I GREW UP in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan, which is essentially a New England–size forest with the population density of Siberia. As of this writing, the U.P. has coughed up a Major League pitcher, a couple world-class coaches, and exactly no movie stars, film directors, celebrity chefs, giants of finance, or (as far as I know) porno queens. Its sons and daughters, by and large, dream feasible dreams. For the U.P.’s young writers, though, it is a little different. This difference is largely due to Jim Harrison, who has been publishing fiction and poetry about the U.P. for the past 40 years, a good deal of which was written in a cabin up near Grand Marais, a two-hour drive from Escanaba, the ore town in which I grew up.

Harrison once nastily described Hemmingway’s work as a “woodstove that didn’t give off much heat.”

Harrison once nastily described Hemmingway’s work as a “woodstove that didn’t give off much heat.” Nature is slow, Harrison says. “That’s how I saw so much—because I was out there all the time.”

Nature is slow, Harrison says. “That’s how I saw so much—because I was out there all the time.”My father and Harrison, who is now 73, are old friends. They met through the writer Philip Caputo, with whom my father served in Vietnam. My father, like Caputo and Harrison, is a keen bird hunter, and during my childhood the three of them would hunt woodcock and grouse near Grand Marais. A few times, Harrison came by our house for dinner, seeming less like a man to me than a force of nature with a Pancho Villa mustache.

“Jim Harrison is a writer with immortality in him.” Or so the London once wrote—a high-mileage blurb Harrison’s publishers have splashed across several of his books. Once I developed an interest in writing, I would sometimes stop and ponder my father’s Harrison collection. I noted the paperback jackets’ comparisons of Harrison to Melville, Hemingway, and Faulkner, but I was also aware of the Harrison Legend, which in the meantime has only grown: the films made from his work, the friendship with Jack Nicholson, the immense foreign readership, the incomprehensible appetite (he once ate a 37-course lunch and lived to write about it). There was also the way he wrestled with nature in his work. For Harrison, the natural world was not something to be cherished because it was pretty; rather, the natural world was something to be howled at, gloriously, in the night.

Imagine my puzzlement. The man who occasionally sat at our dining room table wrote stories set in the U.P., and critics in New York, London, and Paris regarded these stories as literature. Until that point in my life, I had heeded the inadvertent lessons of my English classes: literature was something written by the dead for the bored. Literature was decisively not about any towns I knew.

One day I pulled Harrison’s first novel, Wolf, from my father’s shelf. Subtitled “A False Memoir,” Wolf is about a Harrison stand-in named Swanson who retreats to Upper Michigan after youthful city living in an attempt to spot a wolf in the wild. I stopped at the line where Swanson says something about “the low pelvic mysteries of swamps.” I was 15, and for the first time in my life I underlined a phrase not to retain its information but to acknowledge its mystery.

I followed Wolf with Just Before Dark, a collection of Harrison’s nonfiction. I latched onto its first essay, which moves from an opening account of Harrison ice fishing on the bay in front of my father’s house to an anecdote involving dinner with Orson Welles. How was it possible, in life or in writing, to go from ice fishing in front of our house to dinner with Orson Welles?

The simple fact of Harrison’s existence demonstrated that you could slip from one world to the other, Escanaba to Orson Welles, smuggling literature both ways. Maybe it was time to thank him.

Harrison no longer lives in Michigan. Nine years ago he and his wife, Linda, sold their cabin in the Upper Peninsula and their farm in the Lower Peninsula and relocated to Livingston, Montana, for the summer and Patagonia, Arizona, for the winter. It was the early summer, so off to Montana I went.

STATES DO NOT get prettier than Montana. Driving across it is like being trapped in a beer commercial wrapped in the National Anthem. I was supposed to meet Harrison and Linda at the 2nd Street Bistro, Livingston’s best restaurant, at (for some reason) 6:07 p.m. I arrived at six and was seated at a table set with a hefty cheese-and-salami plate, around the edge of which WELCOME HOME JIM AND LINDA had been written in drizzled milk-chocolate script.

Harrison and Linda arrived at 6:07. “My son!” Harrison said. It was the first time I had seen him since 2006, at a party in New York City. At the time, he had been so afflicted with gout that he needed a cane to walk. Now Harrison’s cane was gone; his gout was mostly under control, as was his diabetes. His shingles, however, were dreadful, and he moved as deliberately as a cold-slowed bumblebee.

