“AMERICANS LIKE TO WESTER; but when you reach the Pacific, why stop there?” wonders Ian Frazier in Travels in Siberia (Farrar, Straus & Giroux, $30). Twenty years ago, contributing editor Frazier went westering in his classic Great Plains, and now he’s hopped the Pacific to wander across another mythic, yawning land: Siberia. In size, the place makes America’s Great Plains look like a bath mat. The continental United States plus most of Europe could fit inside it. The largest forest in the world, the Russian taiga, runs across its middle for 4,600 miles. And yet what we know of Siberia, mostly, is one word: exile. Czars and Soviet apparatchiks sent millions to prison camps there. All suffered; many never returned. Frazier wants to get to know the land behind the infamy. “Using a place as punishment may or may not be fair to the people who are punished there,” he writes, “but it always demeans and does a disservice to the place.”

Ian Frazier

Travels in Siberia by Ian Frazier

Travels in Siberia by Ian FrazierIn the case of Siberia, though … not so much. On the evidence presented here, the place is pretty awful. Travels incorporates five Siberian journeys between 1993 and 2009, but the meat of the book concerns Frazier’s six-week drive across the region in 2001. Accompanied by two spectacularly indifferent Russian guides, he drives east from St. Petersburg in a crappy van filled with anxiety and hope. Hope mostly fails him. Frazier and his mates squelch a van fire, hunt for campsites free of knee-deep trash, and vomit in a town named Unhappyville.

Because it’s Frazier at the wheel, though, his misery is a reader’s delight. Here he is on Siberia’s armies of mosquitoes: “On calm and sultry evenings as we busied ourselves around the camp, mosquitoes came at us as if shot from a fire hose.” He also catches quiet moments of beauty amid the overwhelming bleakness, finding, for example, meaning in the ubiquity of crows, which “seem to be awaiting the return of Genghis Khan,” so they can feast on the casualties of war. For all its misery, Russia enchants Frazier with what he calls its “incomplete grandiosity,” its operatic way of encompassing the heights (Tolstoy) and depths (Stalin) of humanity, a grandiosity that doesn’t end but rather “just trails off into the country’s expanses,” always heading east, into Siberia.

Reading Giants

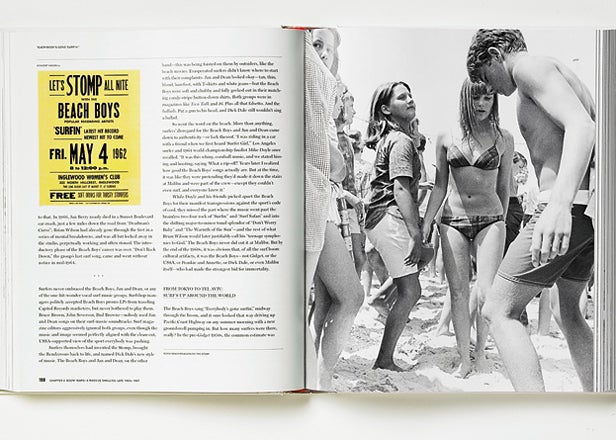

A comprehensive history of surfing.

Meticulously researched, smartly written, beautifully laid out. Also very, very heavy. At 496 large-format pages, Matt Warshaw’s The History of Surfing (Chronicle Books, $50) is a coffee-table crusher. But it’s not dense. Warshaw, the last word on wave-riding trivia since his Encyclopedia of Surfing was published in 2003, has a knack for entertaining by way of detail. For him, it’s the lesser-known moments that shine the brightest: surfing’s “grand patriarch,” Duke Kahanamoku, escaping his money problems on a sojourn in Australia; the rowdy, pre–Endless Summer surf-film screenings, where “firecrackers were lit and rolled across the floor.” Mining for such tales demands an obsessive spirit and lots of time. (Warshaw was three years late with his manuscript.) For modern surfers with only a hazy sense of their heritage (i.e., most of them), the result is required reading. Just lifting the thing builds strength for those longer paddle-outs.

Overboard

A history of old-time adventurer Joshua Slocum.

Sailing

The Hard Way Around: The Passages of Joshua Slocum by Geoffrey Wolff

The Hard Way Around: The Passages of Joshua Slocum by Geoffrey WolffBy age 21, Joshua Slocum, a Canadian bootmaker’s son, had sailed around the world twice and nearly died as many times. Then, says Geoffrey Wolff in The Hard Way Around: The Passages of Joshua Slocum (Knopf, $26), things got interesting: He became a pioneering cod fisherman; married twice; raised four children at sea and lost three more to disease; fended off three mutinies; killed one of those mutineers; and circumnavigated the globe alone from 1895–1898. His understated account, 1900’s Sailing Alone Around the World, remains an adventure-lit classic. But Wolff’s book, written in muscular, academic prose, fills in the gaps on either end of that epic, both savory (Slocum was hopelessly devoted to his first wife, Virginia, who died young) and not (he was falsely accused of rape late in life). Wolff does no theorizing about the cause of Slocum’s mysterious death, which occurred sometime between 1908, when he set off for the Amazon, and 1924, when the world press finally acknowledged his mortality. Instead, Wolff focuses on the legend at the peak of his powers, portraying Slocum as an underappreciated writer and (mostly) honorable man who fought to uphold a craft threatened by the rise of steamships—not because he chose to but because he had no choice. “A genius at navigation, dead reckoning, calculating lunar tables, and surviving tempests,” Wolff writes, “he was frequently lost on land.”