Last month, the International Olympic Committee (IOC) and the Japanese government announced that the 2020 Tokyo Games would be┬ápostponed┬áuntil┬áJuly 23, 2021, due to the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. ItÔÇÖs clearly the right call. But maybe you, like me, are still in shock, confronting the loss of an event weÔÇÖve been looking forward to for years.

Four recent books, however, remind us of other times when the Olympics overcame global crises and persevered through dark periods┬áduring┬áits 124-year history. There were the World Wars, of course, which resulted in┬áthe cancellation of three Games. But it carried on through the Great Depression, terrorist attacks, and, most recently, a rogue regime threatening the use of a nuclear bomb. So while youÔÇÖre sheltering in place without sports for the foreseeable future, try one of these reads to put this moment in historical perspective.

The Time an Olympic Hockey Team Helped De-Escalate a Nuclear Threat

The Olympics are often as much about politics as they are about sports. That was certainly true for the┬á2018 Pyeongchang Games, which helped ease tensions between South Korea and North Korea, even though┬áorganizers feared the latter might test a nuclear weapon during competition. In the middle of this geopolitical chess match was KoreaÔÇÖs first-ever unified womenÔÇÖs ice-hockey team. South Korea originally proposed the idea as a symbolic gesture to mitigate the tension on the Korean peninsula. Kim Jong Un┬áeventually bought in, and a squad┬áof 23 South Koreans and 12 North Koreans was created. In , Seth Berkman, a sports contributor at The New York Times, unspools┬áthe fascinating backstory. ÔÇťEveryone on the team has a story worth sharing,ÔÇŁ he told ║┌┴¤│ď╣¤═°.

The ups and downs that led to the unified team are especially engrossing. In 2013, South Korean officials sent mysterious emails┬áto recruit Canadian and American collegiate players who looked Korean in their yearbooks. As a result, five North Americans of Korean descent joined the roster, which at that point was comprised solely of South Koreans. And the players didnÔÇÖt just hail┬áfrom different countries but┬áall walks of lifeÔÇöthey were college students, actresses, convenience-store workers. They became close as they prepared for the Olympics┬ábut then, four weeks before their first game in Pyeongchang, found out that 12 North Koreans would be joining the squad. In the end, everyone┬ádeveloped a special connection through training sessions, K-pop songs, Big Macs, and ice cream.

While the group didnÔÇÖt win a single match, it wasnÔÇÖt all a loss. Their teamwork overcame cultural, societal, and political challenges to make history. And the Olympics helped get Donald Trump and Kim Jong┬áUn to the negotiating table, which, at least for a while, provided hope for the denuclearization of the Korean peninsula.

The Time an Ex-Cop Saved Thousands from a Bomb at the Olympics

The Atlanta bombing at the 1996 Summer Games was the worst Olympic terrorist attack since the Munich Massacre of 1972. Still, until , at least, most people forgot about Richard Jewell, the heroic security guard who spotted the bomb and prevented greater calamity. In , Kent Alexander, U.S. attorney for the northern district of Georgia at the time of the 1996 Olympics, and Kevin Salwen, a seasoned journalist, bring us back to the eighth night of those Atlanta Games.

At Centennial Park, Jewell, a hapless former cop turned hypervigilant guard, spotted a discarded bag near thousands of spectators watching a concert. It turned out to be a bomb. He helped evacuate the crowd, but it was too late to save everyone. It exploded. Two people died, and 111 were injured. In the following days, newspapers and TV networks from all over the world hailed Jewell as a hero. Everything went south, though, once an FBI agent leaked to the Atlanta Journal-Constitution that Jewell was a suspect in the attack. Law enforcement finally cleared him after three months of investigations, but during that time, TV crews in vans and helicopters shadowed Jewell and his family, speculating that he was the bomber. In 2003, the actual perpetrator, an American named Eric Rudolph, was captured and confessed not only to the Olympic bombing but three other antiabortion and antigay terrorist attacks in the South as well. Yet even today, some people continue to think Jewell is guilty.

