About a third of the way into ($30, W. W. Norton), author Steve Kemper addresses the lure of gold rushes during the late 19th century by noting, “Sometimes reality matched imagination.” The same is true of the book’s subject, Frederick Russell Burnham, whose life was so full of derring-do and fearless exploits that, lacking historical record, one would assume him to be myth, more Man with No Name than Wyatt Earp. Burnham manages to make them both look like armchair cowboys.

During his teenage years in the 1870s, Burnham tracked the Apaches then fighting in the Arizona Territory. He once ran 22 miles over rugged terrain to deliver a message—and got there before a horseman who had left at the same time. Then he discovered enough gold in the Southwest to make him rich. Later, while traveling in what was then Rhodesia, he rode through an enemy camp of several thousand Ndebele warriors in an attempt to capture their king, was quickly surrounded, and escaped under cover of night. His gold fever not yet cured, he joined the Yukon gold rush. All this before he turned 35. (He lived to be 86 and barely let up.)

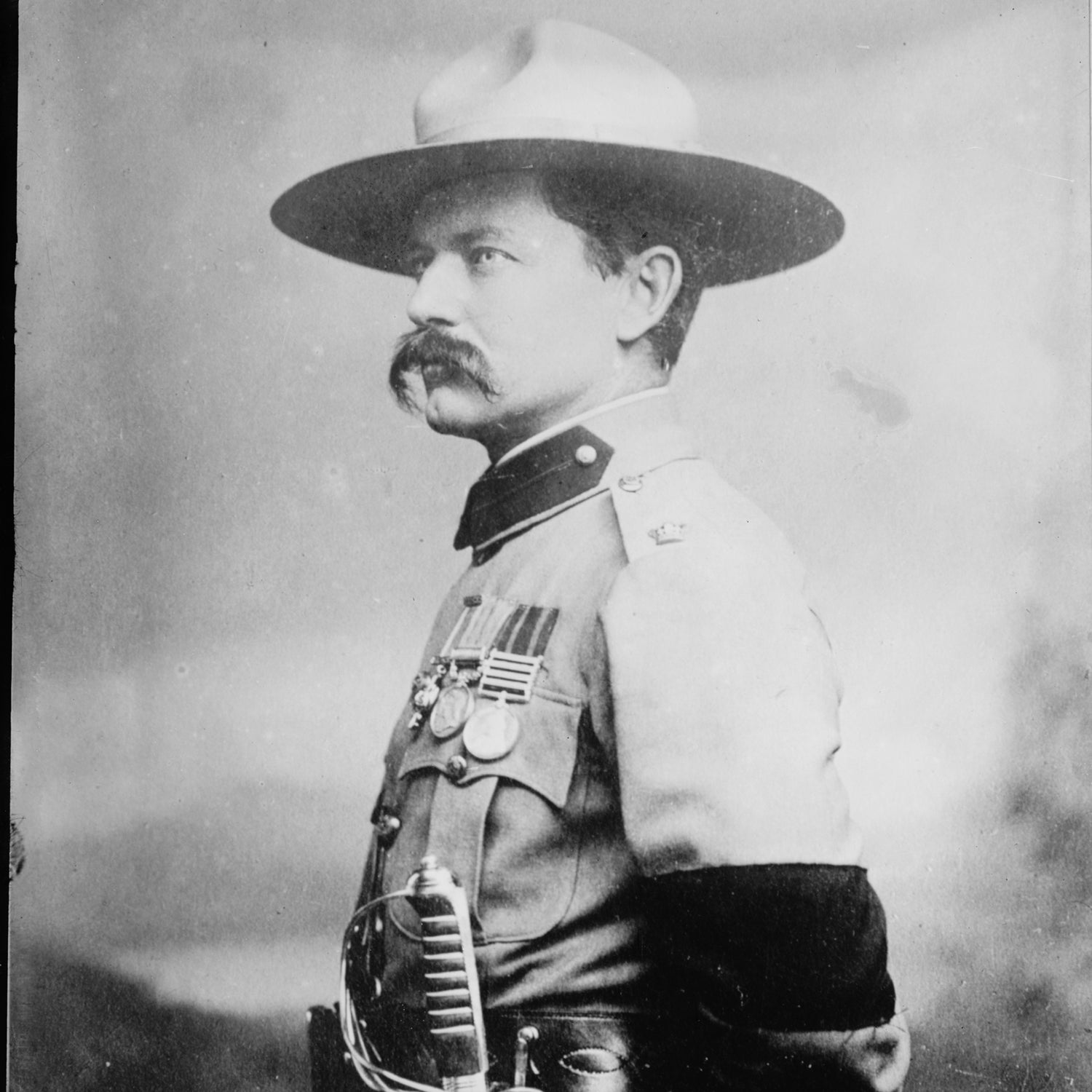

Burnham’s escapades make for easy story-telling, but Kemper’s writing is steady and fun. About Burnham’s time as a “messenger” for Wells Fargo wagons, Kemper writes, “The message was double-aught buckshot delivered from a sawed-off shotgun, a combination that could blow a window in a bandit.” Kemper writes in awe of Burnham’s skills as a scout, which were so well-known that he helped inspire the founding of the Boy Scouts of America and was asked to join Roosevelt’s Rough Riders.

That’s not to say that Kemper glosses over the man’s imperfections. He was a racist, and his wife and his three children, whose births he missed, were often left alone. But one tends to skip over those parts in search of his great adventures, which are only occasionally interrupted by lengthy asides on subjects like the short-lived . Such digressions would be distracting were Kemper not so clearly having a good time writing about them, which makes the topics almost as fascinating as Burnham’s life. Almost.