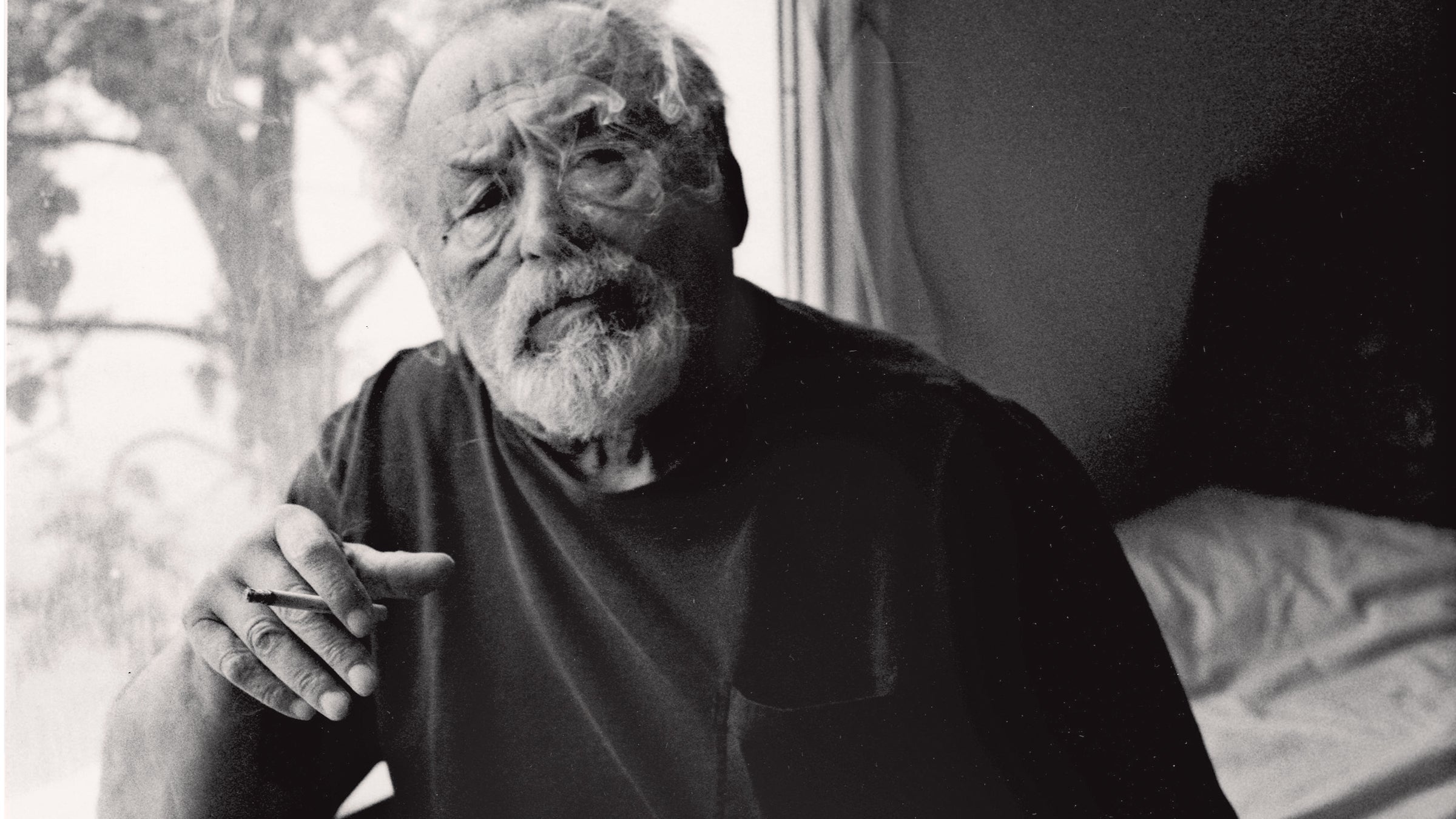

If you are describing Jim Harrison physically, you are pretty much forced to start with his eye. When he was seven a young girl, her motives unknown, pushed a broken glass bottle into his face, permanently blinding his left eye. When Harrison looks at you straight on, his left eye appears almost cartoonishly miscentered, as if he has taken a blow to the head and needs another, corrective blow to fix the problem. After six decades of double work, his right eye has weakened, as evidenced by a milky blue rim around the iris. But it is an amazing face, an iconic face, and Harrison’s goofy left eye is an essential, defining imperfection.