Alexander and Salwen conducted 187 interviews and sifted through 90,000 pages of documents over five years while researching the story. They concluded that the Jewell episode was, as they write in The Suspect, ÔÇťconvenient for law enforcement that got its suspect. Convenient for the media that got its story. Convenient for Olympics organizers who could move the Games forward with fans and athletes believing the bomber had been safely cornered.ÔÇŁ It was convenient for everyone but Richard Jewell himself. False information spread widely, shaped public opinion, and dragged law enforcement in the wrong direction. After that┬áit was hard for the suspect to recover his life┬áand his reputation. In an interview with , Salwen says the tale is ÔÇťa social-media story from a time when social media didnÔÇÖt exist.ÔÇŁ

The Time the Olympics Arrived in America During the Great Depression

Los Angeles has Billy Garland to thank for putting it on the map: the real estate tycoon brought┬áthe Olympic Games to that city in 1932, helping establish it as the global cultural capital it is today. Yet most people in Southern California have probably never heard of him. Pulitzer PrizeÔÇôwinning journalist Barry Siegel revives his incredible story┬áin .

At the turn of the century, automobiles were a rare sight in the underdeveloped city, and fig orchards covered what would become the Hollywood Hills. The movie industry only started to take root the following decade, and by 1920, three-quarters of the worldÔÇÖs films were shot around Los Angeles. But when the IOCÔÇÖs European establishment began searching for the host of the 1932 Games, Los Angeles was still not on its┬áradar. Garland decided to change that. Dreamers and Schemers uses extensive archival material, including letters exchanged between Garland┬áand Pierre de Coubertin, the founder of the modern Olympic movement, to recount GarlandÔÇÖs improbable effort to bring the worldÔÇÖs largest sporting event to the City of Angels.

Some document-heavy sections move slowly, but the book conveys the amazing amount of ambition and confidence it required to convince both European representatives in the IOC and Californians themselves that the Olympics should come to Los Angeles. Garland pushed the state government to issue a million-dollar bond┬áand then corralled Hollywood and local newspapers to drum up morale for hosting, even as the Great Depression rocked the country. He endured┬ápolice corruption and political scandals to produce a successful Olympics, introducing┬áLos Angeles to the world. ÔÇťThe story of Billy Garland is the story of Los Angeles,ÔÇŁ Siegel writes. And thatÔÇÖs not an exaggeration.

