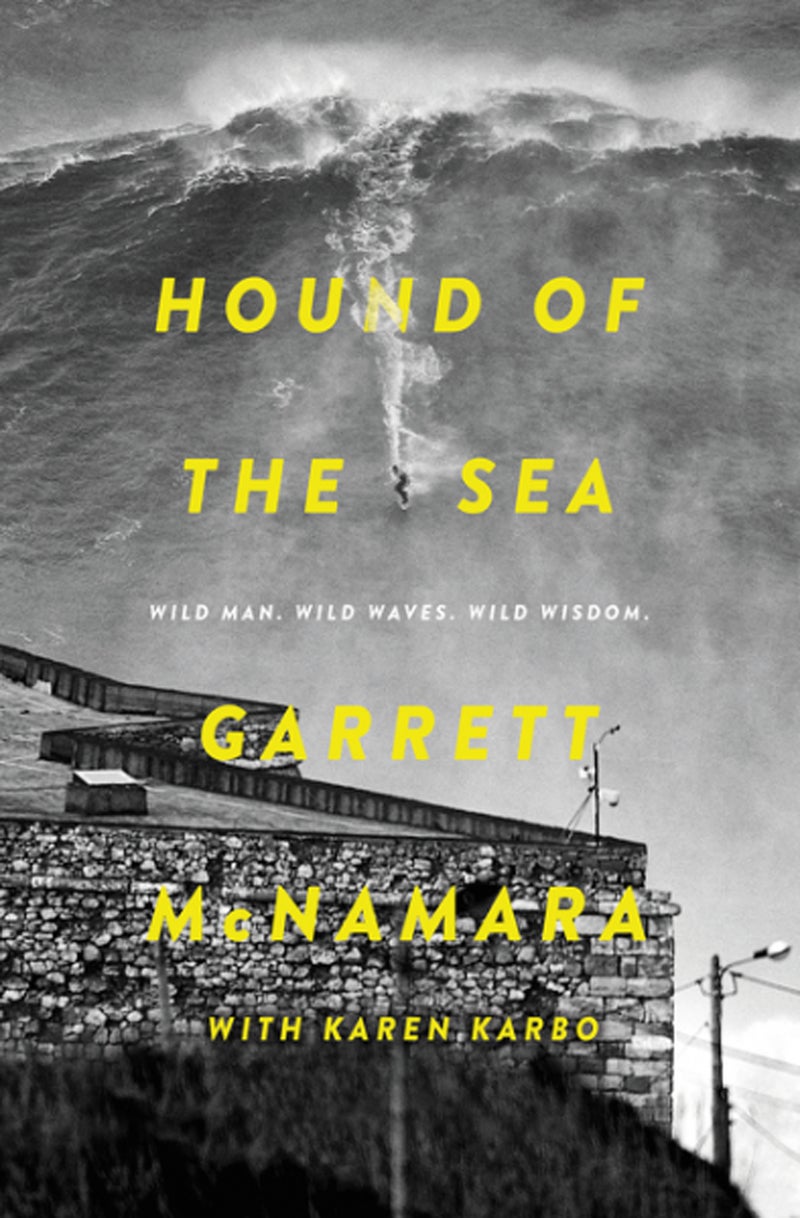

If you know Garrett McNamara for just one thing, you know him as the tiny guy on a giant (possibly 100-foot) wave in Nazaré, Portugal, an image of which made the rounds far beyond the surfing world in 2013. If you know anything else about McNamara, you probably know him as a wild-man big wave surfer��who's garnered��recognition and criticism in nearly equal parts.

In his new autobiography����($27; Harper Collins), written with author Karen��Karbo and released November 15,��McNamara tells his side of things—from his freewheeling upbringing through his rise in the world of surfing. Here's what he had to say about some of the major talking points.

