Alaskan author knows wolves. He used to hunt and kill them during his 20 years living in remote Eskimo villages. Now, he's an advocate for the animals.

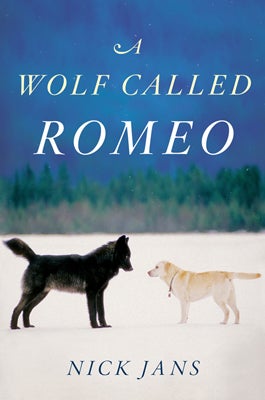

His latest book, , tells the unlikely true story of how a wild, black wolf befriended the people and dogs of Alaska’s capital city—living peacefully alongside its human and canine citizens for six years until it was killed by poachers from out of state. We recently caught up with Jans, a contributing editor for and a member of USA Today’s , to hear more about this unusual story.

OUTSIDE: In the opening scene, a wild wolf shows up in your backyard and starts playing with your dog. How did that go?

��������:��Well, that wolf might have well been a unicorn. He just appeared. It’s not like we don’t have wolves in the Juneau area. We do. But they come and go. But here’s this wolf trotting along like he was a dog. And, you know, I’d had 20 years of experience with wild wolves up in the . And, man, is it hard to see a wolf. But this guy just wasn’t worried about people. And he wasn’t sick; he wasn’t just some dufus of a wolf. He was obviously there for a reason. And the reason was our dogs. He wanted to interact with them. Really, I think he was the missing link to the whole story of the wolf that came to lie down by our fire, and became the genetically mutated soul of what we have lying at our feet today: Labrador retrievers, German shepherds, Chihuahuas. They’re 99.98 percent wolf. And that came from somewhere.

This wasn’t a lab, however. So what did you think when you first saw it?

First, it was, ‘Wow, there’s a wolf,’ and then, ‘Oh my god, he’s dead.’ Because I came out of Alaskan reality—and I don’t mean reality shows. I know that every wolf that allows himself to be seen, and is a little too casual, ends up dead. So I saw the entire story the first moment I saw him. And that’s not an exaggeration.

The people of Juneau had mixed feelings about having a wolf hanging around town, playing with their dogs. Why do you think some people enjoyed having the wolf nearby while others wanted it dead?

We have this schizophrenic relationship with wolves. Some people recoil and some people move toward them. I guess it's a natural fear, since it seems to be somewhere deep in our being—you know, the Big Bad Wolf, the Three Little Pigs, Peter and the Wolf, Dr. Zhivago. Wolves are bad news. That's the story we have in our heads. But what to do with a social wolf?

This was not the way it was supposed to go between big, wild things and us. Where you get to know an individual, and interact with them on a social level. Where it has no survival benefit for either party, but it's obviously enjoyable for everyone. I mean, he’d come over to see me once he knew me. And, I mean, I didn't feed him. And plenty of times, I went out without a dog, and he'd still come over to say hi. He clearly knew individuals. And it's hard not to call that friendship. I think most people would agree, we can be friends with a dog. But say, well, ‘The wolf was my friend.' People go, ‘Yeah, sure…’ Well, why not?

That's what this whole thing was about. The way we relate to the wild. Even people you'd think would know better believed this to be an impossible situation. We're talking about biologists, wildlife managers. They don't want that to happen. It's their worst nightmare. Because they want an animal to remain a faceless resource that can be managed—can be removed, can be shot, can have a radio collar put on, can be studied. They don't want people to be friends with individual wildlife.

You've hunted and killed wolves in the past. But then you took three years to write a book about this wolf. How did that happen?

I lived my entire adult life up until that point in the Brooks Range. Living in an Eskimo village. And I came up there to work for a big game guide, and I ended up traveling the country with some of the most gifted wolf hunters and trappers anywhere. Of course, I worshipped these guys. I had been brought up on . ‘How do you interact with wild animals?’ Well, you hunt them. Nobody told me any different. With time, I got pretty good at finding wolves, tracking them, and shooting them. By the time I moved to Juneau, because I met this cute gal who lived there who happened to be a card-carrying member of PETA, my hunting days were already fading in the rearview mirror. That was already a personal crossroads I had come to. I was just so full of dead stuff, I didn't know what it proved anymore. And I didn't want to do it. My only regret is it took me so long to figure that out. I wish I could have taken most of my bullets back.

It really seemed like this was the ghost of wolves past. And here I am, like Scrooge, and Marley's ghost follows me to Juneau—this black wolf that shows up at my door.

Not everyone in Juneau liked the fact that the wolf was called Romeo—even some of the people invested in protecting him. Why?

There is such a knee-jerk reaction among some wildlife managers against naming an animal. It creates individuality, and the line that I hear and I've heard before is: ‘It anthropomorphizes an animal. It creates an illusion of a relationship that doesn't exist.' I think that's old-school poppycock. If you go around Alaska, if you go to Anan Creek, the bears are named. Who named them? The Forest Service biologists who are there. If you go to Brooks Falls, the bears are named. Who named the bears? The National Park Service. If you go to McNeil River, the bears are named. Who named the bears? managers.

We're talking about the three major agencies: , , and the state all name animals at their own choosing, and they're given names that are pretty anthropomorphic—like Charlie Brown and Mrs. White. They're given names for a reason. And that's to recognize them as individuals. What's the difference if this wolf had been called 14-A6 or Romeo, or The Black Wolf? I don't think it would have made the least bit of difference. I sure as hell knew he was a wolf every second I saw him. And I looked at him every second like it was the last.

Do you think there will ever be another wolf like Romeo?

I think there was before. You know, in our human history, there must have been not one, but many. Again, the archetypal wolf that came to lie down by our fire. But, that said, I absolutely think this was a once-in-a-lifetime experience. And I think it was the wildlife experience of my life. And that comes having met and having seen tens of thousands, maybe hundreds of thousands of caribou, I don't know how many moose. Hell, I've seen three-dozen bears up close this fall alone. And this wolf— getting to know this wolf as an individual, and him knowing me, and him knowing other people—it was really this transformative experience, and it transforms you permanently. You start looking at everything in a more personal way.