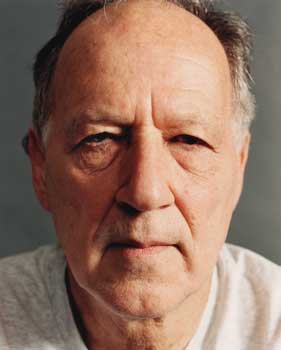

Who can forget that scene? In Grizzly Man, with his back to the camera and large headphones on, German director Werner Herzog listens to an audio recording of bear fanatic Timothy Treadwell and his girlfriend, Amie Huguenard, being eaten by grizzlies. Afterward, Herzog turns to the friend of Treadwell’s who owns the tape and, in his distinct Teutonic accent, tells her to destroy it. Herzog, 68, is known for his extreme filmmaking in radical locations: he dragged a massive steamship over an isthmus in Peru for 1982’s Fitzcarraldo and spent 44 days in Thailand’s jungles for 2006’s Rescue Dawn. He often examines the complicated line between humans and nature, as in the Oscar-nominated Antarctica documentary Encounters at the End of the World (2007) and his newest, Cave of Forgotten Dreams. The latter required unprecedented permission from the French government to shoot inside the Chauvet Cave in southern France, which contains the earliest known prehistoric art, dating back an estimated 32,000 years. The cave is a perfect canvas for Herzog’s 3-D cameras, which surreally bring to life remarkable drawings by Stone Age artists. Mountainfilm in Telluride festival director David Holbrooke caught up with Herzog, who was at home in Los Angeles.

HOLBROOKE: You must have felt fortunate to go into a place like the Chauvet Cave.

HERZOG: Yes, because the French are very territorial. I was able to go in because I’ve had a very long interest in caves. I was 12 when I saw a book about the [nearby] Lascaux caves, and they knew I was serious about the subject.

It must’ve been extraordinary.

It was. But I was focused on getting great pictures. I was allowed only one week of filming, four hours a day. I was only allowed to have three people with me. And I could never step off the very narrow walkways. Other caves—Lascaux, for instance—have been destroyed by people. There is a fungus there now, and they can’t let people in if they want to save the wall paintings.

Weren’t there issues with poisonous gas in Chauvet?

In one branch of the cave, there were high levels of carbon dioxide; in other sections, a very high concentration of radon. So you could stay only for short periods before you started feeling woozy.

Why did you do this in 3-D?

I’m not a great advocate of 3-D in cinema. It’s OK for films like Avatar with the big fireworks. Otherwise, certain things do not really function well in 3-D. I was a skeptic, but the moment I saw the cave for the first time, without any camera, it was immediately clear that all these dramatic bulges and formations and undulations and niches would show up better in 3-D. And they were actually utilized by the artists. It was part of their canvas. A bulge would be the bulging neck of a bison. From a niche, a horse would carefully step out. There were whole stories, whole dramas.

Would you work in 3-D again?

It was imperative in this case. But I’m now doing a film on death-row inmates in Texas and Florida. And that, of course, is not going to be in 3-D.

You’ve been described as fearless. Are you?

No. I’m afraid of spiders.

How hard was the decision as a director not to play the audio of Treadwell’s death in Grizzly Man?

It was instantly clear this must never be published. There is such a thing as privacy and dignity in death. It was just horrifying, and you have to brace yourself to experience something like this.

That line between humans and nature is something you’ve examined a lot. In Grizzly Man, you say, “I believe the common denominator of the universe is not harmony but chaos, hostility, and murder.”

What I’m trying to say in the film, through Treadwell, is about this New Age romanticization of wild nature. I have an ongoing argument, and it’s an obviously different position. When you look out at the universe at night and you look at the stars, you know that there is a huge mess out there, and it’s very hostile and very inhospitable. There is no such thing as the harmony of the earth. I’m not buying this New Age crap.

You run the Rogue Film School, which teaches “lock picking” and “the exhilaration of being shot at unsuccessfully.” Do you need all this to be a good filmmaker?

It’s not a film school that teaches you how to use a camera, or how to shoot film, or how to record sound. It’s something different. Wilder. If you’re working within the studio system, you don’t need that. But if you’re aiming at something else, yes, you need certain things that are basic.

Are there any films that you’ve wanted to make but haven’t been able to? Wasn’t there a plan to make a documentary about K2?

It was a plan for a feature. I made the documentary as a test run, to see if it is possible to shoot a feature film up there. The answer after a few days was immediately clear: No. You just don’t do a feature film on K2. Period. End of story.

Any filmmakers you like?

Jean Rouch, the French filmmaker, who made the mid-fifties film Les Maîtres Fous—The Mad Masters—one of the truly great films.

Are there any filmmakers out there today worth paying attention to?

No.