Everything else about Harrison seems big. His head looks as though it belongs on the end of something a Viking would use to knock down a medieval Danish gate. His body is big, too, but not fat. Rather, it seems full—the body of a skinny person that has been forcibly stuffed with food. Harrison’s face and hands are an identically bright blood-pressure red.

It was something of a relief when we finally took our seats. Linda, whom Harrison has described as “the least defenseless woman I’ve ever known,” sat beside me. She and Harrison have known each other since they were teenagers. One day Harrison spotted her climbing stairs in her riding pants and thought, I must have her. She was 15, he 17.

When I told Linda that I had last seen her when I was 12, she laughed, lightly, as though this were the most absurd thing she had ever heard. Harrison was studying the wine list. “Do you like wine?” he asked me, looking up. Harrison is a wine hound of international note, so this was a bit like being asked by Popeye if you like spinach. The first bottle came and, suddenly, another. I do not recall much of the night after the second bottle’s splendid arrival, and by the end of the evening I felt as though I had been beaten up by our meal. Harrison was in comparable shape. Outside, he hugged me—an act of affection that nearly triggered emesis. He asked if I was familiar with Chief Joseph’s famous dictum of dignified defeat. I nodded. “‘I will fight no more forever,’” I said grandly. Harrison smiled and said, with identical grandiosity, “I will eat no more forever.” Somehow I doubted that.

THIS FALL HARRISON will publish , his 17th work of fiction, and , his 14th book of poetry. A large number of these were written in the past 15 years, an unusual burst of late-career fecundity. When I asked him about this, Harrison explained that after a life of travel and carousing, all he did anymore was write and fish. “I’m trying to make my life smaller,” he said.

Harrison was born in Grayling, Michigan, in 1937. His mother was a homemaker and his father a government agriculturalist who worked with local farmers. He grew up in a close, warm family in what he “was slow to learn … was poverty,” as he writes in his memoir, Off to the Side. After his blinding, Harrison became a “berserk waif” whom Michigan could not hold. He lied about his age and found work as a bellhop at a series of resorts in the American West’s quadrilateral mountain states. He hitchhiked to New York City, where he lost his virginity to a sex worker. In Massachusetts, at 19, he met one of his early literary heroes, Jack Kerouac, who was impressively tanked. Eventually, Harrison returned home and completed a bachelor’s degree long delayed by hoboing at Michigan State, where his classmates included the novelists Thomas McGuane and Richard Ford. McGuane remains Harrison’s close friend: they have exchanged weekly letters for the past 45 years.

In 1962, when Harrison was 25, he delayed the start of his father and sister’s hunting trip by debating whether he should accompany them. In the end, he decided not to. Judith, Harrison’s younger sister, was the only member of his family who shared his obsession with art and literature; the day Harrison waved goodbye to her was the last time he saw her alive. A few hours later, a drunk driver plowed into his father’s car. There were no survivors. When I asked about these events, Harrison said that his father’s and sister’s deaths “cut the last cord that was holding me down.” Soon after their funeral, he wrote the first poem he was able to consider finished.

A few months later, Harrison was sent to Boston to stay with his brother, John, who was working at Harvard’s Widener Library. Through a chance connection, Harrison got some of his poems to the poetry consultant for the publisher W. W. Norton, which offered him a contract. The flap copy of that first 1965 collection, Plain Song, reads: “In his late twenties, Jim Harrison is a mature person and a poet who has found his own voice.” (When I read this aloud in Harrison’s presence, he disputed the factual basis of both statements.) “After graduating from Michigan State University, Mr. Harrison became a teaching assistant while he worked for his MA, but he abandoned the academic life because it was in conflict (for him) with the life of poetry.” (This was more accurate.)

The publication of Plain Song landed Harrison at SUNY Stony Brook on Long Island, where his colleagues included the literary critic Alfred Kazin and the young writer Philip Roth. “I wasn’t very long at Stony Brook,” he writes in Off to the Side, “when it occurred to me that the English department had all the charm of a streetfight where no one actually landed a punch.”

He returned to Michigan after being awarded an NEA grant in 1967 and a Guggenheim the following year, at which point he realized that the woods meant too much to him; he couldn’t go back to teaching. During Harrison’s otherwise liberating Guggenheim year, however, he literally fell off a cliff while hiking with his dog. The spill left him bedridden for months. At the urging of McGuane, he used this time to write Wolf. When he finished, Harrison, who did not have an agent, gave the only copy of his manuscript to his brother, who sent it to Simon and Schuster. But a postal strike stranded the manuscript somewhere between Michigan and New York City. Harrison assumed it would be lost forever. When the book finally made it to New York, Harrison was offered another contract.

