In the first climb that author Jan Redford narrates in her debut memoir, (Counterpoint Press; $26), she’s an adventurous 14-year-old enraged by yet another broken promise from her hard-drinking father. She charges out of her family’s vacation cabin in eastern Canada and into the woods, where she discovers a rock cliff four times the height of a house. Still fuming, Redford spontaneously scales the formation, scaring the wits out of herself and forgetting her anger at her dad.

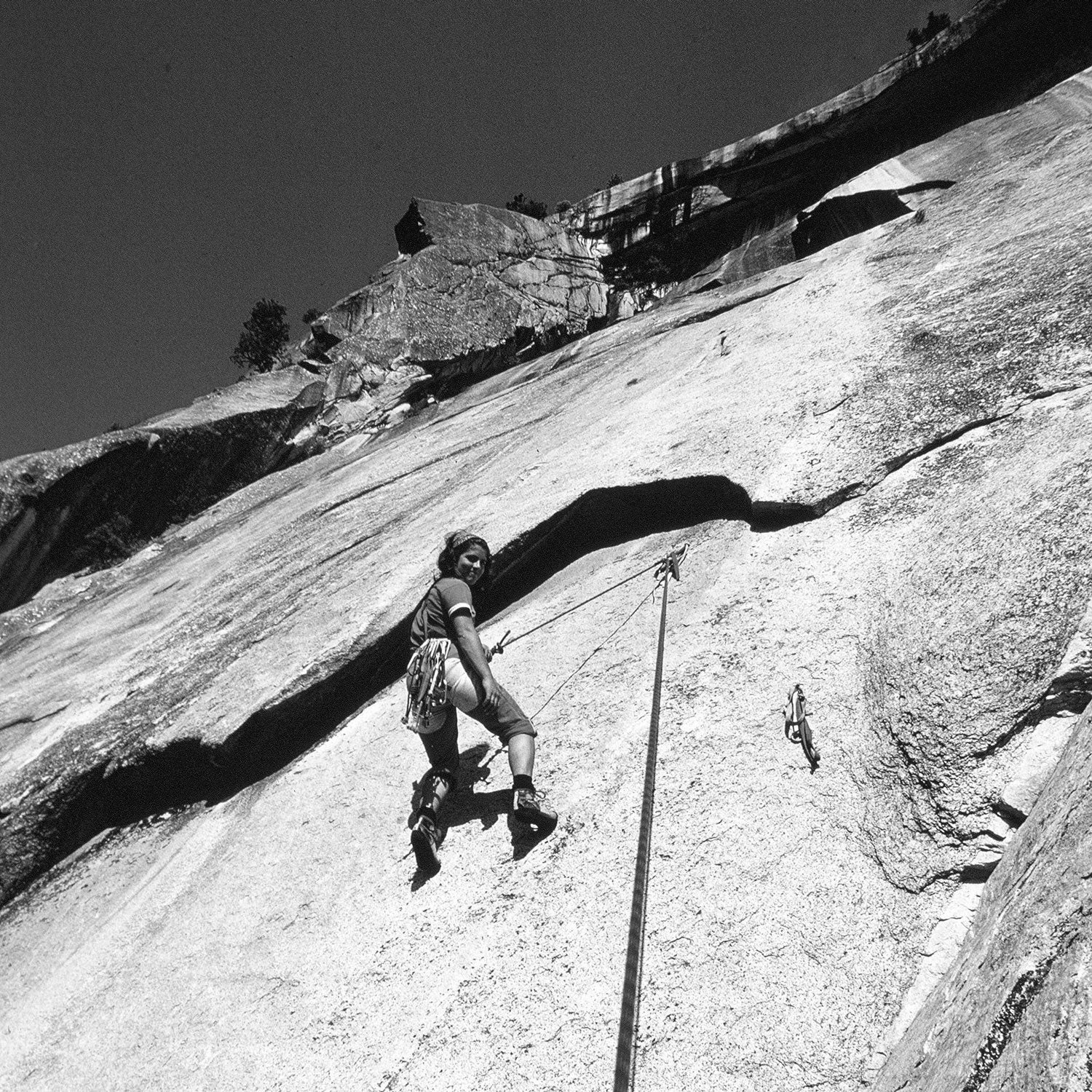

So begins Redford’s complicated relationship with both men and climbing, a struggle that will continue for at least the next two decades. It’s one of several threads in her memoir, recalling her gritty coming-of-age and her goal of becoming a professional guide—which she achieved in 1986, at a time when there were few other women guiding in North America. The book is a welcome addition to mountain literature, where women’s voices (and stories like lactating all over yourself in the woods while on the job) are still noticeably rare.

