As he’s setting out for the west coast of Africa, travel writer Paul Theroux likens travel to dying. “When you’re only a dim memory, a bitterness creeps into the recollection, in the way that the dead are often resented for being dead. What good are you, unobtainable and so far away?” But Theroux’s writing is firmly rooted in the land of the living, and the sparsely traveled locations he writes from are exactly what make it compelling.Â

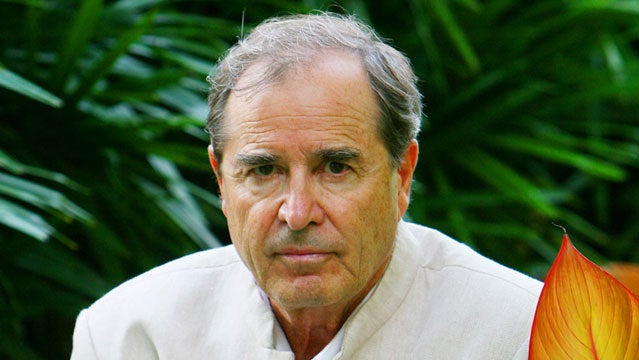

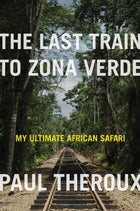

In the just-released The Last Train to Zona Verde, a follow-up to 2002’s Dark Star Safari, Theroux recounts with characteristically vivid prose one last, ambitious trip from South Africa through Angola. It may be the last he sees of the continent for a while, but it won’t be the last we hear of him. We spoke to Theroux about his nomadic career, his beef with the “big, horrible cities” of the world, and his next great adventure.

OUTSIDE: You’ve been doing this for almost 50 years now. How have your adventures changed since you first started?

THEROUX: I joined the Peace Corps in 1963 in Nyasaland, which became Malawi. That was really the beginning of my adventures in the world—I mean, the real world. At that time, African countries were just becoming decolonized. It was very hard to get to Central Africa. All in all, about five flights. I knew I was going into a country of troops and no paved roads. All that’s changed. The two significant periods I can think of are before the jumbo jet and after the jumbo jet. After the jumbo jet, travel became much cheaper, available to more people.

I understand you’re not a huge fan of planes.

Do you know anyone who is? It’s just awful. It’s a quick way of getting from one place to another, but if anyone really wants to see a country, you have to see it on the ground. You want to see Mexico, you go from Arizona into Nogales, Mexico, and travel by road. You don’t fly to Baja. I’m an advocate of overland travel. No matter where you go, there’s more reality to it. Sometimes more difficulty, but it’s not a distorting mirror of going from one national capital to another.

You seem to have a skill for finding those non-touristy places, and moments of serendipity. Where does the planning stop and the luck begin?

I think you do basic planning—you have to get yourself to the place. The advantage that I have is time on my hands. If you have unlimited time, you can go anywhere, find out things, and serendipitous things take place. I don’t do a lot of planning. I don’t look people up. It’s a question of I suppose moving on. You get on a bus, walk somewhere, meet someone—you keep moving until you create this sort of vortex of energy, and things happen. But four of the people I met died, so I also had this gloomy feeling about travel, that if you push your luck you might be making a fatal mistake.

Is there anything else you really fear on the road?

Meeting a young person carrying a gun. I do not like that. It’s happened a few times—well, half a dozen times. It could happen to you in New York City. But it could also happen to you in Kenya, in Angola. Someone pointing a gun. Everything else is sort of negotiable.

Does it change how you feel about traveling after things like that happen?

No, I’m not turned off travel. I love it, I need to do it. The things I don’t like are the big, horrible cities of the world. şÚÁĎłÔąĎÍř magazine is a proponent of adventure travel, wide-open spaces. şÚÁĎłÔąĎÍř magazine is not committed to the urban nightmare, am I right? So the trouble is that Africa, to use an example off my book, is becoming much more urbanized. It’s become going from one big horrible city to another big horrible city. There’s nothing to report. They’re places that people are trying to escape from as well as trying to get to.

What animates me is getting to a landscape that I can travel in, doesn’t matter safely or unsafely—your luck is your luck. But you want to feel that you’re not confined in a city. I want to feel that, anyway.

What do you think constitutes a successful trip?

What I look for is a sense of liberation. The fact that you’re away from home, you’re managing, making some discoveries about the place, about yourself. You just have the sense—even though it might be a struggle—of personal freedom. And then seeing things before they melt away. The world is changing, traditional life just disappears. So see it before it goes away.

That reminds me of the first chapter of the book, where you visit the Ju/’hoansi people, who were living traditional lives in Namibia. But you got the sense that they were putting on a show.

There is a certain romantic illusion that people are living traditional lives when they’re really not. There are very few places in the world that live as they used to. So that was certainly an illusion. I thought that I was seeing traditional life, not just seeing people putting up.

But you still appreciate it, even if you know it isn’t exactly real.

I met an old man and he was telling me about his life, and I thought, however false this other aspect was, at least I met this guy and he was leveling with me. One of the things that I value in travel is talking to people who remember the way things were. They may be dressed in a Chinese T-shirt and wearing a baseball hat, but they have sort of a sense of continuity that’s not obvious in the way they dress.

Is there anywhere in particular you’d still like to go and learn about that?

When I joined the Peace Corps in 1963, if I had tape-recorded, say, a 70-year-old person—they would have been 10 years old at the turn of the century. They would have remembered the First World War, the way it was fought in Africa too. No matter where it is, memory of the past; it’s extremely valuable. In so-called travel-writing, that’s what interests me. The traveler is not going to museums or churches, but actually talking to people and hearing about their lives.Â

What is it that you want to give your readers, as a travel writer?

I’m sharing my experience such as it is, no matter how trivial. I’m also doing what writers ought to do, which is to give some shape to the world. What am I doing really, writing about some far-off place? It’s just a letter to a friend, telling them what happened, and trying to be as truthful as possible. The basic pursuit is to enlighten—and also to divert.

When you decided not to complete your trip at the end of Zona Verde, did you feel you weren’t going to get that out of the rest of the journey?

I felt at the end that it would be repetitive. For some people, the metropolitan experience is very thrilling. It’s not for me. The idea of rootless people trying to leave the country, it’s not my line in writing. And I found that I was taking 10-hour bus rides from one big horrible city to another big horrible city, and I was thinking, What’s there to write about it? It would all be a complaint. You know what I mean?

In Zona Verde and Dark Star Safari, the tone does seem to take a bit of a downward turn. Some take issue with your assertion that you’re “not an Afro-pessimist”.

I don’t know what people think, but if anything, I feel positive about Africa. I feel down on people trying to save Africa, if that’s what you mean. My general feeling is a lot of people in the rescue business are really trying to rescue themselves—rescue a reputation or make themselves prominent. In the big green beating heart of Africa there’s a lot of hope, so I’m not down on it.Â

It’s the interest of a lot of people to portray others as more desperate than they really are. I’m not sentimental. All I want to do is try to see things as they are, not as I wish they were. And if you do that, you know, sometimes what you say is unpopular. But that’s my role as a writer.

It doesn’t seem like you plan on retiring anytime soon. What’s next?

When I was having an interesting time in Africa, I was thinking how little I’ve seen of the United States. What I’ve seen is, there are parts of America that resemble the third world. They have the same problems of access to health care, high infant mortality rates, serious poverty. They’re often ignored. I’m not a sightseer. I’m interested in seeing the world as it is. So if you ask, something in the South, in the Deep South.

I’ve done a bit of traveling there. I find, in general, that the people I’ve met are very welcoming. People have great stories to tell. I’m gonna give it a try.