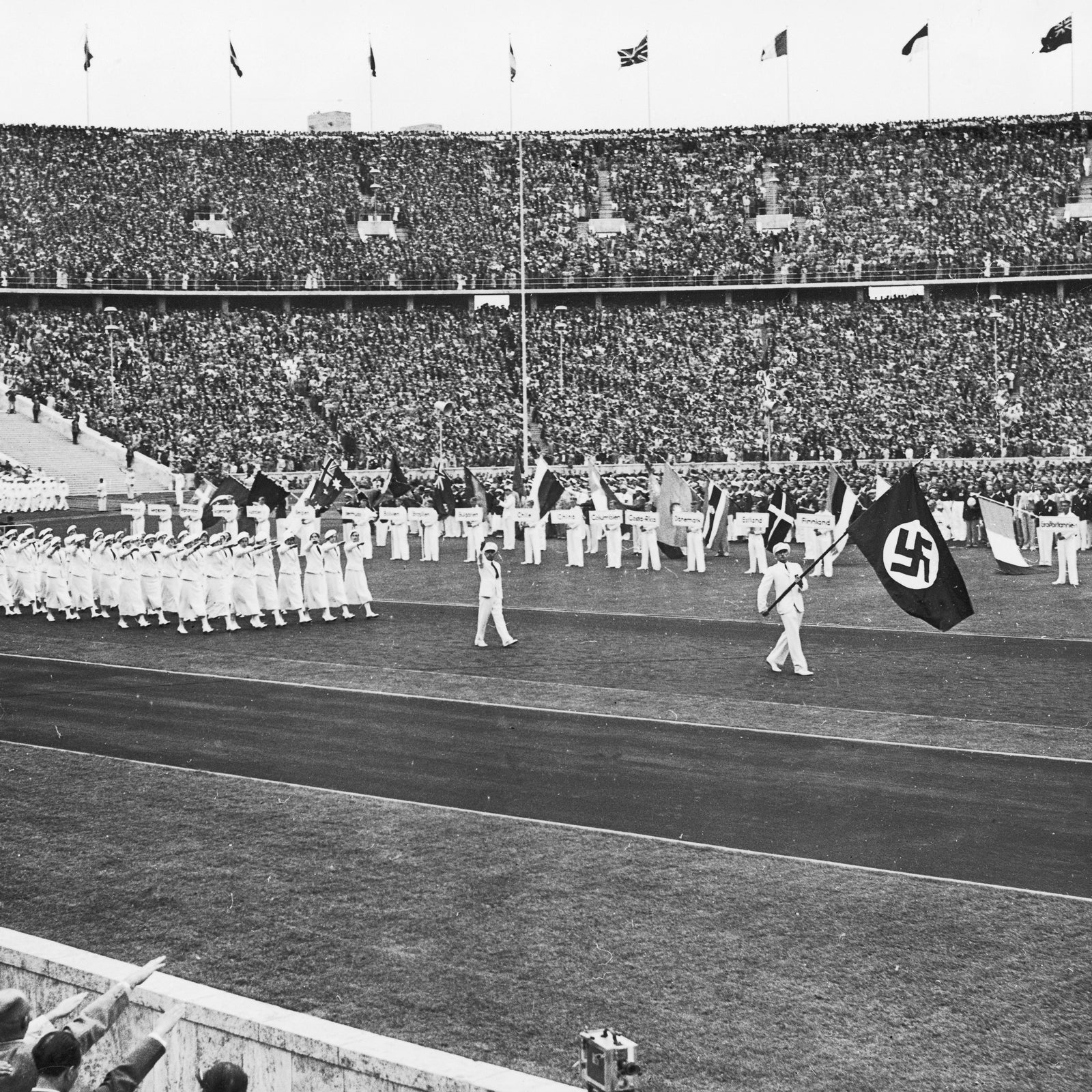

The Time a Group of African American Athletes Defied Racism and Fascism to Compete in the Olympics

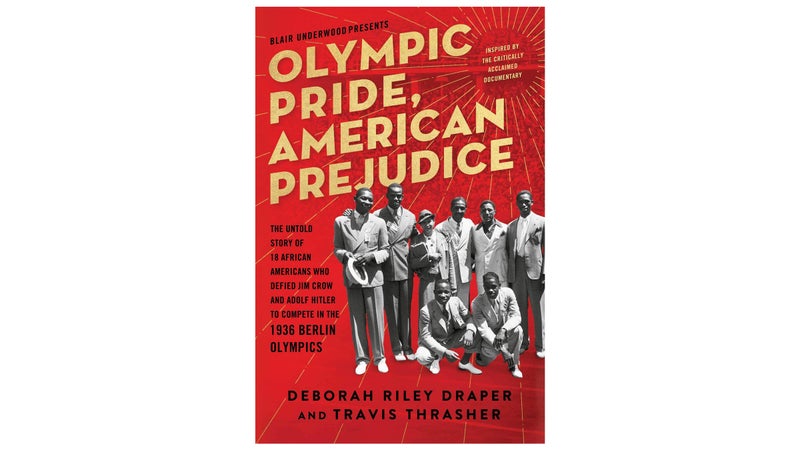

Typically, the world only remembers one black athlete from the notorious 1936 Berlin OlympicsÔÇöJesse Owens. But in , based on , director Deborah Riley Draper and author Travis Thrasher tell the story of the other 17 African American athletes who competed in those Games.

Their presence and victories in Berlin were┬áa blow to racial prejudice on both sides of the Atlantic, and the book, though sometimes scattered, explores their fascinating backstories. The athletes pushed┬áthrough unfair and rigorous trials to represent a country that considered them second-class citizens at an Olympics┬áhosted by a fascist country. In some ways, Nazi Germany actually treated them better than the Jim Crow South. Owens and his fellow African American┬áathletes were welcomed with applause and respect from competitors and spectators, and they all stayed in an integrated Olympic Village. Then┬áthey defied the Nazi regimeÔÇÖs ideas of Aryan superiority by scooping up 14 medals, including seven golds, in track and field and boxing.

ÔÇťIt wasnÔÇÖt just Jesse. It was other African-American athletes in the middle of Nazi Germany under the gaze of Adolf Hitler that put a lie to notions of racial superiority,ÔÇŁ write┬áDraper and Thrasher. The athletic excellence demonstrated by the group foreshadowed HitlerÔÇÖs defeat in Germany┬áand, back home, was a precursor to the civil rights movement.