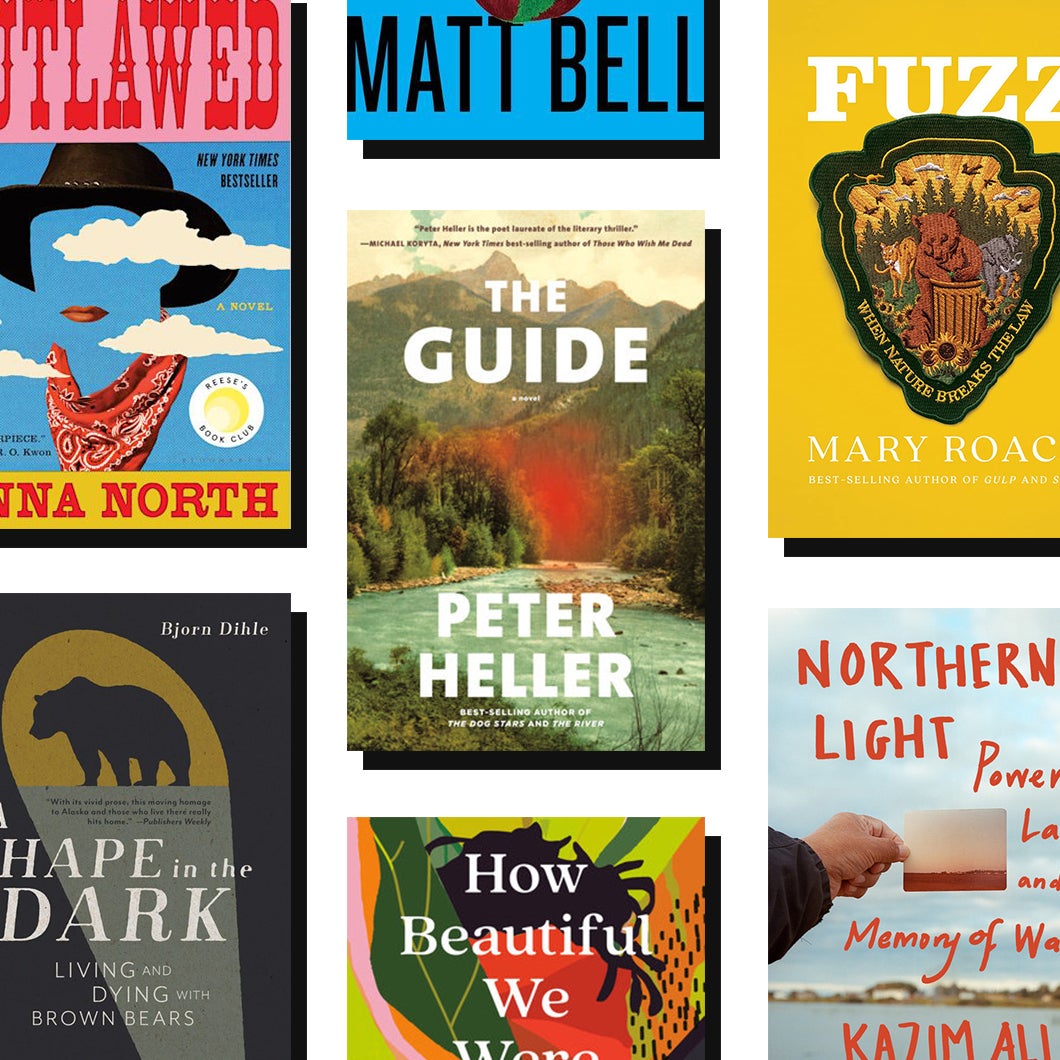

The past year was a great one for reading at ���ϳԹ���: in addition to relaunching our book club this fall, we spent our spare time digging into an especially strong crop of fiction and nonfiction about the outdoors. There were imaginative works of climate fiction, thoughtful memoirs by new and established authors, thrilling adventure tales, and even a book that made us feel a little less hopeless about our warming planet. Here, ���ܳٲ��������contributors look back on some of their favorite books of 2021.

