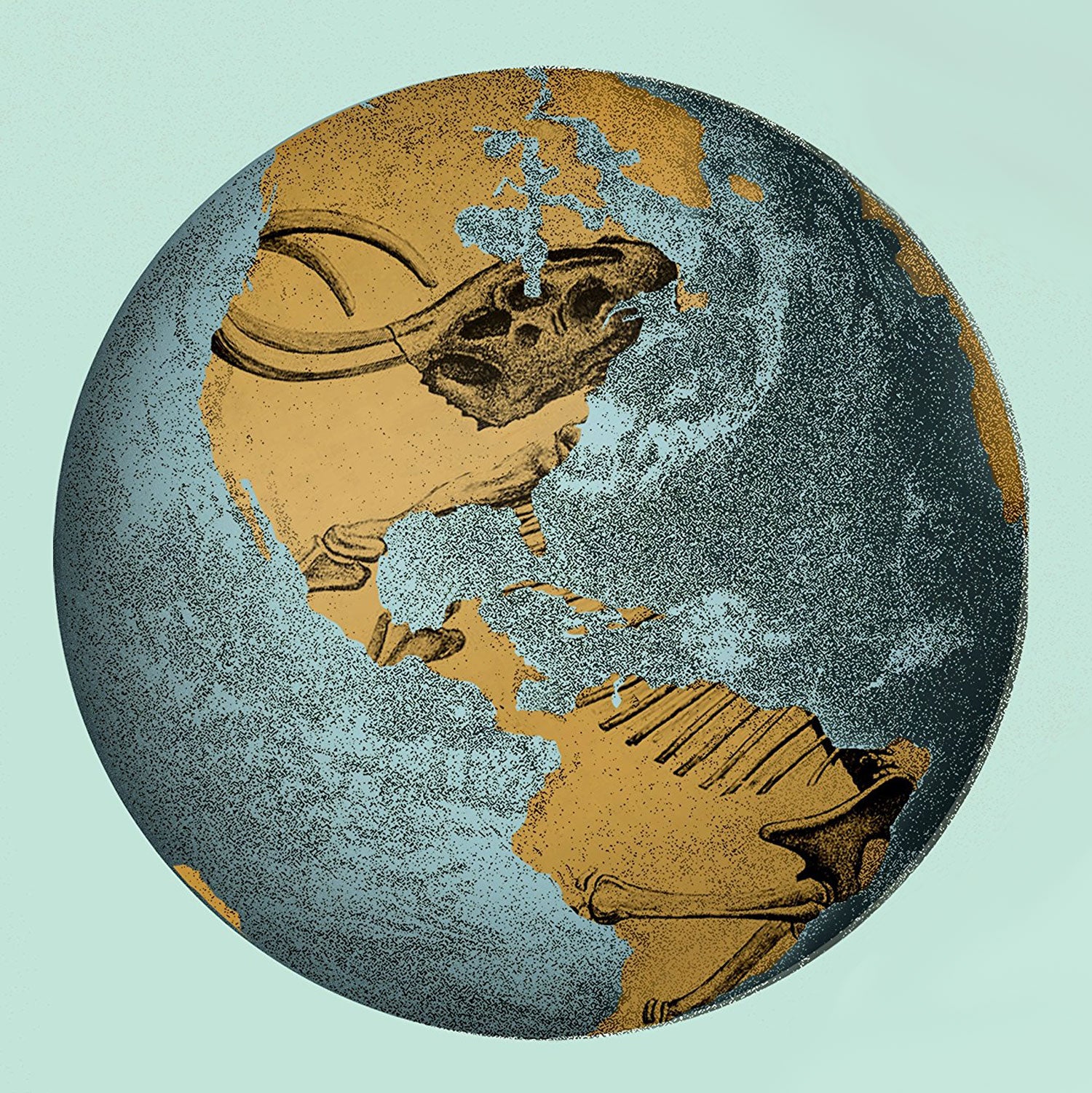

Twenty years ago, was lying in a Colorado cave, alone with a Pleistocene-era camel skeleton he was helping excavate as part of his graduate research in desert studies. He realized that he was one of the first people to ever see the camel, which had lived before people inhabited the States. “I was spending all this time with these bones and imagining what it looked like before people were there,” he says. North America was one of the last major places on earth to be occupied by humans, sometime between 20,000 and 40,000 years ago, and that idea—of what the unexplored continent looked like when people first crossed over the land bridge from Asia— has stuck with him for two decades. In his latest book, he goes back into the cave, and then all over the world, to trace humankind’s initial exploration of the Americas.