On a particularly fraught day at the commune where he lived at age four:

I saw some milk jugs lined up by the shed; usually, we filled them with water there. One was only half full and I could lift it up to my mouth. I held it with both hands and took a few gulps. Something wasn’t right. My face felt scorched, nose burning, insides stinging. I, who rarely cried, yowled like the losing cat in a fight. Grown-ups appeared. I still held the jug of what was, obviously except to me, kerosene or gasoline. One of the commune moms scooped me up and took me into the kitchen and forced real milk into me. It was cold and chalky. I was dozy and nauseated. Where were my mom and dad? I don’t know. I wasn’t scared, and neither were the women holding me and forcing me to drink the milk…��

Around the same time there was a big sweat-lodge party. At nightfall someone breaks out the peyote. That was is how you knew it was a happening and not just a regular get-together. Pot was the everyday drug of choice, but peyote was for special occasions. Like the milk chocolate, the button fits snug in my palm.��

Down the hatch.��

It doesn’t taste any different than a lot of the other stuff I pick up off the ground and eat, bitter and earthy. But suddenly everything that had been on the inside of me was on the outside. A geyser of pink and brown spews out of me. Watermelon and chocolate and peyote.��

On his brother Liam’s reputation in the surfing world:

Every professional surfer on earth is there, and he somehow believes he deserves a wave because he’s spent a lot of time dreaming of, say, Pipeline, and he’s spent a lot of money to get there. And the photographers want to make their careers getting a great shot of him, and his sponsor, say Billabong, will feature the photo in a full-page ad in one of the big surf mags. A lot of people, not just the surfer, have a lot riding on him catching the wave of any given day.��

But Liam has been here month in, month out, waiting. Pipeline and Rocky Point, the breaks he surfed religiously, the breaks he was working in an effort to have a solid career, were and are the most photographed breaks in the world. And, as a result, the most crowded.��

This is where the challenges began for him. He was not about to step aside so that some pro who’d just stepped off the plane in Honolulu three hours earlier could take a good wave. Especially in contests, when all eyes were on him, he would go for it.��

Writers writing their stories in the surf mags didn’t help matters. Neither Liam nor I were sponsored by the magazines’ big corporate advertisers. We didn’t ride for Billabong, for example, so we were easy scapegoats. Stories need a villain, and Liam was as good as any, especially because he was unrepentant. Why shouldn’t he be? There were California surfers who were blond and laid-back, and there were Aussie surfers who were radical and hard-charging, and there were noble and revered Hawaiians who could be as gnarly as they pleased because the entire world was encroaching on their perfect and unique waves, and there were eccentric South Africans and a few mysterious Tahitians, and there were drugs and there were feuds and choke outs and all the drama of any insular world, but there were no real bad guys. There were badasses, there were bad boys, but no bad guys. Except for Liam McNamara.

It was unfair. For refusing to play by the very specific rules of the lineup, he was offered up in the service of controversy and drama. He sometimes complained that the judges of the contests were prejudiced against him, and who’s to say they weren’t? His entry in Matt Warshaw’s respected Encyclopedia of Surfing says he’s “often mentioned as the sport’s most disliked figure.” I lived under his shadow, the brother of Liam. People who didn’t know me disliked me. Even though I tried to stay out of the lineup when Liam was there, I felt the chill whenever I paddled out.

On the “much-discussed” Portugal ride that won him the 2012 Billabong XXL Award for Biggest Wave of the Year:

The surfers’ code is that you surf your wave and let the world discuss it as you move on to the next one. That I was doing exactly that was lost on people. I never said a word about how big or small I thought the wave was. I didn’t ask the good Kelly Slater to , nor did I know anything about any public relations firm. I didn’t have a publicist. I had my love Nicole helping me. Still, it was generally assumed that I or someone I’d hired was breaking the code and claiming, bragging, about my ninety-foot wave.

Weirdly, I was also held accountable for the awkwardness of the mainstream media people who covered the story. CNN sportscasters don’t generally report on surfing, and I think they can be forgiven for sounding dorky when they say “That was completely gnarly!”, but many in the surf world found this to be heinous. By surfing my big, strange, off-the-beaten path wave I’d drawn the attention of kooks and outsiders. The surfing media made their feelings known about the whole thing by ignoring both the wave and my ride. I was upset by this not at all. My goal was simply to ride the biggest wave I could find, and also to show the world, not just the small surfing community, that Nazaré was (and still is) the only place on earth where an average person can experience the power and energy of a wave of this magnitude safely from shore.

