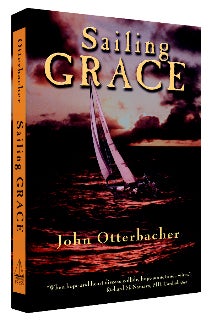

Heart disease may have run in 's family, but he was determined not to let that stop him from fully living his life. And that meant testing his limits, whether by running marathons or sailing across the Atlantic four times after getting a heart transplant. For more on his nautical adventure, check out his biography, (Samadhi Press). He shared some thoughts with , below.

–Aileen Torres

You and your family lived on your boat, Grace, for about five years. What made you decide to stay on the boat for so long after your initial sail to Ireland?

Getting back to Michigan would have taken a year, using the standard seasonal routes down the coast of Europe and Africa, across to the Caribbean, up the East Coast of the U.S., up the Hudson River, and through the Erie Canal and Great Lakes. More importantly, we were just having a great family adventure–one of those instances when the reality outshines the dream. We wanted to sail the Irish, North, Baltic, Mediterranean, and Caribbean seas, to immerse ourselves in the beauty and history of Europe, North Africa, the Mediterranean, and Caribbean. Time with my wife and the kids was paramount, given the uncertainty of my health. I hoped to show the kids the joy of exploration, embracing the unknown, developing that radical attention that fresh environs summon up.

What were the most difficult moments, physically and nautically, during your voyages?

The more subtle danger out there is the incremental weariness that can lead to a fatal mistake, and, in my case, the deep chill during heavy weather that causes an ache in my damaged heart. That I could never be entirely sure of my own limits made it very interesting.

What were the best moments?

Many adrenaline-infused moments in an unforgiving storm–equal parts beauty and terror. At the other end of the continuum, landfalls in places like Dunkirk, Horta, Den Helder, Schull Harbor, Gibraltar, Casablanca, Antigua–the pure pleasure of slipping off your foul-weather gear at the end of a long passage and the profound satisfaction of knowing you have transcended your familiar limits.

How is your health these days?

In short form, I have a damaged heart and a spectacular life. I will probably not suit up as a defensive back for Notre Dame. And competing in the 100-yard dash at the next Olympics is probably out. My heart issues have given me the great gifts of both knowing with some degree of probability how I will die and robbing me of the illusion of longevity. And though I cherish longevity–and plan to live just as long as possible–I no longer wrap myself in the false sense of security that allows me to waste the time I have. The real issue is how I choose to live the life I have.