Childs is known for meshing anthropology and exploration in books like . The new book, , pulls together the themes of his past work and lets him explore the questions he’s been marinating on for more than two decades. He traveled from the Yukon Flats of Alaska to Quintana Roo, Mexico, to try to learn from the people who came to the continent first. We talked to him about exploration, ancient history, and why his research sent him to Burning Man.

On Traveling for the Book: My history with writing is about time and archaeology, so I want to see where the blank places are, and how the threads got connected place by place. I went to Saint Lawrence Island, one of the last pieces of the Bering Land Bridge, which was the last landscape people would have seen 20,000 years ago when they were crossing over. That was pretty compelling to me because it was such a meeting point between two different parts of human civilization.

On His Most Unusual Book Destination: I was in Black Rock Desert during Burning Man, which was intentional. I was writing about the first large gatherings of people, at the end of the Pleistocene in [what’s now] Massachusetts. It has the same layout and the same concept: people coming together to share ideas. We’ve gotten somewhere on scale—there’s way more of us—and we’ve opened ourselves up to understanding things like scientific processes we didn’t understand then, but we’ve given up a lot, too. There’s a lot of knowledge of plants and animals we’ve lost.

On Where He Was Most Surprised By What He Saw: When I’m in the backwoods of Florida it’s all new to me. There were times we might have been in people’s backyards, but it felt wild. In some places you can employ the skills you picked up on western rivers, but it’s not that easy there. There were snakes hanging out of trees, and alligators, and there were times I was in over my head. The rivers were bewildering. I’d follow them and they would go into holes in the ground, then I’d walk farther, and they’d come out of different holes.

On Research and Reading Material: Half of the book is brain work with other researchers and half is foot work. I rely heavily on other people’s research, so mostly what I’m reading is hundreds upon hundreds of scientific journal articles. But the place I start from is fiction because I want to see what they’re doing in more sharp-edged writing. I always go back to . And lately I’ve been reading poetry, Sharon Olds and Mary Oliver. I can open up a page, get blown away, and set it back down.

On What He Learned: It’s about species colonization. Every species has to have a certain number of individuals who are willing to go out looking at the edges of things to see if there’s a niche they can move to, or a new resource they need for long-term survival. I think it’s true now, too. It’s no wonder we’re consuming everything so quickly.

On Why People Explore: A Pleistocene sense of landscape is still within our grasp. You can still go have those experiences, and I think it’s why we hike and put on packs. We remember what it’s like to make decisions, and to scan the horizon with every step. When you drop in there and pretend you’re first, how do you learn about the plants and the place? You learn how to adjust to the landscapes.

On What He Hopes Readers Get from the Book: What I really want people to come away with is context. We get lost in thinking that this is the only moment. We see history only going back 3,000 years, but the country as we know it now has a much deeper story. I think if we understand the arc of where we’re going as a species we can make more intentional, informed decisions.

Like the sound of Atlas of a Lost World? Here are some other books to add to your list:

�� by Yuval Noah Harari

Really want to know how we got here? Harari’s human history goes deep on everything from biology to economics to try to understand.

�� by John McPhee

The similarities don’t stop at the titles. McPhee is the master of pulling together disparate people and places to show the ways the systems we depend on are built. he’s also the master of getting readers to care about something—geology!—they might have otherwise ignored.

“” by Ross Andersen, The Atlantic, April 2017

Andersen’s weird, wonderful article about a recreated Ice Age biodome in Russia asks some of the same, bittersweet questions about what we’ve failed to learn from the past.