Late last Friday, ║┌┴¤│ď╣¤═° obtained an advance copy of the Central Asia InstituteÔÇÖs annual Journey of Hope newsletter from Anne Beyersdorfer, the independent public relations specialist who has, for the past three weeks, acted as the organization's temporary director. On April 17, a report on CBSÔÇÖs 60 Minutes, followed by Jon Krakauer with his expos├ę Three Cups of Deceit, leveled charges of fraud and fabrication against Mortenson, alleging the Bozeman, MontanaÔÇôbased philanthropist misappropriated funds, lied about the events of his bestselling books Three Cups of Tea and Stones Into Schools, and made up the story of his 1996 kidnapping in Waziristan at the hands of a so-called ÔÇťemerging Taliban commander.ÔÇŁ

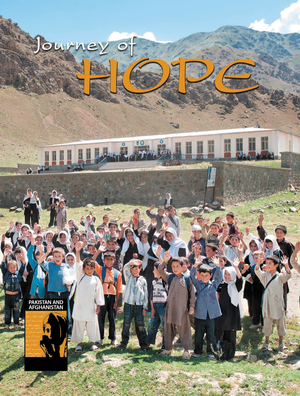

For supporters, who have been anxiously awaiting an official response from Mortenson and CAI, the 14-page Journey of Hope newsletter serves as a broad outline of CAIÔÇÖs defense rather than a blow-by-blow rebuttal of every allegation. In a normal year Journey of Hope, which is usually released in November, serves as an annual report for the organizationÔÇÖs most fervent supporters. WhatÔÇÖs surprising about this special edition is its general lack of urgency.

Neither 60 Minutes nor Krakauer are ever mentioned, and the first reference to the ÔÇťrecent media reportsÔÇŁ doesnÔÇÖt appear until the sixth paragraph of the opening note from board chairman Abdul Jabbar, who flatly denies any wrongdoing: ÔÇťThere has been absolutely no financial misappropriation.ÔÇŁ His note is followed by another three stories that lay out an aggressive and expansionary plan for CAI, including a ÔÇťfemale teacherÔÇÖs training collegeÔÇŁ in Kashmir, ÔÇť60 new schools across Afghanistan in 2011,ÔÇŁ and ÔÇťthree schools in remote southeastern Tajikastan,ÔÇŁ a country that the charity has not previously operated in.

As for the defense, it begins on page ten and takes the form of an FAQ. It starts off strong. In Deceit, Krakauer accuses CAI of spending only 41 percent of its budget building schools and of reporting ÔÇťthe millions of dollars it spends on book advertising and chartered jets as ÔÇśprogram expenses.ÔÇÖÔÇŁ Central to KrakauerÔÇÖs criticism is the notion that ÔÇťDomestic outreach and education, lectures and guest appearances across the United StatesÔÇŁ shouldnÔÇÖt count as programs but fundraising and promotional overhead. CAIÔÇÖs mission, after all, is building schools for girls.

On this count, CAI offers a convincing defense, noting that its 1996 certificate of incorporation spelled out a dual mission:╠ř ÔÇť[T]o establish and support education in remote mountain communities of Central Asia and to educate the public about the importance of these educational activities.ÔÇŁ (Its current mission statement, though different, could arguably mean the same thing: ÔÇťTo promote and support community based education, especially for girls…ÔÇŁ)

CAIÔÇÖs position is that its outreach is every bit as important as building schools and that MortensonÔÇÖs talks and his resulting travel expenses are a crucial part of its mission. If you buy this argument, and many supporters do, the percentage of its spending on programs is above 75 percent, putting it on par the industryÔÇÖs best practices. On this count, the newsletter also hints at a possible legal defense: ÔÇť[MortensonÔÇÖs] presentations and his books help fulfil the stated corporate and charitable purposes of CAI.ÔÇŁ

The charityÔÇÖs explanation for KrakauerÔÇÖs so-called ÔÇťghost schoolsÔÇŁ also seems reasonable, if you believe that Afghanistan, and the areas of Pakistan where the charity operates, are difficult places to maintain security let alone accountability. CAI chalks up lapses in oversight to in-country project managers and, in at least one case, to a disgruntled employee who conned the organization into believing heÔÇÖd been building schools, when in fact heÔÇÖd been embezzling.

ÔÇťI trusted him and loved him like a brother,ÔÇŁ says Mortenson in the report. ÔÇťUnfortunately, for the first time in our history, CAI wound up on the short end of the stick.ÔÇŁ

The organization also points out that ÔÇťmany schools in the remote, mountainous areas close for two months or longer in the winter,ÔÇŁ which could explain why visits by 60 Minutes appeared to show that some schools were no longer operating.

But while the report openly addresses critiques of CAIs spending and on-the-ground effectiveness, explanations for MortensonÔÇÖs alleged financial improprieties and fabricated stories are conspicuously absent. There is no mention, for example, of the millions of dollars CAI spent on advertising to promote Three Cups of Tea and Stones Into Schools, the proceeds of which, the organization acknowledges, are ÔÇť[MoretensonÔÇÖs] alone.ÔÇŁ Nor do they address KrakauerÔÇÖs accusation that a school in AfghanistanÔÇÖs Wakhan Corridor was rushed to completion in order to meet a publishing deadline for Stones Into Schools. During the 60 Minutes report, Steve Kroft points out that CAI has released only one audited financial report in 14 years, a disturbingly low number for a non-profit of its size and stature. In the FAQ format, CAIÔÇÖs response appears intentionally╠ř misleading:

Q: ÔÇťEvery nonprofit must file an annual tax return. According to reports, your nonprofit only filed once in 14 years – is that true?ÔÇŁ

A: ÔÇťNo. IRS 990 forms filed for every year since CAIÔÇÖs inception are available on our website,

While those forms are indeed available, tax returns and audited financial statements are not the same thing. And ║┌┴¤│ď╣¤═° couldnÔÇÖt find any reports that accused CAI of failing to file a tax return.

As for the allegations that major parts of Three Cups of Tea were fabricated, the newsletter offers only boilerplate: ÔÇťThe contents of Greg MortensonÔÇÖs books Three Cups of Tea and Stones Into Schools are based on events that actually happened.ÔÇŁ Given how much latitude for dramatic license that statement offers, it can hardly be the reassurance that fans of the book had been hoping for. Still, CAI is sticking to the story that Mortenson actually did visit Korphe, the site of his first school, in 1993ÔÇöa claim that ║┌┴¤│ď╣¤═° is plausible. He also maintains that he was, in fact ÔÇťdetained and held against his willÔÇŁ in Waziristan, in 1996.

Mortenson is quoted frequently throughout the newsletter, but his byline appears only on the last page in ÔÇťA Message to the Children.ÔÇŁ In his note he calls the allegations against him ÔÇťmean spiritedÔÇŁ and apologizes ÔÇťif these attacks left you feeling confused, hurt, upset, or disheartened.ÔÇŁ

For supporters who were hoping for a more direct response from CAIÔÇÖs founder, board chairman Jabbar offers that Mortenson will do a series of longer interviews ÔÇťafter his impending [heart] surgery,ÔÇŁ which is scheduled for sometime in May.

You can download the full report here (, or go to CAI's to read it online.

–Christopher Keyes () and Grayson Schaffer ()

╠ř