On January 14, 2015, Tommy Caldwell and Kevin Jorgeson topped out El Capitan’s Dawn Wall in Yosemite Valley to a circus of friends, family, and media. Their 19-day push to complete the first free ascent of the wall captured attention far beyond the climbing community. But the story of their cutting-edge ascent begins long before that winter, or even the seven years that Caldwell, joined later by Jorgeson, had attempted what’s considered the hardest rock climb in history. The story of the Dawn Wall is the story of Tommy Caldwell.

, the long-awaited documentary film from Red Bull Media House and Sender Films, delivers Caldwell’s story in full, from childhood to his capture by militants in Kyrgyzstan and his passion for big-wall free climbing, in which equipment is used only to catch falls. Of course, highly accomplished free climber and boulderer Jorgeson plays a central role in the film as the other half of the climbing team, but The Dawn Wall focuses heavily on Caldwell, the visionary behind the climb. Through moving interviews, the film explores Caldwell’s inspiration that led to the seven-year project. But the documentary skims over his darker motivation: a deep depression that would ultimately lead him to the greatest accomplishment of his life.

About 30 minutes into The Dawn Wall, we see Caldwell in the winter of 2007, following a divorce and at the lowest point of his life, sitting on top of the Rostrum in Yosemite, staring at El Cap. But there was more to this scene than the film suggests. In the documentary, Caldwell seems to be simply contemplating the scenery, and the shot is included as backstory with voiceover and reenacted footage. The scene leaves out that he was wearing only shorts, climbing shoes, and a chalk bag and intended to free-solo (climb without equipment or a partner) a 1,000-foot detached spire below. It would be his warm-up for a free-solo attempt of El Cap, a feat so risky that, at the time, it had never been done before. Caldwell had always viewed free soloing as selfish, reckless, and stupid. “But what if I allowed myself to be just as selfish?” he later wrote of the moment in his memoir, . “If I took away the rope, the experience would be that much stronger. That much more real…And if I fell to my death, at least the pain would be gone, too.”

As Caldwell watched the sunrise that morning from the Rostrum, the first rays illuminated one section of El Capitan. The sight of the aptly named Dawn Wall jogged his memory, reminding him of the optimism he’d felt years before when he scoped out the potential for a free climb on it. It was the biggest and steepest unfreed swath of rock remaining on the 3,000-foot granite monolith. At the time, he thought it looked impossible—there were too many blank sections. But that day on the Rostrum, it was exactly that improbability that fascinated him. Caldwell needed a distraction from heartbreak, but instead of soloing to his death, he would throw himself at the Dawn Wall, a climb “infinitely harder than anything I had even contemplated climbing,” he wrote.