Then, in May 2012, the jury came back and my ride . The final measurement was seventy-eight feet, a mere foot taller than Mike Parsons’s 2008 Cortes Bank ride…

I was honored and humbled that the panel didn’t let politics cloud their ability to judge me fairly. After I made my comeback in 2002 and , the eyes of the surfing world were on me in a way they’d never been before. When I took off on nearly vertical waves that no one else would touch, people assumed I had no fear. When they watched me suffer epic wipeouts then come up smiling, it was decided I had a screw loose. When I , I got a bad rap as a crackpot and attention seeker. …

To acknowledge that the biggest wave in the world might be a shore break off a little Portuguese town no one has ever heard of flies in the face of what passes for reason in the surf world. That it was ridden by Garrett McNamara, daredevil-cowboy–action figure–future Fear Factor contestant–brother-of-etiquette-challenged Liam (I’m missing a few adjectives, but you get the picture), is to commend the integrity of the judges. I was and am grateful.

On witnessing Greg Long’s near-death experience at California’s Cortes Bank in December 2012, for which many criticized McNamara’s involvement:

Two days later Greg to the press explaining what happened and thanking everyone who saved him. He acknowledged the high level of risk involved in surfing big waves, and at Cortes Bank in particular. He never mentioned my name, but he didn’t have to. The surfing press was already buzzing, accusing me of dropping in—the most heinous crime in surfing—and further raking me over the coals for using the WaveJet, an invention I’ll always defend because it gives folks who might otherwise never have the opportunity a chance to experience the exhilaration and pure joy of riding a wave. Some surfers just need a little extra speed, but there are also people like Jesse Billauer, a California surfer who became a quadriplegic at seventeen when he broke his neck during a wipeout, who’ve been able to surf again unassisted using WaveJet technology. It’s also been adopted with enthusiasm by lifeguards, since the WaveJet allows them to reach drowning swimmers faster.

Surfing purists, who would have us all surfing on planks of wood and wearing loincloths, despise pretty much all technological advances in the sport, and wanted my head. During interviews surf journalists, who are supposed to be impartial, prefaced questions with stuff like, “Garrett McNamara . . . essentially cut him off. And on top of that Garrett McNamara was riding a WaveJet. Those things repulse me. I am not a big fan of WaveJet at all. I don’t think they belong in the lineup. That’s just me. What’s your take on it?”

The comment sections of every surf news report and blog post of the incident bristled with stories of what a monster I was, of how I’d dropped in on them in two-foot waves fifteen years ago at a place I’d never been to and practically killed them. If I’d dropped in on all the people who said I’d dropped in on them, I would have been banished from the sport long ago.

Even though Greg kept reminding the world that big-wave surfing, especially at a place like Cortes Bank, is a high-risk activity and what happened to him was not unexpected and that he’d trained for such a thing for years, someone needed to take the heat. Someone needed to be blamed.

I telling my side of the story and apologizing for any part I may have played. It fell on deaf ears. Three weeks later, in early January 2013, Greg issued another statement saying that I wasn’t to blame. That only served to make him seem more gracious, to whiten his hat and blacken mine.

On the Nazaré wave that put him back in the spotlight in 2013:

The picture is amazing. The angle makes it look bigger than it is and from a purely photographic perspective the Nazaré wave has an advantage that no other monster wave possesses—it can be compared to something other than the little surfer at the bottom of it. The viewer sees the lighthouse perched high on a cliff and thinks, What is that, eighty feet up? And the wave looks even taller. It requires no leap of the imagination. It’s something everyone can relate to. The viewer thinks, That could be me standing on the roof of that lighthouse. Holy shit!

The picture went viral. The media kept pumping it up as the hundred-foot wave no matter how much I said that it was an intense swell to ride but I’m not sure it was even a wave, technically, and I have no idea how big it was anyway. Really, no one cared what I said.

Predictably, the surfing world lost its mind over my “claiming,” even though anyone who cared to click around a bit for ten minutes would see I had nothing to do with it. Likewise, bitter, would-be surfers who sit in an office all day more or less dismissed Nazaré as having any kind of viable waves, much less a world-class giant. In fairness, some of the good guys stepped up and acknowledged that I’d achieved something most surfers dream about—discovering and pioneering a new wave and making a career out of surfing. South African big-wave charger Grant “Twiggy” Baker, 2014’s Big Wave World Tour champion and a regular at the XXL Big Wave Awards, admitted that what I’d accomplished was “every man’s dream.” But there was also the usual bad press. I was used to it by now. All that daily practice of acceptance.��