ÔÇťI honestly believe that the future of the American public lands is as important to our nation as the Bill of Rights╠řor the Constitution itself,ÔÇŁ journalist Hal Herring declares about halfway through Public Trust, a documentary that premiered╠řat the╠ř╠řin Missoula, Montana, on February 17. Environmental ethics are often built on such provocative statements, which force people to consider:╠řDo I agree with that? If I do agree, what responsibilities do I have to act on my convictions?

Public Trust is an environmental film for this political moment. Directed by David Garrett Byars and executive-produced by Robert Redford and Patagonia founder Yvon Chouinard, it delves into╠řthe polarized environmental politics in Washington, D.C.,╠řand at state capitols throughout the country╠řbut╠řcontends that weÔÇÖre not as polarized on the subject of public lands as politicians and corporations would have us believe. Instead, it arguesÔÇöor, at least,╠řbetsÔÇöthat the vast majority of Americans favor the long-term ecological health of our parks and monuments over short-term resource extraction.╠řIt also makes a strong case that corporate interests are now actively shaping public-land policy.

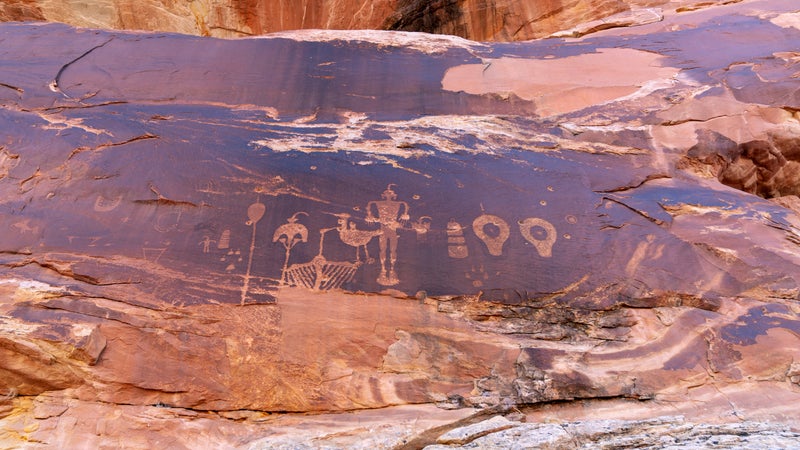

Herring, a contributing editor to , acts as the audienceÔÇÖs VirgilÔÇöif Virgil were a mountain man with an Alabama drawl. He guides us through the filmÔÇÖs three primary settings: UtahÔÇÖs Bears Ears National Monument, AlaskaÔÇÖs Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, and MinnesotaÔÇÖs Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness. We learn that conservation advocates in each location had achieved significant,╠řprotective policy advances at the end of the Obama Administration, often after long and protracted battles. Those achievements have begun to unravel under the Trump Administration, which has consistently acted in favor of industry in those locations.╠ř

Perhaps Public TrustÔÇÖs╠řcentral questions surround the rights and responsibilities of democratic citizens (or ÔÇťpublic landowners,ÔÇŁ as some in the film prefer to call them) in a country with vast and vibrant public spaces. It is not enough anymore, the film seems to argue, for us to simply appreciate the United StatesÔÇÖ 640 million acres of publicly owned land. If we want to continue to enjoy the benefits of these places and preserve them for future generations, we must start to advocate for them the way conservationists have advocated to protect the Boundary Waters, the intertribal coalition has advocated for Bears Ears, and the GwichÔÇÖin in Alaska have advocated for ANWR.╠ř

That perspective is likely to resonate with viewers who were at the documentaryÔÇÖs Big Sky premiere, and in the western U.S. more generally, where people are surrounded by public land and tend to actively engage with it. ( that voters in the West support conserving public lands over resource extraction by a wide margin.) But if you look at of our nationÔÇÖs public lands, most of those 640 million acres are located in the western third of the country, and not every American has equal access to these protected places╠řor an equally enthralled relationship with them. Public Trust╠řacknowledges that gap╠řonly to a degree: at the beginning of the film, Herring recalls moving to the West from northern Alabama, where, he says, ÔÇťthe idea of public land wasnÔÇÖt really in our vocabulary.ÔÇŁ All of the conservationists featured in the film have deep ties to the land theyÔÇÖre trying to protect; thatÔÇÖs what motivates their activism. While a single film can only cover so much,╠řit remains unclear what advocacy might look like for people who do not╠řhave a strong personal or cultural connection to protected areas╠řbut╠řare ÔÇťpublic landownersÔÇŁ nonetheless.╠ř

ItÔÇÖs worth noting that in the first several weeks of 2020 alone, as Public TrustÔÇÖs╠řproduction team was wrapping the final cut of its film, the Department of Homeland Security ecologically and culturally significant sections of Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument in Arizona to install a border wall. And the Department of the Interior announced plans to allow drilling, mining, and grazing in Bears Ears and Grand StaircaseÔÇôEscalante National Monuments (a move that would further undo the work of the activists featured in the documentary). Meanwhile, the Bureau of Land Management environmental-impact studies for future planning processes.

LetÔÇÖs hope that painting a vivid, compelling picture of public lands, and the advocates╠řdedicated to protecting them, will encourage people to fight for conservation in myriad forms, however they are able to, from afar as well as up close. Bridging that gap will be an integral part of protecting these lands for generations to come.