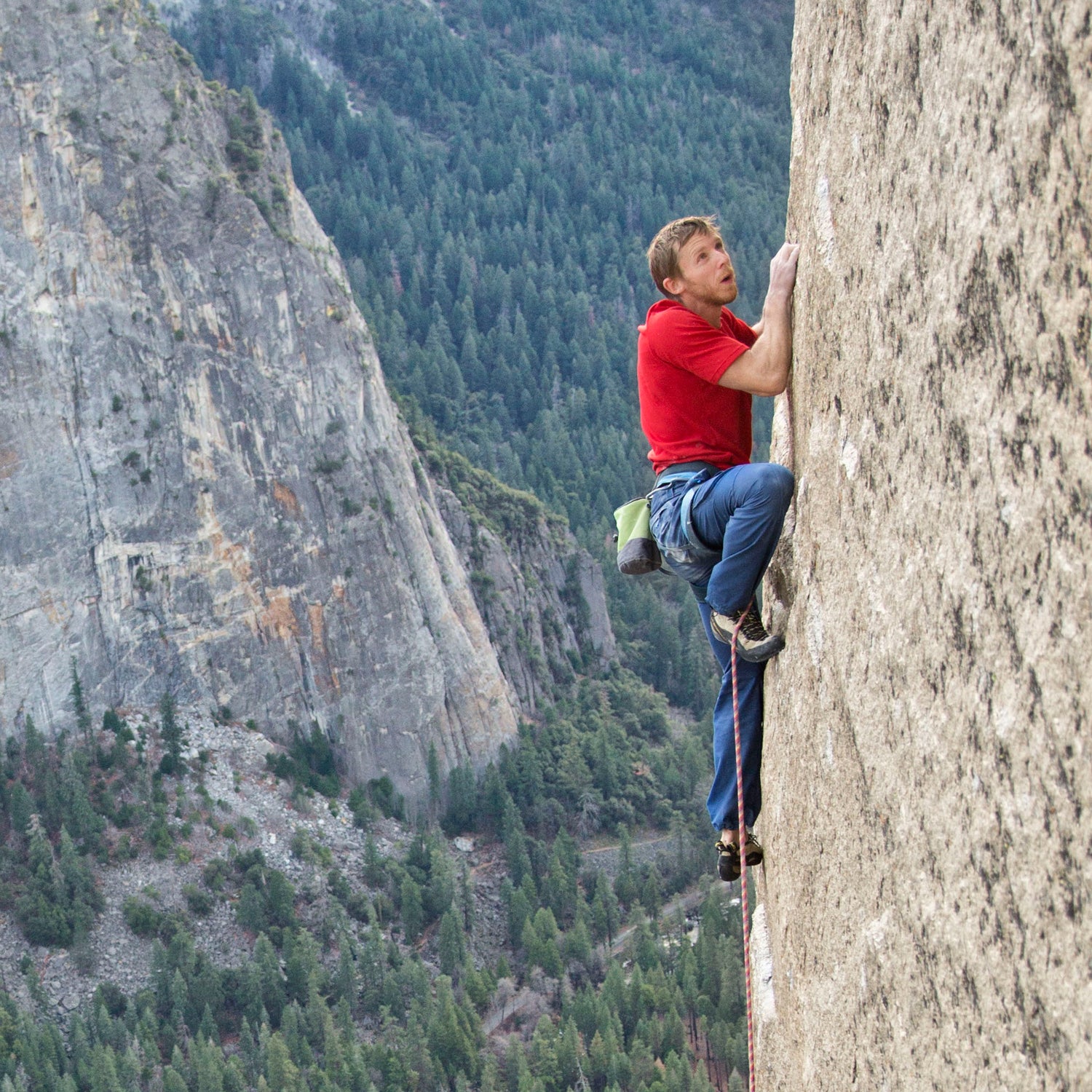

Unlike “climbing porn” flicks of the past, The Dawn Wall has substance beyond action shots. Directors Josh Lowell and Peter Mortimer strategically intersperse the backstories of Caldwell and Jorgeson while taking us through the Dawn Wall ascent, day by day and pitch by pitch, including the more ordinary moments, like shitting off the side of a portaledge. That’s not to say there isn’t an abundance of stunning climbing footage—there’s enough in the 100-minute film to make your hands sweat. The Dawn Wall has more difficult pitches than every other free route on El Cap combined. “This is, like, the hardest thing you could ever do on your fingers, climbing this route,” Caldwell says in The Dawn Wall. “It’s just grabbing razor blades.”

But this isn’t just a movie for core climbers. The Dawn Wall includes interviews with Caldwell’s parents, Jorgeson’s mom, friends of the climbers, and John Branch of the New York Times to provide an outside (read: human) perspective on the ascent. John Long, author and Yosemite climbing legend, narrates sections of the film to explain technical climbing jargon, big-wall tactics, free climbing, and climbing culture. The narration, coupled with visual overlays of features on the El Cap route, makes such a monstrous climb easier to digest—at least from the couch—yet for seasoned climbers does not feel hyperbolic or monotonous.

Some behind-the-scenes details, however, are left out. The film makes it seem as if Caldwell and Jorgeson were alone on the wall, when in reality they had a dedicated support crew who helped make the ascent possible. Caldwell and Jorgeson climbed the route in a single push from the ground up, which meant they had to live on the wall until they reached the top and needed a regular supply train of food, water, and amenities. According to James Lucas, a former Yosemite Valley bum and now associate editor at Climbing magazine, approximately 800 pounds of food and water were hauled up the wall over the course of the ascent.

Alex Honnold carried up lip balm and sunglasses one day. Lucas brought up 40 pounds of groceries in one load, including salami, pesto, cans of chili, red bell peppers, penne, rice, cucumbers, eggs, brown sugar, and a bottle of bourbon. To reach Caldwell and Jorgeson’s portaledge base camp (where they slept every night except the final night), friends, cameramen, and porters had to either hike to the summit of El Cap and rappel or jug 1,200 feet of fixed lines from the ground. For a time, Honnold held the jugging speed record at one hour, until Lucas, on a second trip to bring Caldwell tea and a keypad so he could type updates to the world, jumarred in 54 minutes.

I write this not to take away from their achievement—it’s just the opposite. The Dawn Wall project was so insanely difficult that it took a community to make it possible, and in my mind, that makes it all the more impressive. A single-push, ground-up first ascent of the Dawn Wall likely would not have been possible without outside assistance—something Caldwell accepts in a feature he wrote for Ascent in 2011, while he was still projecting the climb: “I used to shun help from others…but El Cap climbing seems to be going in the direction of using porters to haul and hike loads to allow the climber to save strength for free climbing.”

Earlier in the same article, Caldwell wrote, “A free ascent of the Dawn Wall would mean catapulting forward what I thought was possible in the world of big-wall free climbing.” With his mind set on the project, Caldwell would spend years hanging off the side of El Cap attempting to connect the dots of cracks and crimps to find a continuous free route to the summit. When he was not on the wall, Caldwell would train back at his home in Estes Park, Colorado.

“I think we all admire people who are dedicated, but at some point you start to wonder where the line is between dedication and obsession,” Kelly Cordes, a climber and friend of Caldwell’s, says in the film.

For Caldwell, the Dawn Wall came down to a simple choice: to give up on life or raise the bar. He made his decision and gave the world the Dawn Wall. What the documentary doesn’t tell you is just how close to the edge Caldwell had been.

The Dawn Wall opens nationwide on September 19 for one night only. Tickets are available now at .