In a departure from typical climbing narratives, Redford doesn’t write about her greatest accomplishments on the rock—while she was a talented climber, she didn’t make first ascents or do expeditions on mountains like Everest. Instead, she shares her worst moments, from nearly rappelling herself off the end of the rope on 3,000-foot El Capitan to panicking while guiding a group of army cadets up what should have been a routine alpine summit in the Canadian Rockies. “I wasn’t writing about the things I did right, the climbs I breezed up and had a beer at the bottom,” Redford explained over the phone from her home in Squamish, British Columbia, the rock-climbing capital of Canada. “I was writing about the things I learned from.”

This includes her personal life and her early dirtbag days after catching the climbing bug. Redford officially learned to climb after high school, at the (NOLS) in Wyoming. As she writes of her 19-year-old self, “I felt like I’d been sleepwalking through my life, and climbing propped open my eyes. Made me fully alive.”

After NOLS, Redford goes full-bore climbing bum. She waits tables and works seasonal jobs doing ski patrol and tree planting in Canada to support her lifestyle. She dreams of becoming a professional guide but settles for dating them while she accrues more experience in the outdoors. The men she’s attracted to are always older. They’re also masters over their chosen outdoor dominion: alpinists, big-wall climbers, kayakers. Much as Redford is drawn to these men, she’s also dubious of softening, of losing her position as a foul-mouthed, tobacco-chewing, one-of-the-guys badass. Describing this apprehension after meeting a man during one of her five seasons climbing in Yosemite, Redford writes, “Rik was 25, four years older than me, and he was such a good climber that I knew I’d follow him around like a baby duck if I slept with him.” She maintains this straight-shooting style of self-awareness throughout the book.

Redford complicates her own narrative because she ������’t ultimately healed by the outdoors.

Redford starts to crave more stability when she meets Dan Guthrie. A big-wall climber, ice climber, and alpinist, Guthrie is arguably Redford’s first real love, and they’re soon living together at his place in Banff, Alberta, where Redford considers “getting my shit together” and attending university in nearby Calgary. In 1987, when Guthrie dies tragically in an avalanche while climbing in Alaska, Redford derails. Two days after the memorial, she ends up in bed with Guthrie’s good friend and climbing partner. Redford gets pregnant and chooses a shotgun wedding over an abortion.

Up until this point in the book, Redford has been following a storyline popularized by female adventure memoir authors like Cheryl Strayed: one that puts a greater emphasis on gaining control of our emotions than on mastering anything in the external landscape. While Redford continues to deftly handle this form in the second half of the book, she complicates her own narrative because she ������’t ultimately healed by the outdoors. More the opposite. Redford loses not only the love of her life to the mountains, but also one of her best girlfriends, Niccy, who falls to her death while teaching rock climbing in the Cascades. By age 30, Redford is an uneducated, unhappily married mother of two, living in a podunk logging town in British Columbia with her equally miserable climber-turned-logger husband. Redford eventually finds her way out of her failing marriage and dead-end life by leaving the mountains, moving to Calgary, and finally attending university.

In that way, Redford’s book tells the story that rarely makes it into an exciting adventure memoir—that of a person whose life ������’t magically transformed by climbing or who sometimes feels the betrayal of the wild more strongly than the benefits. The book is often more relatable than aspirational, and that can be a good thing.

While reading about another of Redford’s crippling episodes of self-doubt on the rock, I wanted to reach into the book and shake her. In retrospect, I may have been seeing a little too much of myself in Redford during those moments. Similarly, her mini epiphanies, on the rock and in life, resonated with me. In the epilogue, Redford writes about getting past fear while climbing: “If I can control my body, I can control my mind. I always thought it was the other way around. But if I put my body in motion, my mind has to follow.”

Much of Redford’s narrative may not strike readers as awe-inspiring in the way of the typical mountain-conquest story or as motivating as the increasingly typical healed-by-the-outdoors story. But it will resonate with anyone trying to find her path in a confusing world that still sends women far too many mixed signals about who or what we should be.