Manuscripts of which a single copy exists? Postal strikes potentially derailing careers? Young novelists without agents being published by major American houses? These are antique emblems of a vanished world. Harrison is aware of this and refers to his literary ascendancy as “the old way.”

The literary world in which Harrison came up has now been tectonically ripped apart. How to navigate the adrift plates of this new terrain is not yet apparent—not to me, and not to most of the thirty- and fortysomething writers of my acquaintance. In this respect, visiting Harrison was not unlike climbing to the top of a mountain in search of a wise man. You want him to say the old way is still there because he is still there.

“NO MATTER HOW ACUTE,” Harrison has written, “the pain of hangovers can’t rise above farce.” This aperçu occurred to me while driving to Harrison’s home the morning after our meal. My farcical hangover was not helped by the potholed dirt road along which the Harrisons live. At least the view was spectacular. To my left: the Yellowstone River, swollen with snowmelt, and the snowcapped Gallatin Mountains, which looked like what a child might come up with if asked to draw mountains.

As I pulled into the driveway, the man himself emerged from the cabin he uses as a writing studio. “Look around!” he called over. “What don’t you see?”

“What?” I called back.

“Any other houses,” he said. He was wearing a fleece vest, unbelted pants, and rubber boots. With his cowlicky hair and potbelly, he looked a bit like a friendly garden gnome. When I complimented his view of the mountains, Harrison said, “They’re full of grizzly bears that will kill ��dz�.”

His dogs came running up: Mary, an elderly black cocker spaniel, and Zil, a squat-legged Labrador retriever with a stick clamped between her teeth. “Don’t throw her stick,” Harrison told me. “Under any circumstances. It will never end.” Harrison looked at Zil—wet and filthy from a recent dip in the Harrisons’ pond—and shook his head. “She’s such a fuckhead,” he said. “But she’s a free woman. I adore her.”

Linda came out after the dogs and regarded the thermal Patagonia shirt Harrison was wearing beneath his vest. It looked as though it had been recently used as a barmaid’s rag. “That shirt is filthy,” she said.

“I know,” Harrison said. “It must be washed. Eventually.”

Here the Harrisons started telling me about the rattlesnakes. At the dawn of creation, Montana received a generous helping of them. Until recently, an ungodly amount of the serpents considered the Harrisons’ property home turf. Linda admitted that she had long been terrified of snakes but no more: she had stabbed one to death the previous summer. In 2003, one rattler, startled by Harrison’s beloved English setter Rose, reared up and nailed the dog. Rose lived but was so neurologically damaged that Harrison had no choice but to put her down. This was war. On one sanguine afternoon, Harrison shot twenty rattlers. The creatures kept turning up until he hired a local snake guy to find their den, which was gassed. The snake guy filled two barrels with dead rattlers. The thing with rattlers, Harrison said, is this: you have to kill the alpha male. If the alpha male leaves the den and does not return, he will not be followed. Harrison smiled as though this had all sorts of other implications.

He took me inside the main house and showed me his business desk, where he pays his bills and signs his contracts and faxes his handwritten pages to his assistant in Michigan, who types up the work and faxes it back. “I can’t revise except in the type form,” Harrison told me. On the desk, I noticed, were five bottles of aspirin and a letter from Harrison’s French publisher. “Those people saved me financially,” Harrison said. Indeed, Harrison’s books sell in the hundreds of thousands in France, where he is known as the Mozart of the Plains. Over the years, he told me, he has met four or five dozen little French girls named Dalva, the titular heroine of what many regard as Harrison’s best novel. A French critic once told Harrison that his countrymen so adore his books because most American fiction is about “either the life of the mind or the life of action”; Harrison’s books were about both.

Harrison handed me a small steel mess kit, which a Frenchman gave him at a reading a few years ago before hurrying away. Harrison opened it. Inside were a hundred hand-tied trout flies. “This is weeks of work,” said Harrison, who spends a third of the year fishing the rivers around his home. “I’m trying to figure out how to find him and thank him.” He paused. “They don’t have very good fishing in France.”

