Reading the autobiography of any elite athlete devoted to an extreme sport—or, in the case of surfing, the radical zone of an otherwise benign and accessible sport— you might find yourself wondering how the author ever stayed alive long enough to write the book. It requires a great deal of luck, and William Finnegan’s memoir ($28, Penguin Press) is at its heart the chronicle of a lucky man.

A pair of writers in parallel universes, Finnegan and I have ridden many of the same literary swells, but as a surfer he kicked my ass and left it high up on the beach thirty years ago. If I’m doing the math right, the only time I ever crossed paths with Finnegan in the water was on the south shore of Oahu in the mid-sixties, when I was a 14-year-old East Coast kook on a Hawaiian vacation with my parents and he was a 13-year-old California transplant, there for a year and then gone—a foreshadowing of his extraordinary promiscuity in the decades ahead, paddling into uncharted waters for a week or a month, a pilgrim and at times a pioneer, a free spirit whose professed ambivalence for the surfer’s lifestyle and what he calls its “incessant demands” never really put a dent in his almost religious obsession. “Calling surfing a sport,” writes Finnegan, “did get it wrong at nearly every level.”

Chronically peripatetic, Finnegan never anchored himself until he moved to Manhattan in the 1980s and became a staff writer for The New Yorker. There he achieved deserved fame for his words and reportage, if not for his tubes, though Barbarian Days will surely correct that imbalance.

I’ve always considered it a type of sin against the vast and wondrous panorama of life to make your world small, shrink-fitted to convenience, immunized against change and unfamiliarity. It’s the experience-hungry girls and boys like Finnegan who inherit the earth, but when you add up all the journeys, a simple rundown of the book’s chapters is unrevealing. Finnegan surfed here, here, and here times a hundred. Asia, Africa, the South Pacific, Hawaii, Portugal, Long Island, the British Isles, Mexico, the moon.

There are thematic templates for how to read and comprehend a work of literature, a framework that doubles nicely as a way to understand human nature and a person’s life. There’s man against man, man against nature, and, finally, man against himself. It’s when Finnegan works these dynamic currents that Barbarian Days becomes more than a journal of time and destinations. What are the vulnerabilities of a solitary self, never more alone than on the ledge of a big wave? What of the unavoidable competition among one’s brothers? The impact of the almighty ocean on one’s psyche and character? The self-questioning that attends risk and recklessness? The quest for identity and how it aligns, or not, with the quest for purity and beauty? When Finnegan paddles into that lineup, he’s fearless and full of grace.

On Our Nightstand

Two celebrated authors explore humankind’s fragile, not always friendly rapport with the animal kingdom in new novels.

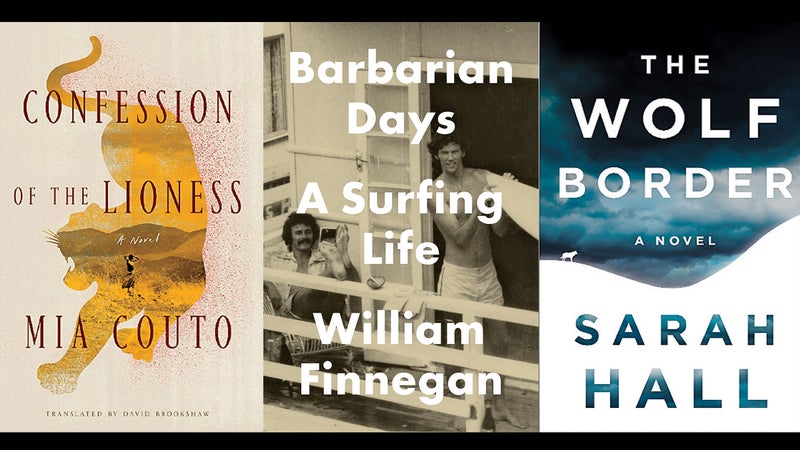

, by Sarah Hall ($26, HarperCollins)

The Gist: An expat zoologist returns from Idaho to help an earl reintroduce wolves in the northern England countryside.

Management Tools: Industrial-grade fencing, GPS

Result: Success!

, by Mia Couto ($25; Farrar, Straus and Giroux)

The Gist: Hunters try to protect a small village in Mozambique from a barrage of deadly lion attacks.

Management Tools: Rifles, spells

Result: Semi-success.