I started thinking about my hands. That was my first mistake.

After 48 days and more than 760 miles alone across Antarctica, the daily ache of my hands—cracked with cold, gripping my ski poles 12 hours a day—had become like a drumbeat, forming the rhythm of my existence. And that night, the ache got to me. As I pulled my sled into a blizzard of cold and white—my jacket thermometer read 30 below Celsius, with blasting gusts of wind that made the windchill at least 50 below—I started picturing how intensely pleasurable it would feel to get out of my mittens.

I saw myself securely inside my tent, massaging life back into the sore, stiff, cold-battered knuckles, holding them close to the hissing flame of my stove, pressing them up against the little aluminum pot as it began to warm and melt the snow for my drinking water and dinner.

At about 8 p.m., with the 24-hour sun just a pale yellow dot overhead through the thick clouds and blowing snow, I stopped to make camp. I unhitched from the harness that connected me to the sled, unzipped the cover, and fished out my tent.

Then I paused for a moment, hunched over in the cold, looking down at the tent in my hands. I’d made camp in storms and sun and wind, and I’d always done it the same way, through muscle memory forged by repetition—anchoring one end of the tent to the sled, then driving anchors into the ice at the opposite end and around the perimeter. It was the most secure way.

But that night, in my fatigue, and with the cold ache of my hands crying for relief, I decided that a simple stake into the ice would be good enough, rather than securing it to the sled. It was much faster. It would be fine, I told myself.

I rushed it. That was my second mistake.

I drove in the stake, unrolled the tent flat, and walked back around to the far end. I knelt down on the ice and pushed the spring-loaded tent poles into their little metal grommets, popping the tent up. The next step also felt utterly routine, at first. I inched back and pulled the tent toward me, straightening it out into a point of tension with the first anchor, preparing to put a second stake down into the ice.

Then it happened. At exactly the wrong moment, before my second anchor was secure, a monstrous gust came straight at me over the top of the sled, as though it had been taking aim from the farthest reaches of the continent. Between my yanking on the fabric and the sudden blast of wind, the first anchor I’d planted on the tent’s other side lost its grip in the ice.

In the next instant, I saw the far side of the tent rise up, now unsecured and disconnected. The horror of the scene flooded through my body as though I’d stuck my finger in an electric socket, but it almost seemed like slow motion—as the tent, with each new inch off the ice, caught more and more of the oncoming wind from beneath.

And because I’d just pushed the tent poles into place, popping up the semicircle spine of the frame, there was more surface area to catch the wind. So, as the tent rose, it caught greater and greater force, like a kite or a sail. In a split second, I lunged forward and barely grabbed the edge of the tent, making me the tent’s sole attachment to the planet.

What could happen next played out before my eyes like a waking nightmare: I lose my grip. The tent rises, I leap desperately for it but can’t catch it, and I stumble and fall. The tent disappears almost immediately into the white. I get up and run for it into the storm…and then…and then…I am lost. The tent is gone. I turn back and see nothing but the full whiteout of the storm. I have nothing to guide me back to the sled and no hope of surviving the night.

The horrible vision kept playing out as I held on desperately.

I had no backup tent. No rescue party could ever make it through a storm like this, with zero visibility and rugged, uneven terrain that would prevent a plane from landing. I’d grow sleepy, then increasingly irrational, and finally I’d just lie down, thinking that the ice was a nice place to rest. I’d die alone, in the cold, my body temperature falling.

It wasn’t the fear of death that really got to me—it was the realization that I’d never make it home. I’d never get back to Portland; never walk along the Willamette River holding hands with my wife, Jenna; never laugh around another campfire at the Oregon Coast with my parents and the rest of my family; never again smell the deep, peaceful aroma of a damp, bark-lined forest trail in the Cascade Mountains.

My hands were now everything. They gripped the edge of the tent as my airborne home yanked and jerked over my head. I knew everything depended on what happened in the next few seconds—on how long I could hold on and what I did or didn’t do.

I knew I had to flatten out the tent somehow so that it wasn’t catching so much wind. But the only way I could think to do that—pulling it down and crawling on top of it to hold it with my weight—might snap the tent poles. That would create a different crisis. Aiming to save a bit of weight on the sled, I’d left my spare poles behind on a brilliant sunny morning that now felt like a lifetime ago.

As the wind blasted into my face, the cold deepening with every second, my panic increasing, I relived that sunny, long-ago moment of choice. I could feel those poles in my hand, see myself digging a hole in the snow and burying them along with other supplies and tools for later retrieval. All that equipment had seemed so heavy and so dispensable.

Maybe, I thought, that was actually my first mistake—the place where the great chain of error really began. Such a tiny thing, it seemed: tent poles. A few ounces saved, another mistake, and I was living the consequences.

Choices and consequences. Everything in the universe was simplified into those giant words. Overhead, my small tent seemed suddenly huge—a fluttering, flapping red monster, bigger and harder to hold with every passing second. And my cramping hands were starting to lose their grip.

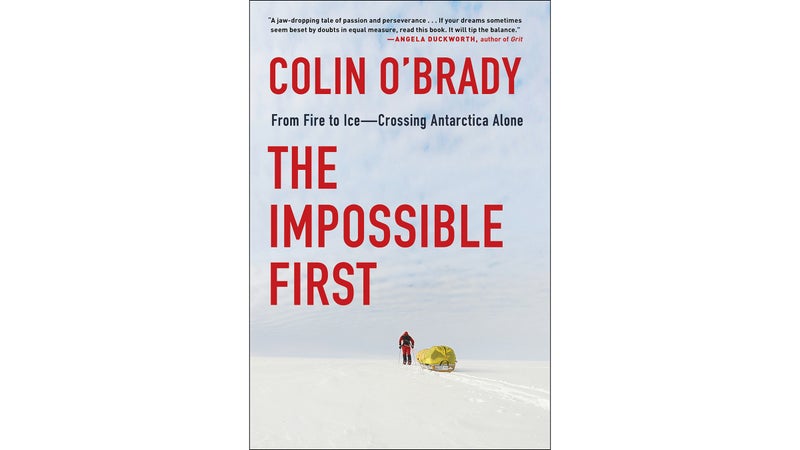

From by Colin O’Brady. Copyright © 2020 by Colin O’Brady. Reprinted by permission of Scribner, an Imprint of Simon & Schuster, Inc.