For decades,╠řa plot of federal land in southeastern Arizona called Oak Flat has been at the center of a fight over resource extraction. Since 2005, a mining venture has been pushing the U.S.╠řgovernment to let it╠řexcavate the siteÔÇÖs copper ore, which was discovered in 1995. The potential consequences of the mine╠řgo far beyond the estimated of waste╠řit╠řwould produce:╠řit╠řwould destroy land that has been╠řsacred to the San Carlos Apache tribe╠řfor generations.╠řOak Flat, called╠řChichÔÇÖil Bildagoteel╠řin the Apache language,╠řwould quite literally collapse into a void; if that happens, ÔÇťour spiritual existence will be threatened,ÔÇŁ╠řtribal chairman Terry Rambler says╠řin , Lauren RednissÔÇÖs╠řnew book about the conflict.╠ř

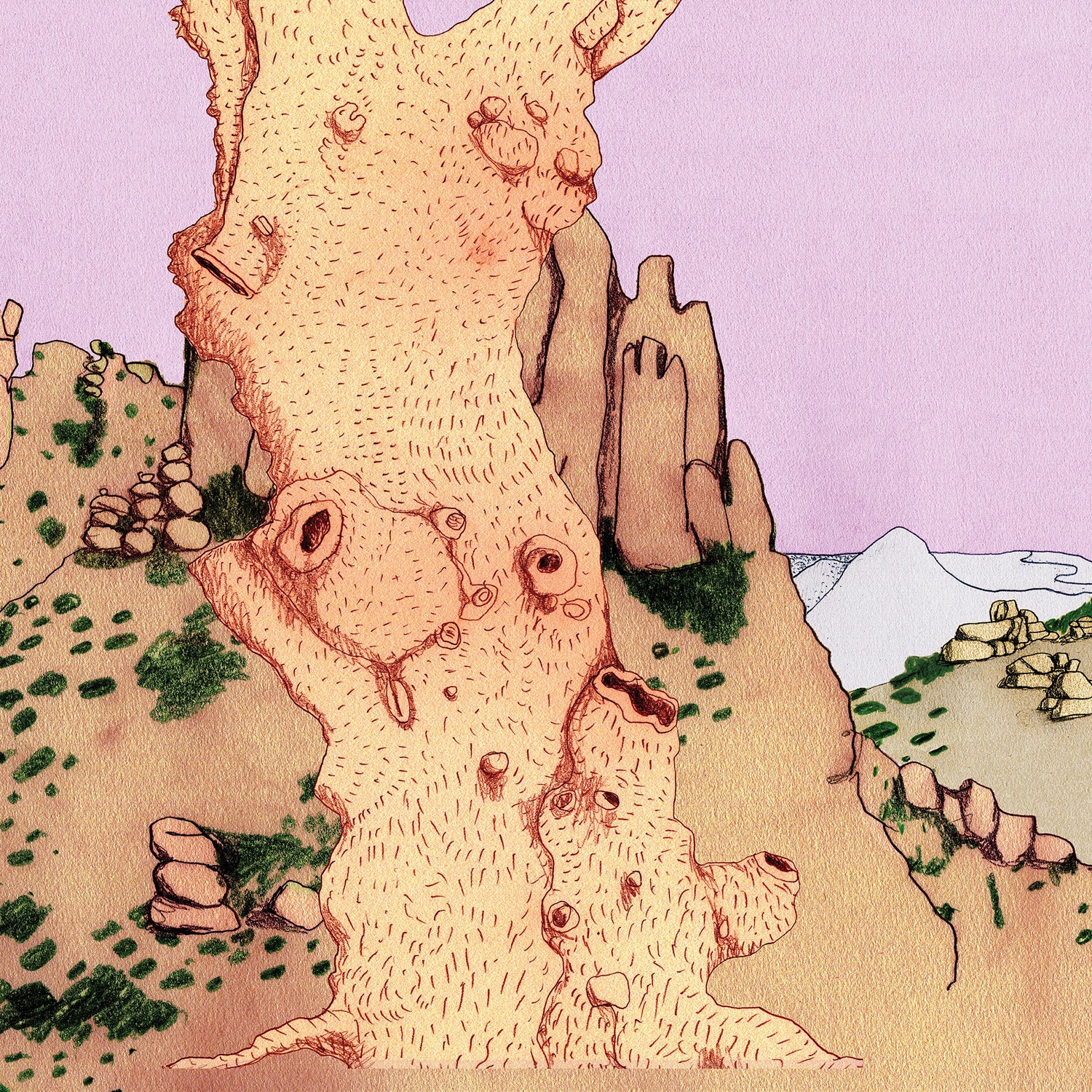

Oak Flat╠řtakes a unique approach to the difficult task of putting the╠řstakes of this conflict╠řto paper.╠řLike RednissÔÇÖs three previous books, which focus mainly on science and history,╠řOak Flat╠řcombines intensive reporting with RednissÔÇÖs own illustrations and design touches. Pages filled with╠řhistorical detail╠řor snippets of interviews are accompanied by╠řhand-drawn portraits and sometimes give way to more surreal illustrations and poetry-like musings. As a nonfiction graphic novel, Oak Flat╠řmakes centuries of history feel immersive and concrete, managing to╠řgive╠řproper╠řweight to everything that stands to be lost along with the land, and showing╠řjust how deep injustice runs when Native Americans fight to protect whatÔÇÖs theirs.

Redniss became interested in writing about Oak Flat in 2015╠řafter reading a short in The New York Times╠řabout the land-transfer debate. There wasnÔÇÖt much mention of the people who would be affected, she remembers. Her own reporting would come to revolve around those╠řwho live on the San Carlos Indian Reservation and in the nearby town of Superior. She spent the next five╠řyears getting to know a family with╠řmultiple generations of activists: Wendsler Nosie, his daughter Vanessa Nosie, and her three school-age╠řdaughters, Naelyn Pike, Nizhoni Pike, and Baas├ę-O Pike.╠řRedniss also spent time with local families who have worked in the mining industry for decades. ÔÇťWhether they support the mine or are against the mine, I wanted to understand their lives and their challenges and their reasons,ÔÇŁ she told me. ÔÇťI didnÔÇÖt want to paint individuals with blame. I think that what we can hold accountable is the government and the corporations.ÔÇŁ

When it came time to write, Redniss, who is not Native American,╠řwanted to make sure she presented stakeholdersÔÇÖ voices in╠řas unmediated╠řa way╠řas possible. She devotes many pages to╠řtranscripts of conversations with the Nosies and to NaelynÔÇÖs testimony at a congressional hearing about Oak Flat in 2013. She contrasts the PikesÔÇÖ╠řincredible activism with their everyday lives as teens and preteens. (At one point, Naelyn posts on Instagram, ÔÇťIÔÇÖm just a modern day Apache female warrior fighting for my people against corporations trying to take over mother earth!ÔÇŁ) Throughout Oak Flat, Redniss takes care to let the familyÔÇÖs╠řsense of humor and closeness come through.

The book is, in large part, about bearing witness to the religious and environmental significance of the land. Oak Flat is known to Apaches as the home of the Gaan, or mountain spirits, and is the location╠řof many ceremonies. The land holds some of the best-preserved Apache archaeological╠řsites, as well as untouched flora and fauna like old-growth trees and threatened species like╠řocelots, which Redniss╠řdraws╠řin realistic detail. She returns often to the Sunrise Dance ceremony held on Oak Flat for every girl when she reaches puberty, depicting╠řthe dance╠řwith portraits of the womenÔÇÖs faces╠řor illustrations of the event in deep red tones. (Such dances were by the Department of the Interior╠řand held in secret for a time in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.)╠řToward the end of the book, Naelyn speaks again to members of Congress, telling them that ÔÇťOak Flat sets a precedent for all sacred sites.ÔÇŁ Redniss╠řthen guides us through sweeping illustrations of each site as Naelyn names them: HawaiiÔÇÖs Mauna Kea, New MexicoÔÇÖs Chaco Canyon, South DakotaÔÇÖs Black Hills. ÔÇťIf these sacred lands are gone, who are we?ÔÇŁ Naelyn asks.

The ongoing battle over╠řOak Flat╠řis a helpful demonstration of the (often deliberately) confusing political maneuverings that make extractive industries so hard to fight. In 2014, some members of Congress to sneak in╠řa land exchange that gave Oak Flat to the mining company Resolution Copper. President Obama then signed it into law. The Forest Service has since been inching along with an environmental impact statement on the proposed mine; simply publishing the document would legally mandate that the land be transferred to the mining company within 60 days.

Since Oak Flat went to print, the situation has sped up considerably. In recent months, the outgoing Trump administration has been for the environmental╠řimpact statement╠řso that the land transfer can be triggered before the Biden administration takes over.╠řAlthough itÔÇÖs not clear whether the president-elect would save Oak Flat if the process were delayed until he takes office, he has ╠řto work more closely with tribal leaders.╠řIn early January, the Forest Service it would proceed with publishing the environmental impact statement by January 15, despite multiple objections from the Advisory Council╠řon Historic Preservation, one of the federal agencies consulting on the land exchange,╠řthat it hadnÔÇÖt adequately consulted with the tribe.╠řOn January 12, , a group led by Wendsler Nosie, the federal government in an attempt to stop the land transfer, they hadnÔÇÖt been given proper notice about the review and that their religious rights were being violated.

Oak Flat translates this aggravating world of red tape and tedium╠řinto a thoughtful, often beautiful,╠řand deeply human story. The book manages to do justice to Oak Flat as its own universe of nitty-gritty legal details and clashing interests, but one thatÔÇÖs also representative of broader dynamics and abuses that have played out in America for centuries. At seemingly every turn in the history of the fight, there is bureaucratic nonsense, disingenuous political grandstanding, and evidence of the blatant disenfranchisement of Native Americans. ÔÇťWe think of the history of the United States as a history of conquest and treaty violations,ÔÇŁ Redniss says. ÔÇťAnd what we see here is that itÔÇÖs not just history.ÔÇŁ