In 1991, a development company set out to build a high-elevation, year-round ski resort on a remote glacier in British Columbia’s Purcell Mountains. The company’s plans promised over 5,600 vertical feet and 20-plus lifts accessing four mega glaciers at what they called .��

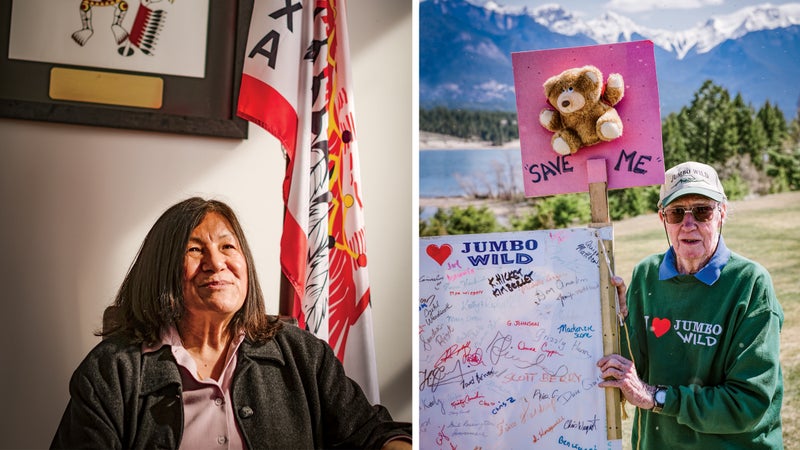

Many have been fighting the development for decades. Local residents want to see their backyard kept wild, the Ktunaxa First Nation��believes the land is sacred and shouldn’t be built upon, and scientists and environmentalists say the region is a major wildlife corridor and a development could jeopardize habitat for grizzly bears and other animals. Although the opposition had a major triumph this summer when the local government denied the project’s environmental assessment certificate, the developers say the resort is still a go, albeit with an altered construction plan that won’t require an environmental assessment. They hope to resume construction within the next couple of years.��

A new Patagonia-funded film called , premiering in October, aims to give voice to people on both sides of the debate. We spoke to the film’s producer, Nick Waggoner of Sweetgrass Productions,��about how the project came together and what skiers stand to gain—or lose—if the resort gets built.

OUTSIDE:��There are a lot of mountain development projects in the works. Why did Patagonia want to get involved with this one?

WAGGONER: I got a call from Patagonia and they said, ‘We want to make a film about land use and skiing. We want to make a documentary about an issue that local people are passionate about, that we can help raise awareness about.’ I knew the Jumbo Glacier issue well, and it felt like serendipity that they were approaching us to make a film we were already interested in making. This kind of environmental activism is deep in Patagonia’s DNA. When you look at Jumbo, it’s about wildlife corridors and wilderness that’s disappearing; it’s about how we engage democracy and how we protest when democracy isn’t working. The mountains around Jumbo are some of the most stunning peaks I’ve ever seen. This project is about activating people to protect the mountains in their backyard.��

“Any normal person would have given up long ago—on both sides.”

The government rejected the resort’s environmental assessment this summer. What does that mean for the development?��

This is the first time the government has said no Jumbo Glacier Resort, so it’s definitely a pivotal point. At first it seemed like a nail in the coffin, and, maybe it is, but there’s still potential for this resort to move forward. Right now, JGR has downsized their plans to build a 2,000-bed ski resort, which is just under the threshold that needs an environmental assessment certificate. Basically, they are trying to navigate around this latest decision.

What was the reaction on both sides to the development’s most recent roadblock?

Champagne, tears, frustration. Some of the phone calls we recorded were unbelievable. It was emotional on both sides. It was emotional as filmmakers. We had already become friends with people on both sides of the issue, and so it was very powerful feeling the weight of 24 years. Imagine if you had worked the better part of your life fighting for something you believed so deeply in. How would you feel? I suppose the rest will reveal itself in the film.

This development has been over two decades in the process. Why do a film on it now?

This process has been going on for 24 years, and we just happened to be in the right spot when the most critical decision was made. This summer, we were at the celebrations, and we were there when tears were shed in frustration. People have dedicated massive pieces of their lives to this issue. As we started to make this film, the government was about to make a decision, and then it got delayed, but there was a sense that this might be the decisive year. But, then again, I think every one of the 24 years has likely seemed that way for all involved.��

Jumbo Glacier Resort, if it happens, would have a peak elevation of over 11,200 feet. Pretty smart for a ski area in the midst of warming winters to position itself so high, don’t you think?

It’s very high by Canadian standards. When developer Oberto Oberti started on Jumbo, he did a study of the entire continent to determine the number one location for a ski resort in North America. Based on elevation, snowfall, and duration of the winter season, he concluded that the western side of the Columbia River Valley in British Columbia was it. The skiing in Jumbo is like the Alps but with more consistent snow. The proponents would argue that once skiing is gone elsewhere, Jumbo will still hold cold, alpine snow, and I can’t say I disagree with them.��

“The skiing in Jumbo is like the Alps but with more consistent snow. The proponents would argue that once skiing is gone elsewhere, Jumbo will still hold cold, alpine snow, and I can’t say I disagree with them.”

The opposition to the development is deep. What’s your take on the developer’s side of things?��

I think the developers have been horribly wronged by the process. For 24 years, the government had given them an unbelievable number of hoops to jump through, and, every time they successfully do, there’s another hoop. The developers are quick to shoot holes in the arguments, claiming the politicizing of science, false spiritual claims that are a result of bad tribal politics, and also pointing to overly idealistic hippies who need to reconcile their needs for services like health and education with an economy healthy enough to generate the tax revenue needed to provide them.��

Canada’s First Nations tribe considers this land sacred. Are the Purcells sacred to you?

In the sense of how I connect to a place that feels wild, a place that helps me to understand that I’m part of that wild system, yes, it is sacred to me. Pictures can’t do it justice, and film can try, but you will never understand the power of Jumbo until you’ve walked beneath its peaks and watched the full moon rise over its glaciers. The scale is immense, the consequences severe. One of my favorite quotes in the film is from Joe Pierre, a Ktunaxa storyteller. He says, ‘You wouldn’t want to build a resort in the Vatican, so why are we talking about building a resort in any other sacred space?’ It’s an important point about our cultural context.

What message do you want viewers of the film to walk away with?

I want people to get outside, and I want people to develop a deeper connection to the land in their backyards. That’s been a thread through all our films, but particularly with Jumbo. This is not an isolated conflict of land use and, as one of the characters in the film so perfectly says, ‘You can’t run from these kinds of issues. Because one day they’re going to come knocking and you’re going to have to make your voice heard.’

��

Clarification: This article has been updated with the full name of the First Nation who is protesting the resort.