You’ve already heard about Wild. It’s Cheryl Strayed’s about hiking the Pacific Crest Trail in search of the healthy, happy woman she used to be, before her mother’s sudden death and the disintegration of her family. It’s about her search for a way out of what she’d become: a 26 year-old orphaned divorcee with an occasional heroin habit. And it’s the book that Oprah loved so much, she had to , in hibernation for the past two years, just to honor it.

Strayed is poised to become an author with the profile and sales of an Elizabeth Gilbert, and Wild an Eat, Pray, Love for the backcountry crowd. But while she may well have the top-selling, female-authored hiking memoir of all time on her hands, she’s not the first woman writer to lace up a pair of hiking boots. Here are five other epic memoirs of outdoor adventure, all written by women.

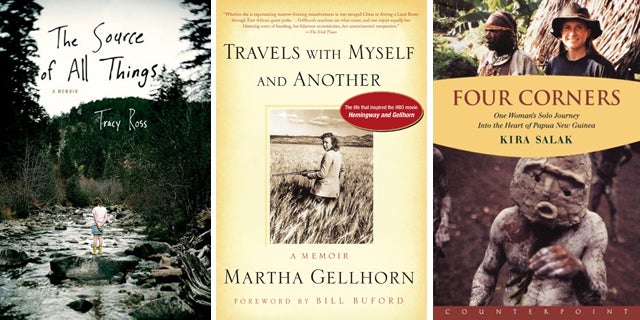

- Tracy Ross’ The Source of All Things

- Sara Wheeler’s Terra Incognita

- Beryl Markham’s West With the Night

- Martha Gellhorn’s Travels With Myself and Another

- Kira Salak’s Four Corners

Outdoor ���ϳԹ��� Memoirs by Women: Tracy Ross’ ‘The Source of All Things’

In 2009, Tracy Ross’ “The Source of All Things” won the National Magazine Award for essay writing. It told the story of a father-daughter hike in Idaho’s Sawtooth Mountains—during which Ross, now an adult, confronted her stepfather about molesting her throughout her childhood. The that evolved from that searing essay spans decades, delving deep into the abuse that began when Ross was eight, her eventual teenaged flight from her home, and the kaleidoscope of foster care, bad boyfriends, detours into self-destruction, and awkward family reunions that followed.

The American wilderness is the thread that connects the shattered pieces of Ross’ life: from the Sierra Nevada, where her biological father died on a backpacking trip when she was just seven months old, to Idaho’s Redfish Lake, where the abuse began, to the woods surrounding the northern Michigan art school where she made one of her escapes. And it’s the wilderness—in Utah, Alaska, Colorado, and back home in Idaho—that eventually saves Ross. But The Source of All Things is not a clear-cut tale of redemption and healing. It’s honest and messy and complicated (who else, after all, does Ross have to thank for her introduction to the outdoors but her abusive father figure?) and a disturbing, gripping read.

Outdoor ���ϳԹ��� Memoirs by Women: Sara Wheeler’s ‘Terra Incognita’

has been called “the first funny book about Antarctica,” and fair enough: Though Sara Wheeler writes about the generation of ice-bearded, cold-blackened men who froze and died in the first penetration of the continent, and even leans on the writing they left behind, her book has little in common with those dusty explorers’ tomes. It is funny, and thoughtful, and keenly aware of the intense oddity of the modern Antarctic experience, with its high-tech pods of labs and dorms at the end of a long, flimsy resupply chain, surrounded by the rawest, emptiest wilderness imaginable. In her seven months there, Wheeler hops from one isolated base camp to the next, each one maintained by a different nation—the Americans, the Italians, the Kiwis, the Brits. She gets drunk in an informal dorm-room speakeasy at McMurdo, pitches her tent in remote field camps, and ventures out onto the ice. Through it all, she captures the peculiar hold the polar regions—both north and south—seem to have on nearly everyone who travels them.

Outdoor ���ϳԹ��� Memoirs by Women: Beryl Markham’s ‘West With the Night’

Beryl Markham was Africa’s first licensed female pilot, and the first pilot of either gender to fly solo, east to west, across the North Atlantic. As if all that wasn’t accomplishment enough, the woman could write.

West With the Night is a memoir of her time spent flying out of Nairobi, landing on makeshift airstrips at hunting camps and threadbare mining settlements across eastern and central Africa, flying over the wild herds of the Serengeti, and of her later record-setting air exploits. It’s also the story of Markham’s rural Kenyan childhood, complete with a mauling by a half-tamed lion. Most of all, though, it’s about the experience of solitary bush flight itself. “To fly in unbroken darkness without even the cold companionship of a pair of ear-phones or the knowledge that somewhere ahead are lights and life and a well-marked airport is something more than just lonely,” Markham writes. “It is at times unreal to the point where the existence of other people seems not even a reasonable probability. The hills, the forests, the rocks, and the plains are one with the darkness, and the darkness is infinite. The earth is no more your planet than is a distant star.”

Outdoor ���ϳԹ��� Memoirs by Women: Martha Gellhorn’s ‘Travels With Myself and Another’

Martha Gellhorn was a globe-girdling war reporter, novelist, and travel writer. She was also the third wife of Ernest Hemingway, the “another” referred to in the . Papa shows up briefly in the book, referred to as U.C. (her “Unwilling Companion”—she recalls that after their arrival in Hawaii, he fumed, “I never had no Christed flowers around my neck before and the next son of a bitch who touches me I am going to cool him”), but really, it’s a memoir about Gellhorn’s solo travels, her “best horror journeys.”

The writing is spare and dry, laced with caustic humor. An account of Gellhorn’s first trip to Africa, a 1962 trek from Cameroon across the heart of the continent to Kenya, takes up half of the book. (Elsewhere, she sails the Caribbean in a local’s sloop, and hangs on a Red Sea beach with a group of hippie backpackers. “Like their bourgeois elders, who swap names of restaurants, they told each other where the hash was good,” Gellhorn writes. “It is impossible to escape a painful amount of dull conversation in this life but for sheer one-track dullness those kids took the cookie.”) Cranks have a long, proud history in travel writing—see: Theroux, Paul—but Gellhorn manages a neat trick: Even while she dwells on the worst of her misadventures, her love of exploration and discovery peers through. “No matter how horrendous the last journey we never give up hope for the next one,” she writes. “God knows why.”

Outdoor ���ϳԹ��� Memoirs by Women: Kira Salak’s ‘Four Corners’

Kira Salak was named for an Ayn Rand character, and raised in a cold, lonely household that valued strength and discouraged displays of vulnerability. When she left home, her travels became a series of increasingly harrowing challenges, all aimed at answering one question: Could she get herself out? Her journey up and down the length of Papua New Guinea as a solo 20-something, the subject of , was her riskiest trip yet.

Salak criss-crosses the PNG hinterland on foot and by boat, facing theft and extortion, illness and injury, murderous government operatives and armies of cockroaches along the way. The book is tense and packed with action, but it’s also deeply thoughtful: Why does she do the things she does? When will she stop pushing herself? Determined as she is to be tough, tougher than any man she encounters, Salak is also forced to confront the role gender plays in her travels. “Like it or not, my femaleness acts as a constant reminder that I’m stepping into an area where, even today, women aren’t often allowed,” she writes. “It’s hard to get cocky about any trip when I know that I carry along an additional liability most men can hardly fathom: the omnipresent possibility of rape. Sometimes I wonder where women might go, or what they might do, were it not for this fear holding them back.”