How Beautiful We Were, by Imbolo Mbue

In Imbolo Mbue’s second novel, the determined heroine, Thula, leads an uprising against an oil company that has poisoned and mistreated her fictional African village, Kosawa, for decades. The book begins in the 1960s and then trades perspectives among Thula’s family members and a collective chorus of her schoolmates to tell the story of the next 40 years of struggle. With its lack of geographic and historical references, and its often nameless villains (The Leader, The Sick One), the novel reads something like a fable. But there is no tidy moral to this tale, and in fact Mbue does not seem at all interested in being didactic. seems most of all to be a study in how people respond to injustice and how the fight against it endures. Each character brings their own opinion of how violently or radically they should take action, whether they should leave the village altogether, and how they could ever be properly compensated for their suffering. Through each person’s eyes, Mbue clearly elucidates the real-life geopolitics and colonial history that propel the abuses of extractive industries. —Erin Berger

�������������,��by Matt Bell

In the 18th century—the early years of the conquest of North American forests—a faun and his human brother sow what’s now Ohio with apple seeds. In the near future, most of the United States (human, animal, vegetable) has been wiped out by a massive dust bowl or , and one biotech firm positions itself as the key to human survival. And in the distant future, a genetically engineered human hybrid scours the land—now in the grip of a new ice age—for signs of life. These are the three strands that comprise Matt Bell’s ambitious, capacious novel . To say what knots them together would be a spoiler, but suffice it to say, the novel is a loose retelling of the myth of Orpheus and Eurydice that’s also about climate change, colonialism, American exceptionalism, and the limits of private industry. —Katherine Cusumano

Northern Light: Power, Land, and the Memory of Water, by Kazim Ali

Kazim Ali’s family came from India and Pakistan, but he lived on Canada’s Pimicikamak Cree Nation as a boy. His father helped design the Jenpeg hydroelectric dam, which provides power across Manitoba, but it also flooded the ancestral lands central to the tribe’s identity. That loss destabilized the community for the next 40 years, spurring the highest suicide rate in Canada. In 2014, the tribe occupied and protested the dam, and Ali returned to document their fight. In , he braids that narrative with his own, grappling with his family’s legacy as both victims and perpetrators of stolen land. On every page, he tries to decipher what it means to be “from” a place, crafting a poetic exploration of home, assimilation, and belonging. —Rose Hansen

I Love You but I’ve Chosen Darkness, by Claire Vaye Watkins

Claire Vaye Watkins isn’t coy about packing her novel with so many autobiographical details that it almost seems like a memoir. The main character’s name is, uh, Claire Vaye Watkins. But that’s the least interesting aspect of this book, which is as much a journey into the narrator’s id as it is an excavation of personal and family history. The fictionalized Watkins, who’s experiencing postpartum depression and reevaluating her marriage and life, heads off to Reno, Nevada, on a work trip and may or may not ever return. Throughout, Watkins also describes (in at least partly fictionalized terms) her childhood in the desert; her brilliant mother, who struggled with substance abuse; and her father, who was part of the Manson family. is a love letter to the landscapes and weirdos of the West, and it’s an honest struggle to understand motherhood, how the people we love shape us, and how we find a sense of home, with no need for easy answers. As Watkins writes early on, “Books heal people all the time, just not usually the people who write them.” —E.B.

Under the Sky We Make, by Kimberly Nicholas

Nonfiction books about climate change tend to fall into two broad categories: overly sciencey snoozers or hope- and change-filled dross that don’t actually address the issues. In , Kimberly Nicholas, a climate scientist with a funny, empathetic writing voice, transcends both of those tropes. She delivers a book about the grim reality of facing global warming that is clear, science-based, and realistic without being fatalistic. By making herself a character in the narrative and bookending the science with stories of the emotional toll of living in an escalating crisis, Nicholas makes the climate research she writes about feel vivid and wrenching. Under the Sky We Make is informative and easy to read, but, most important, it outlines specific, actionable ideas—both personal and structural—about how to slow the world’s demise into a burning fireball of death. I’m not going to say it gave me hope, but it definitely made me feel less helpless. —Heather Hansman

The Guide, by Peter Heller

In this novel, billionaires seek solace at the luxurious Kingfisher Lodge in Colorado, and so does the poetry-loving cowboy, Jack. Still grieving the deaths of his mother and best friend, he is simply after a bit of peace in his new job as a fishing guide for the rich and famous. But there’s trouble in paradise: trigger-happy neighbors, screams in the night, guest behavior that seems questionable. And in the greater world, a global pandemic still looms. wants to be a page-turning thriller, but the writing is too lyrical to rip through. That’s no surprise—Heller was a poet before he began writing fiction. While you’ll read him for the plot, you’ll love him for the language. His fishing scenes are so beautifully crafted that they alone justify picking up this book. —R.H.