By now Harrison was smoking. Harrison smokes so much that even when he is not smoking it still seems like he is smoking. As we headed out to his writing studio, he talked. Harrison talks unceasingly, about everything, in an endearingly permanent Midwestern accent that is a cross between Blackbeard the pirate, Fargo’s Marge Gunderson, and Harvey Fierstein. His mind is wonderfully crammed with experiences (“I ate a gross of oysters once, to see if I could. I could. I got gout the next morning”) and knowledge (“Certain bears eat 80 pounds of moths a day. Can you imagine?”).

The shades in Harrison’s cabin were pulled, and the wall above his desk was bare. He does not like distractions while he writes. Arranged with still-life exactitude upon his desk were some shotgun shells; a few feathers; a copy of Nabokov’s Ada (“A completely deranged book,” Harrison said approvingly); two Ziploc bags, one filled with bark from a Michigan birch tree, the other with sand from the shores of Lake Superior; three pairs of eyeglasses; and a Pompeiian amount of cigarette ash.

Around the room were photos of Anne Frank, Arthur Rimbaud, a woodcock, a polar bear, several of Harrison’s Indian friends, his deceased Zen teacher, the poet Gary Snyder, and his grandchildren. But I was most surprised to find a photo of Ernest Hemingway, the writer to whom Harrison has been most frequently compared. The New Yorker, for instance, once called Harrison “one of the more talented students of the école de Hemingway.” This is not a school the student ever willingly attended: Harrison once nastily described Hemingway’s work as a “woodstove that didn’t give off much heat.” He still resents the comparison, he told me, “because there’s no connection whatsoever” between his and Hemingway’s work. For what it’s worth, I agree with Harrison, whose large, ecstatic voice is more indebted to Joyce, Faulkner, Nabokov, and García Márquez. But Harrison writes of hunting and fishing and Michigan, as did Hemingway: for critics who neither hunt nor fish nor know Michigan from Minnesota, these are literary doppels that gänger. “In my lifetime,” Harrison told me, “the country has gone from being 25 percent urban and 75 percent rural to 75 percent urban and 25 percent rural.” A critic from a major American magazine once asked Harrison if he had ever personally known a Native American.

HARRISON HAS OUTLASTED those critics who initially wrote him off as a Hemingway-derived regionalist, and at times he has been as successful as a modern American writer can possibly be. For the first half of the 1970s, however, Harrison was trapped in that odd half-success of acclaim that lacks financial recompense. From 1970 to 1976, he made around $10,000 a year. Things got so bad that several people came to the Harrisons’ aid, including Jack Nicholson. (They met on the set of The Missouri Breaks, for which McGuane wrote the script.) Harrison’s financial troubles were considerably worsened by the fact that he did not file tax returns for half a decade.

Harrison’s unlikely solution to this penury was to write Legends of the Fall, a book of novellas. He wrote the title novella in nine days, basing large parts of the story on the journals of Linda’s grandfather. Legends is about a father and three sons whose fortunes wrathfully diverge around a woman. In 1977, Esquire published Legends in its 15,000-word entirety—an impossible thing to imagine today, assuming James Franco does not try his hand at novellas—and the movie rights were purchased. The Brad Pitt film didn’t appear until 1994, but Harrison was still paid handsomely. In 1978, he was stunned to realize that he made more money in the previous year than the president of General Motors.

This led to several years of what Harrison has described as a “long screenplay binge.” He is clear-sighted on what drove him into screenwriting (greed) and what kept him from succeeding more (he was not very good at it). Harrison’s Hollywood years had him lunching with a young Michael Ovitz and palling around with Warren Beatty. Sean Connery and Jack Nicholson had their first meeting at a lunch with Harrison. He did coke with George Harrison. Werner Herzog was so determined to convince Harrison to write the script for Fitzcarraldo that during a hotel-room negotiation, he followed Harrison into the shower.

This period strained his family life. Harrison has never shied away from discussing the years he spent chasing “actresses, waitresses,” as he recently admitted to The New York Times. Still, he and Linda have remained married for 51 years.

Harrison and Hollywood had a less perfect union. He attributes some of his irascibility to what he said were “the problems everybody had at the time. Cocaine, you know?” His literary friends, meanwhile, were as full of misbehavior as the loosest starlet. In the Key West, Florida, of the early 1980s, McGuane, Caputo, Harrison, and several other writers and artists often gathered to fish and destroy themselves. Harrison described for me a notably druggy Key West convocation, during which he was sticking a straw in “a big Bufferin bottle of great coke. We didn’t even bother doing lines.” When he returned home to Michigan, he could not remember his cat’s name.

