“The Hunter Gracchus” is a short story by Franz Kafka in which a dead body is trapped between life and death: each time he tries to cross the threshold into the unknown, he is yanked back to earth. In Joy Williams’s new novel, , the acclaimed writer plays with this concept of a death unachieved and expands it to address climate change—a phenomenon that is always coming for us, landing on our shores without ever doing us the courtesy of just finishing us off. Williams’s protagonist, a teenage girl named Khristen, is the inverted manifestation of Kafka’s hunter. Having died as an infant before being quickly revived, she distinguishes her situation from that of the Hunter Gracchus: “Gracchus’s death is incomplete,” she says. “In my situation, it is my birth.”

The specters of the dead-but-not-dead, the alive-but-not-alive haunt �Ჹ�����Ƿ�’s pages: in a time of climate emergency, Williams suggests, the state of the earth is pure purgatory. The apocalypse begins to seem preferable. As a record of our exhausted psychology in the midst of the climate crisis, Harrow is masterfully crafted. But when Williams takes on the topic of direct action, her approach is more disappointing.

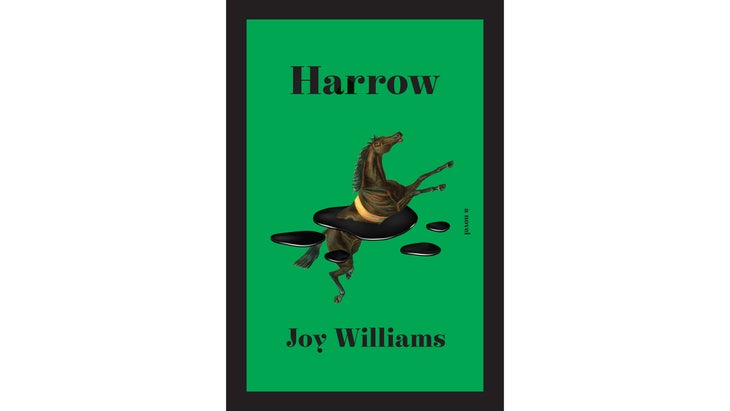

Williams, the author of five novels, five story collections, and two books of essays, is best known for her Pulitzer Prize–nominated novel, . She has a reputation as an experimental writer: long essays have been written on her sentences, which are broken and awkward, yet closer to life than the comfortable, easy legibility of most other fiction writers. The immediacy of her language complements her surreal plots and characters, which take inspiration from her Catholic upbringing in Massachusetts. The climate crisis is the perfect stage for a writer such as Williams, who is looking to rapture��all the time.

Khristen grows up in a near-future world falling apart: the smell of smoke is frequently in the air, nothing grows from the soil, and marine ecosystems have been destroyed. But she has her own problems to deal with. Khristen, like the leading ladies of many of Williams’s other works, is passive, almost blank. Despite Khristen’s quiet, unremarkable personality, her mother is convinced that Khristen’s brush with death must have granted her supernatural abilities. As the first third of the book takes us through the various calamities of Khristen’s life, we come to suspect that her true gift might be her ability to accept each blow leveled against her. Raised almost in isolation, she is abandoned by her father, who later dies. Then she is abandoned by her mother, who sends her off to a boarding school for gifted children. Like so many of the institutions Williams imagines in her fiction, the school presents like an anxiety dream: “There were no books, no paper. One was simply supposed to remember the gnomic things the instructors uttered.” Finally, in Khristen’s senior year, some kind of unspecified societal collapse takes place and she is forced to wander the desert without direction.

I had long yearned for a story of rage-fueled resistance, where perhaps for once the old could lead the young. But this is not that story.

Here we reach the part of the book I had been most looking forward to. The book’s jacket copy describes Khristen ending up among a group of old people with various plans to destroy polluting entities and punish the people behind them. Williams describes them as a “gabby seditious lot, in the worst of health but with kamikaze hearts, an army of the aged and ill, determined to refresh, through crackpot violence, a plundered earth.” I was excited to read this section, having grown tired of being surrounded by literature and movies that constantly tout young people as the last remaining hope to save the planet, while bemoaning the older generation’s inefficacy and sadness. I had long yearned for a story of rage-fueled resistance, where perhaps for once the old could lead the young. But this is not that story.

When Khristen arrives at a motel complex by a lake, called the Institute, where these supposed eco-warriors work in secret, it appears to be mostly abandoned. Lola, Khristen’s guide to this place, explains the situation to her: “The Institute’s winding down. Just the dotty ones are left or those whose abilities have greatly diminished…No one wants to leave anymore. They’re worrying about what comes next again.” Evidently, even in its heyday, the Institute hadn’t made much of an impact. Later, the Institute succeeds in persuading a couple more old folks to kill themselves for the cause. In this case, the mission is to blow up a factory. Williams, who seems to take a dark pleasure in poking fun at those who are stupid enough to think they could make a difference, taunts these characters in their last moments. The EMT who tends to the dying activists chastises them as their guts spill onto the asphalt: “What did you think they were making in that building you were so disapproving of?” he says. “Because I heard it was salad bowls. You’re not thinking big. Old people never think big.” The rest of these elderly activists get more or less the same treatment from Williams.

In Williams’s configuration there is no redemption in inaction or action. Those who go through with their missions end up being pathetic for thinking their sacrifice is worthwhile, while those who delay them are portrayed as being greedy, desperate to cling to the last shreds of life even as they lie dying with cancer.

It’s easy to walk away from Harrow believing that direct action—the last glimmer of hope after all other tools have failed—will prove to be useless, even if we engage with it at a larger scale. But there are activists who are punished to the full extent of the law for daring to be bold in their protest. Just recently, at Fairy Creek in Vancouver, Canada, where an Indigenous-led blockade aims to protect some of the world’s last old-growth forest from logging, and has targeted Black and Indigenous blockaders. There are others who pay with their lives for their resistance:��227 environmental protectors from around the world were killed in 2020 alone, the BBC . The consequences for resistance are so severe exactly because it is so threatening, yet every day we are made to believe that these are acts of relative insignificance.��

It is not an��author’s job to be morally or politically responsible, yet there are moments when it seems as if Williams understands what her own story lacks. In the scene where Khristen is asked by a ten-year-old judge to read Kafka’s “The Hunter Gracchus,” she gives her analysis of the story: “It was artificial, preposterous, inconclusive, a game of meanings that could not be won. It demanded its opposite, the other story, its foil, its righteous adversary.” If Williams is referring to Harrow through this critique, she is remarkably self-aware. Ultimately, the novel offers nothing that isn’t already imprinted in the hearts of those following the news: its message seems to be that we’re doomed, and there’s nothing we can do about it, except perhaps take ourselves out of the equation.

Maybe accepting the things we cannot change is the enlightened thing to do, but I look back on history and I wish the previous generations hadn’t abandoned us to deal with this crisis.��Williams’s words are for those on their deathbeds. Is it naive to think, Not yet?