Cold-calling writers I admired and offering them assignments was impertinent and I knew it. I built up my nerve before making a call by telling myself what I liked about their writing. And I wouldn’t call without a story idea that I could be specific about. This worked out more often than not if I followed up right away with a letter and contract in the mail. Sometimes the hardest part was getting the phone number.

Ed Abbey didn’t have a phone but was easy to recruit, once I tracked down his post office box in Oracle, Arizona. His novel The Monkey Wrench Gang was then the defining document for the wild-ass splinters of the environmental movement as it turned belligerent—birthing the militant Earth First! and Sea Shepherd. More important to me, his first nonfiction book, Desert Solitaire, read like observational sorcery, which is the kind of language Ed would make fun of but it’s what I told him when he called me collect after getting my postcard offering whatever assignment might interest him.

“The last thing I need is another editor,” he said. “But I suppose I could use the money.”

This was in 1977, when I was at ���ϳԹ���, and for the next ten years Ed and I usually had a piece going or at least percolating. He was a prickly edit, but funny about whatever I suggested, which always involved him writing more. He was usually on the road and I’d call him at a prearranged number, a bar pay phone in Moab, Utah, or wherever, and we’d talk through the piece. A week later I’d get whatever I’d asked for in the mail.

We got together in person for the first and only time two years later, when Ed visited me in Denver, where I was editing Rocky Mountain Magazine. “Passing through,” Ed said, but he was also making a speech at the University of Colorado in Boulder. I was living in a solid little red brick house just south of Colfax Avenue, where the Denver dive bars and strip clubs were then.