The Secret to Superhuman Strength, by Alison Bechdel

Alison Bechdel writes that this graphic memoir started as both a personal and cultural history of exercise, organized by decade: her obsession with yoga in the eighties, road biking in the nineties, and backcountry skiing now. Then it got a little out of hand. The premise of seems simple, but, like all of Bechdel’s work, it quickly gets into deeper questions about mortality, love, and obsession. By outlining the ways she’s chased the thrill of exercise since she was a small child, and how it’s shaped so many of her choices and relationships, she explores how fitness fads influence our sense of self. It’s why people get so obsessed with Peloton or wear shirts that proclaim “I am a skier.” The resulting book is smart and tender and funny and true. If you’re someone who doesn’t quite understand your own compulsion to exercise, or who secretly worries it might be related to your fear of growing up and slowing down (raises hand), I’m willing to bet that this read will resonate. —H.H.

Outlawed, by Anna North

What’s your ideal pandemic read? Mine is either escapist fiction or a savvy cultural critique, and Anna North’s , a feminist twist on the classic western bandit story, somehow manages to be both. In a reimagined 19th century, where a flu has killed the vast majority of the U.S. population, a religious regime has taken over the government and childless women are hung as witches. Ada, a teenage midwife who fails to have kids in her first six months of marriage, is banished and falls in with a band of gender-nonconforming outlaws. ���ϳԹ��� (obviously) ensues, but the story also sheds light on many current cultural questions about identity, morality, reproductive rights, and mob mentality. It would be a feat even if the writing wasn’t beautiful, which it is. —H.H.

Fuzz, by Mary Roach

If anyone can find delight in a house rat, it’s Mary Roach. studies fraught relationships between people and animals, taking readers from the penguin colonies of New Zealand to the dumpster-diving bears of Aspen, Colorado. At its core, every chapter asks: How do humans stop animals from breaking our laws? The key lies in the science of animal (mis)behavior. But instead of just interviewing experts, she also gets involved—building vulture effigies, tracking man-eating leopards, and even getting robbed by monkeys. Roach reports these experiences with her signature wit in this curious, big-hearted exploration of the creatures we love and loathe. —R.H.

Something New Under the Sun, by Alexandra Kleeman

In Alexandra Kleeman’s climate-change noir, an actress named Cassidy lives in a version of L.A. where everyone drinks lab-made water. The texture is like “the gag of your throat when you swallow a hair,” she says. “It’s less a flavor than… the awareness of a presence.” The man-made water is just one unsettling feature of ’s vaguely dystopian setting, which includes familiar motifs like wildfires, droughts, and resource crises. For the rest of the novel, Kleeman expertly builds on that feeling that something is not quite right. Patrick, a writer who arrives in the city to adapt his book into a movie, slowly begins to uncover a corrupt corporate plot. (And about that water….) The book entertains with eccentric characters, a compelling mystery, and bizarrely funny observations about consumerism’s rotten core. —E.B.

A Shape in the Dark, by Bjorn Dihle

Danger always lurks in the Alaskan bush, and you won’t forget it in this nonfiction tribute to bears. There are plenty of bear stories out there, but what differentiates —part history, part adventure narrative—are its striking prose and stoic sensibility. Here, grizzlies appear as “gothic monsters in the rain and mist,” and their tracks “radiate with death.” By resisting sensationalism, Dihle comes across as a convincing authority on everything from terrifying bear maulings to conservation legislation to trekking through bear country. The absence of a central narrative arc does not make this read any less compelling. Dihle’s no household name yet, but he should be. —R.H.

Below the Edge of Darkness, by Edith Widder

As a teenager, Edith Widder nearly went blind due to complications from a surgery. The near miss shaped how she thought about sight, light, and darkness, and it guided her into a career studying marine bioluminescence. She doesn’t water down the science for a layperson audience; you’ll find ample descriptions of the processes behind different forms of luminescence and also of anglerfish mating rituals. But Widder, who was awarded a MacArthur grant in 2006, also vividly renders what it’s like to step into a submersible, alone, and sink down thousands of feet below the ocean’s surface toward the liminal space that she calls the “edge of darkness.” “The response is universal—a heady fusion of joy and awe,” she writes. is a memoir, travelogue, and bracing reminder of how humans are already causing irreparable damage to stretches of the planet that we know very little about. —K.C.