“How many of your Key West friends didn’t make it?” I asked him.

“Quite a few,” he said. “I was thinking, though.” And here he paused. “That writer who hung himself—”

And here I had to pause, for I knew Harrison was thinking of David Foster Wallace. Ten years ago, I published an essay in a men’s magazine about my efforts to quit dipping tobacco. The story was greatly influenced by a couple of marathon conversations with Wallace, who shared the habit. When the essay was published, I was delighted to find that the issue contained an essay by Harrison called “How Men Pray.” Wallace wrote to me about my essay but also made time to compliment “Harrison’s prayer thing,” which he “really liked.” For a young writer, this was indescribable. Two of my literary heroes were talking to each other through me.

Shortly after Dave killed himself, I reread “How Men Pray,” and I remember wondering whether, in the midst of Dave’s torment, he might have found consoling Harrison’s belief that a writer is someone who “consciously or unconsciously takes a vow of obedience to awareness.” Perhaps he would have smiled at Harrison’s belief that the writer’s gift, and curse, is one of “excessive consciousness.”

Harrison brought up Jonathan Franzen’s much discussed New Yorker piece about Wallace, in which Franzen revealed that he could never get Wallace interested in his passion of bird watching. “This is interesting,” Harrison said. “Of the 12 or 13 suicides I’ve known, none of them had any interest in nature. In other words, they had no interest in what Rimbaud called ‘the other.’ The otherness, say, of nature.” They could not make, Harrison said, “that jump out of themselves.”

We were silent for a while. “You know,” Harrison said finally, “he loved his dogs for that last year, but he should’ve been having dogs for 30 years. Every day of the year, the first thing I do after breakfast is take the dogs for a walk. They absolutely depend on it. But it’s also what’s best for me.”

THE HERO OF HARRISON’S forthcoming novel, The Great Leader, is Simon Sunderson, a retired U.P. detective poking around the American southwest in search of a cult leader with a preference for underage girls. Other than Sunderson’s mid-book stoning by some fanatics, very little actually happens. It is a chase novel in which the chase never gets started. While The Great Leader is hugely enjoyable—Harrison is probably incapable of writing a novel that is not enjoyable—it is also slightly shambolic. Several of Harrison’s later novels have a similarly loose-limbed quality: gone is the piano-wire tautness of his earlier books. The language, though, remains stunning, like when Harrison describes U.P. winters as a “vast, dormant god” and describes some men “as a new kind of tooth decay in the mouth of the room.”

What The Great Leader is really about is divorce (Sunderson’s wife has recently left him), napping (a pastime in which Sunderson—like his creator—frequently engages), the appropriation of Native American religion (which is common among cults), and the curse of sexual persistence. Sunderson, Harrison told me, is “sort of in his last push, sexually. And that drives people a little bit crazy, that sense of waning sexuality. We don’t get so much work on what it’s like to be getting older.”

The singular pleasure of age, Harrison said, was “really not giving a shit.” Critics, for instance. “I don’t trust anybody that doesn’t do good work,” he said. “I don’t give them any credibility. If they can’t write, why should I believe anything they have to say?” Quite a few writers I know claim not to read their reviews; Harrison is the only one I believe.

I DROVE OUT to Harrison’s again the next morning. As I pulled into the driveway, I saw a tall redheaded bird high-stepping around. Inside the house I told Linda I was pretty sure I just saw a turkey. Linda was surprised and asked me to describe it. “That was a pheasant,” she said when I did. “You’re from Escanaba. Shouldn’t you know what a pheasant looks like?”

“Don’t tell Jim,” I said, adding, a moment later, “I’m joking.” She knew I was not joking. I had already confused a crow with a raven in Harrison’s presence. (Harrison: “Most writers know only four birds—hawk, gull, crow, robin.” I could not even fulfill this pathetic mandate!) I thought of one of my best writer friends, who once opened a magazine piece by making note of the “sugar pines” along a hill. I asked my friend how he knew what those trees were; such sensitivity to flora seemed unlike him. My friend told me he had no idea what a sugar pine was. He simply asked someone what kind of trees grew in the area. We both laughed.

The assumption of false authority is a useful writing trick, one I have used again and again, but maybe it’s also insidious. After all, it actually means something to know what things are called. You cannot share anything worth knowing unless you make it clear what you do not know. Harrison refuses to hide his research. If he reads a book to learn about something, the characters in his novels will invariably read the same book. It makes the stuff Harrison does know that much more striking.