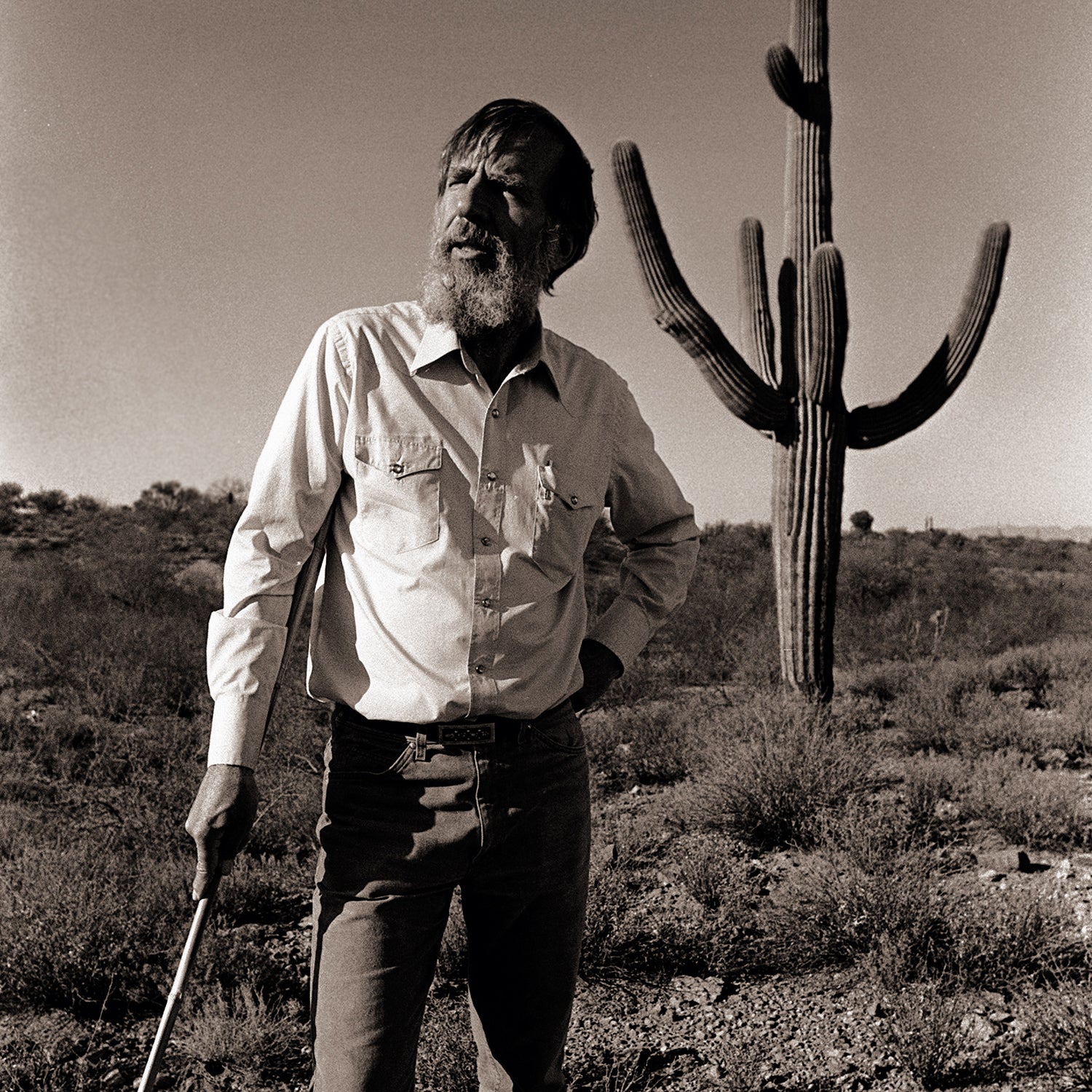

Ed didn’t call first, just rang my doorbell. Much taller than I expected, standing on the porch with a cragginess that didn’t make him ugly, but he was not handsome, either. He looked strong and difficult and more than anything like the cowboy he always insisted he wasn’t. An anarchist was what he was, from the confusingly named Indiana, Pennsylvania, who had left home after high school to find, as he put it, the West of my deepest imaginings—the place where the tangible and the mythical became the same. He could write cowboy better than anybody.

Someone at the table suggested that Ed had become a “philosopher of nature,” but it was clear to me when I caught his eye that Ed wasn’t feeling very philosophical.

Ed’s early novel The Brave Cowboy became the last black-and-white cowboy movie, Lonely Are the Brave, starring Kirk Douglas, who said it was his favorite film. I saw it on television not long after my first conversation with Ed. It was the kind of movie that made romantics want to mount up—about a young cowboy at odds with modern society, rejecting technology, cutting down barbed wire, and as true to the West as sage. When his friend is locked up for refusing to register for the draft, he gets himself arrested, in order to break his friend out of jail, but winds up on the run on horseback, with helicopters chasing him. It does not end well, but Ed’s cowboy is true to himself (refusing even to carry a driver’s license or Social Security card) and wildly heroic. By the time Ed was standing on my porch, however, he was writing and giving speeches about how the beef industry’s abuse of our Western lands is based on the old mythology of the cowboy as a natural nobleman, the most cherished and fanciful of American fairy tales.

Ed said he had been asked to speak about something goofy like “literary environmentalism” but that he always just talked about whatever he felt like when the time came and nobody ever seemed to mind. He was to appear the following afternoon on the University of Colorado campus, but tonight he was invited to a dinner party at the home of an important academic who had something to do with him getting invited to speak. After my deputy at Rocky Mountain, Karen Evans, came by my house for a drink, Ed insisted that we both go with him to the dinner. Karen, a polished woman with beautiful style, was skeptical, saying we would be imposing on what was surely an important dinner party for someone. Probably seated. Ed said he didn’t “give a hoot.”

The hostess, a young academic wife in a short skirt, met us at the door with a smile for Ed—and wary accommodations would be made for Karen and me. Among the faculty guests, we met a handsome young guy in hiking boots and a tweed blazer who said we should give Buddhism a try. I thought try was a peculiar word to use, but Karen said he probably meant meditation, not Buddhism. Ed, meanwhile, was being monopolized sequentially by our host, an older professor, and the other important PhDs. After more than an hour of drinks, we were all squeezed around a long table under a bright chandelier in a formal dining room.

Ed was at the head of the table, Karen and I next to each other on extra chairs wedged in at a far corner. Carefully seated up and down were obviously well-meaning people, and I inferred from the small talk that they wanted Ed to tell them about the spiritual importance of nature and the enlightenment he’d found as a backcountry ranger in Arches National Monument, in Utah, when he was writing Desert Solitaire.

