving a buoy, adding waves and clouds┬Śbut the editors didn’t realize the extent of the alterations. When I called him, he sounded a lot like Ed Freeman. “I’m looking at photography from my ability to create an image,” he said. “Other people look at photography as capturing a moment. Both approaches have always existed.”

McLean explained that he knows some photographers feel threatened by his techniques, but insisted that he doesn’t retouch images because it’s “the easy way out.” He noted in an e-mail that he spends hours taking photos┬Śthen spends many more crafting “seamless images that are very real.”

I don’t buy that argument, but McLean did bring up one really good point: Many of the same photographers pointing fingers at his work are quite happy to stage action for the camera. Rock-climbing photography has a particularly bad reputation in this regard. It’s common for climbers to complete an ascent on their own, then replicate the most dangerous moments with a photographer in tow┬Śalong with better lighting, more protection, and shampooed hair. Magazines typically run these images without noting that they’re re-creations. (When I was at ║┌┴¤│ď╣¤═°, we published a shot of Dean Potter on Yosemite’s El Capitan in 2002, with a caption citing his historic free climb, but omitted the fact that photographer Jimmy Chin had taken the picture a couple of weeks after the ascent.)

Christian Beckwith, founder and former editor of Alpinist, a climbing magazine defined by its pursuit of authenticity, believes that this dishonest practice “undermines the power and drama” of images capturing actual accomplishments. “Climbing photography is best when it’s spontaneous,” he says. “Those photos have much more value than an image that was created using the same climbers but with perfect everything.” The result of the race among photographers and magazines to create a better, brighter (or darker) version of reality is that “our relationship with photography is changing,” says Hany Farid. “A more savvy public is becoming skeptical of the images they see┬Śperhaps overly so. Many are quick to tag photos as Photoshopped.”

Skepticism does have an upside. One of the more positive trends taking hold is the policing of photos. Earlier this year, judges in the Picture of the Year contest in Denmark created a stir when they disqualified Klavs Bo Christensen for excessive Photoshopping in his series of photos of Haitian slums. In July, The New York Times Magazine ran a portfolio of abandoned construction projects across the U.S. taken by Portuguese photographer Edgar Martins. When the Times posted them online, commenters on the community weblog MetaFilter jumped on apparent cloning and mirroring techniques, causing Times editors to quickly pull the images.

What I think is happening┬Śwhat I hope is happening┬Śis that we’re finally fed up with all the tampering. Too many published photographs are unhinged from reality, morphed by a few mouse clicks into slick advertisements for perfect moments in time. Our relationship to photography is clearly changing, as Farid notes, but so is our taste: There’s a growing hunger for truth. We’ll never get all the way there┬Śno camera will ever see as honestly as our eyes┬Śbut the idea that photographers set out to pursue truth is about to have its moment. And it’s about time.