Nature is slow, Harrison told me. “That’s how I saw so much—because I was out there all the time. When it’s slow you don’t, of course, always see something. You just see what’s there that day, and sometimes it’s quite extraordinary.”

It’s this patience that has allowed Harrison to write lines so lovely as this: “A creek is more powerful than despair.”

I met Harrison in his writing studio. On his desk was a letter he had begun writing to McGuane; he had gotten as far as “Dear Tom.” Harrison usually writes McGuane on Sunday and was planning to finish the letter before I arrived, but he had fallen asleep. When he woke up, he realized he wanted to tell me something, which was his dislike of “nifty gear” outdoorsmanship such as the kind he imagined was favored by the readers of ���ϳԹ���. He wanted to make sure I got that into the piece. He quickly had second thoughts, though. “Take that out,” he said, waving his hand. A moment later he said, “No, put it in; they need to hear it.”

SOMETIMES WHEN YOU are talking to Harrison, he gets incredibly still. He looks away and starts breathing wheezily from his chest and his eyes fade, and you begin to worry that he is in the middle of a cardiac event. Other times, when he is talking about drinking or writing or his wife or daughters or grandchildren, he becomes boyish, all the wrinkles ironed out of his face and his eyes slits of joy. Other times, when he is losing his patience, he resembles some kind of Indian werebear with a face wrecked by pit fighting. With Harrison it is impossible to feel something so simple as friendship. He seems to me the closest thing we have to a tribal elder. If writers ever required permission to raid another tribe and steal its corn, we would need to ask Harrison. He would listen carefully and judge prudently. We would never doubt his judgment, even when we saw him playing in the stream an hour later.

Harrison lives close to his mind. You sense this more and more the longer you stay with him. You want to know that unmediated part of him, and so you want to tell him things. I was not the only one. At one point in Livingston, during our drive-around, we ran into a young friend of his, who launched into a story about how he and his ex-girlfriend had recently decided to abort their child. But the younger man danced around mentioning this explicitly, forcing Harrison to say, “You mean you killed it?” His younger friend swallowed with a big-eyed blanch, and so did I. Later we met an aspiring screenwriter, who asked Harrison if he would have a look at one of his screenplays. “I couldn’t read a screenplay without puking,” Harrison said. Sometimes politeness was just a way to escape what needed to be said.

Before I left him, Harrison wanted to take me for a drive down the road, toward the foothills of the Rockies. “What are these hills here?” I asked, motioning out the window.

“What do you mean?”

“What are they called?”

“They don’t call ’em anything.”

How about those bushes? “Juniper,” he said, and pointed up along the hills’ escarpment. “See those rock formations? Full of rodentia. And rattlers.” We circled back to his house and saw, in quick succession, a yellow-rumped warbler and a western tanager, Harrison’s first of the season. A deer ran alongside the truck, and I asked Harrison why the deer in Montana looked different from the deer in Michigan. That was a mule deer, he said. Dumber, lower, mangier, and grayer than Michigan’s whitetails. We passed the big pink tree that grew next to his driveway’s entrance. What’s that called? “Ornamental crab apple,” he said.

We came back to the house, and Harrison wanted to know if I was going to continue teaching, which, I had told him the day before, was cannibalizing my writing time. Over the years, Harrison had been offered several “really cushy jobs” by various creative- writing departments. “And I said, ‘Why me?’ And they said, ‘We need some kind of name.’ However minimal.” But he always said no, thank you. “I turned one down for $75,000 in a year that we made $9,000.”

When I asked how he had been able to do that, Harrison told me what he told them: “‘Somebody’s got to stay outside,’ ” he said. “And I still think that’s true. Somebody’s got to stay outside.”

BEFORE LEAVING Montana, I decided to drive through Yellowstone Park. I was listening to conservative talk radio, the voices shrill and formless in my rental, beneath the mountain cathedrals. While Sean Hannity spent an hour rhetorically decapitating President Obama, I looked at the landscape, feeling the pressure between Americans and America, between body and being, between reality and aspiration. I wound up at Old Faithful, which Harrison said had been weakened in recent years; it might not even blow, he warned me. I wanted to see it blow. Maybe that would relieve the pressure. After an hour, it had not blown, and I had to catch a plane home. I knew by then I would be quitting my teaching job. It felt too good to be outside.