One of the guests had a first edition that I could see had passages underlined on many pages, and he knew some of them by heart. He wondered if Ed could expand on his idea that There are no vacant lots in nature. Better yet, could Ed tell the table what he was thinking when he first saw the flaming globe, blazing on the pinnacles and minarets and balanced rocks. It was impressive, but Ed just shrugged and said, yes, that’s what he had written. Someone else suggested that Ed had become a “philosopher of nature,” but it was clear to me when I caught his eye that Ed wasn’t feeling very philosophical.

Finally, in response to an achingly long question about the importance of saving the beauty of the desert canyons, Ed asked about what he had heard to be excessive drinking, drug use and sexual promiscuity among the Buddhists at their nearby Naropa Institute. It was a question to silence any dinner party, especially one with Naropa connections to some of the guests. But then, as several people finally pointed out in a low-key but surprisingly aggressive chorus, there really wasn’t much to all those rumors. The young Buddhist in the hiking boots said he could vouch for that, but his voice broke when he tried to say something about being misunderstood himself.

“Well, then, just kidding,” Ed said, to everyone’s relief, but he was not smiling.

Changing the subject, someone asked Ed to characterize his work—what was he going for in his writing? Ed frowned and said that wasn’t his job. “Maybe you should ask Terry,” he said, disappointing everyone. “He’s the editor.”

This surprised me a little, but then I stepped into it. “Ed’s a dangerous writer,” I said, probably taking another drink. “He scares people like you.” It was a belligerent thing to say, and I was immediately sorry, but there it was. I think I then made some preposterous jump from the environmental movement to the anti-war movement and the Black Panthers and back to the radical environmental movement that Ed had inspired with The Monkey Wrench Gang. The table was turning from surprised to resentful, but now Ed was smiling.

“The Black Panthers are criminals,” our host said. “ ‘Thugs,’ ” he had read in the Saturday Review.

I said the Panthers did a lot of good things, although some of them were gangsters for sure.

“And you know all about that, I suppose,” said our hostess.

“I was in SDS at Berkeley,” I said, compounding my silly truculence.

“How unattractive,” said our hostess.

My memory of the details of what followed fails, but I may have mentioned Tom Wolfe’s Radical Chic & Mau-Mauing the Flak Catchers. Perhaps I said something more aggressive. What I do remember, distinctly, was the reddening beautiful face of our hostess.

“You’re insulting,” she said. “You should apologize to everyone here, including our guest of honor.”

“I should just go,” I said. “I’m sorry to have ruined your dinner.”

The hostess smiled tightly and stood up, making it clear that this would be fine with her. Karen and I stood up too, but all eyes were on Ed.

“Well, then,” he said, also rising. “I’ll be going, too.”

What shits we were, I thought, getting into my car, and I could see that none of us were feeling especially noble. Ed said he thought that the Buddhist kid had been about to cry, and he was sorry about that because he kind of liked Buddhists. Academics not so much. “I only asked about Naropa because I was interested in the sex,” he said.

We drove to one of the bars on Colfax Avenue, and ate pickled eggs and drank boilermakers. Ed spent the night at my house, and we were up late, talking radical talk about what was wrong and maybe a little right with blowing up dams to save rivers. The Monkey Wrench Gang was about that, and so was Jim Harrison’s A Good Day to Die, an earlier novel Ed admired. None of this was ironic except that Ed did say what he was thinking when he first saw the flaming globe, blazing on the pinnacles and minarets and balanced rocks. He said he hadn’t been thinking at all.

He also said he thought the FBI might be keeping a file on him because when he was in college at the University of New Mexico he had posted a letter urging other students to throw away their draft cards. “How paranoid is that,” he said, and poured another drink.

Toward the end of his life, when Ed’s FBI file became public he told friends, “I’d be insulted if they weren’t watching me.”

Not long after, I sold a novel and left Colorado and Rocky Mountain Magazine for Montana, where I planned to write for a while. Ed approved and blurbed the novel when it came out, saying, with his characteristic kindness to other writers, that “California Bloodstock is most stylishly composed, in the cool, nihilistic manner of Joan Didion.”

Ed knew I loved Didion, and I loved nihilistic too, because it was not one of Ed’s words and he had obviously thought about it—even though he’d just been composing a blurb. His own writing was never that mannered. He hid the craft but never the beauty of the words—words like chaparral and blue columbine and mosquito—that he set in place, all in the voice of an outraged populist poet. Ed was against development and tourism and earnest engineers, nostalgia for the lost America, cattle shitting in the watersheds, daily routine, and, in his own words: the insufferable arrogance of elected officials, the crafty cheating and the slimy advertising of the business men . . . the foul, diseased, and hideous cities and towns we live in, the constant petty tyranny of automatic washers and automobiles and TV machines and telephones!

I reread Ed often, like I did Mark Twain, grinning at the contrarian spirit and showmanship. He threw homilies like roundhouse punches: One man alone can be pretty dumb sometimes, but for real bona fide stupidity, there ain’t nothin’ can beat teamwork. He didn’t talk like that, but he wrote that way when it served his purpose—like here, from A Voice Crying in the Wilderness that he published in 1989: When a man’s best friend is his dog, that dog has a problem.

As the Other Bob Sherrill would sometimes say when he liked the way the words worked: “There is a small revolution going on in that sentence.”

Search for Edward Abbey on the FBI website and you can find a 1952 memo from J. Edgar Hoover outlining “A Loyalty of Government Employee investigation” to be conducted when Ed was working for the National Forest Service. It was triggered by that college letter about throwing away draft cards. Ed was on the FBI’s watch list from then on, and when I looked it up years later I found notations like “Edward Abbey is against war and military.” And the agency continued adding to his profile, keeping track of him, although probably not at Boulder dinner parties. Toward the end of his life, when Ed’s FBI file became public he told friends, “I’d be insulted if they weren’t watching me.”

The day Ed died in his home, Fort Llatikcuf (read it backward), near Tucson, close friends put his body in his old blue sleeping bag and loaded it into the bed of a pickup packed with dry ice. After stopping at a liquor store in Tucson for five cases of beer and some whiskey to pour on the grave, they drove deep into the Cabeza Prieta desert—all according to Ed’s wishes, and disregarding all state burial laws.

I want my body to help fertilize the growth of a cactus or cliff rose or sagebrush or tree, Ed had written. And for his funeral: No formal speeches desired, though the deceased will not interfere if someone feels the urge. But keep it all simple and brief. He also requested gunfire and bagpipe music, a cheerful and raucous wake, and a flood of beer and booze! Lots of singing, dancing, talking, hollering, laughing, and lovemaking. Doug Peacock wrote later in ���ϳԹ��� that the last time Ed smiled was when Peacock told him about the place he had come up with for Ed to be buried.

That location remains secret, but there is a hand-carved marker on a nearby stone:

����ɲ�������

�ʲ��ܱ���

�����������

1927–1989

NO COMMENT

Karen Evans had stayed in loose touch with Ed and interviewed him by mail not long before he died. I don’t think that interview was ever published, but I found Ed’s long letter to her in a posthumous collection of his correspondence, Postcards from Ed. Apparently, like the guests at that unfortunate dinner party, Karen had asked him to characterize his work and what he was going for in his writing. But Ed liked Karen, and he answered:

What I am really writing about, what I have always written about, is the idea of human freedom, human community, the real world which makes both possible, and the new technocratic industrial state which threatens the existence of all three. Life and death, that’s my subject, and always has been—if the reader will look beyond the assumptions of lazy critics and actually read what I have written. Which also means, quite often, reading between the lines: I am a comic writer and the generation of laughter is my aim . . .

. . . I now find the most marvelous things in the everyday, the ordinary, the common, the simple and tangible. For example: one cloud floating over one mountain.

At the end of the letter, Ed instructed Karen to revise and colloquialize what he had written, as she saw fit, to make it read like a conversation. It was all up to her. And she could write and ask for more if she thought she needed it. Or Karen could just come to Tucson for a day or two, because it didn’t look like he was going to be getting out of there that summer.

From the book THE ACCIDENTAL LIFE by Terry McDonell, copyright 2016 by Terry McDonell. Published by arrangement with Alfred A. Knopf, an imprint of The Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC.