It’s clear by now that for women, “having it all”―where “it” encompasses children, a partner, hobbies, a healthy social life, and a thriving career―is a fantasy. This fantasy tends to be peddled by people who are either too naïve or too oblivious to recognize how only certain kinds of privilege make this possible.

It’s useful, then, to have frank memoirs from women trying to fold their families into their wanderlust and their passions. They might not always succeed. But these three new books show how worthwhile it is to view motherhood not as the death knell for an adventurous spirit, but as one adventure that might be compatible with others—if you can afford the compromises.

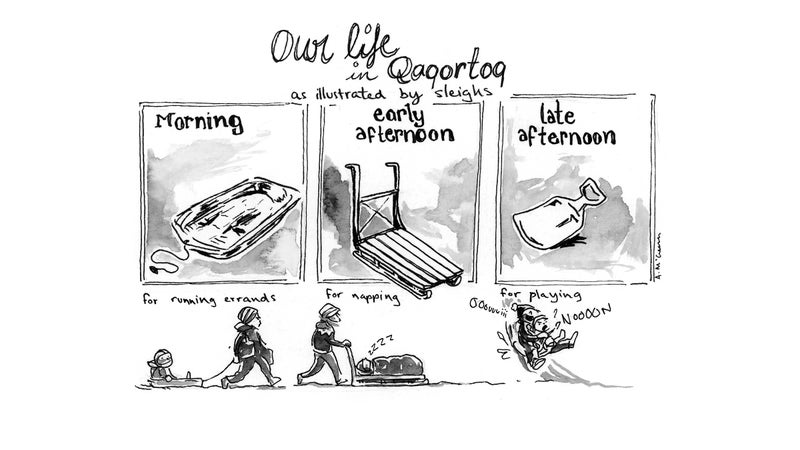

(Conundrum, $20) has an unusual format that reflects the tricky logistics of planning a family adventure. This travel narrative is told in daily postcards drawn and written by author Alison McCreesh, which relate a six-month journey she and her active young family take to places above the sixtieth parallel: from their home in Yellowknife, Canada to other northern parts of Greenland, Iceland, Finland, and Russia. McCreesh’s black-and-white drawings are simple but effective at capturing both the daily moments of life “north of 60” (like the elderly women in Lapua, Finland, travelling by scooter even in the heart of winter) and the stark beauty of these frozen parts (like the fjords of the Arctic Circle, inhabited by musk oxen).

Some financial resourcefulness is necessary to enable this trip of a lifetime. McCreesh applied for and was awarded artists’ residencies in the various destinations, and the trip was also partly funded through individual contributions of $20, in exchange for one of the postcards. She and her husband wanted to pull off the trip before their baby turned two, so that he could travel for free.

The complications of these logistics hint at the complications of domestic details overseas, which test McCreesh’s marriage and her work. She struggles with feeling like she’s spending too much time in art studio, while her husband struggles with being the main caregiver for their infant. Both partners are dissatisfied at points. And McCreesh’s niggling worries—about not enjoying the experience enough, about working too much or too little, about not spending enough time with her family—will feel familiar to many women juggling multiple roles and feeling not entirely successful in each. On New Year’s Day, 2017, McCreesh writes to a fellow Canadian: “I worry I missed out on the real experience of this residency. I worry I’m generally missing out on the real experience of life.”

Juli Berwald, the jellyfish-obsessed author of (Riverhead, $18), also travels to interesting places for work. Key for her—a mother of two who feels wistful about having left behind her career as an ocean scientist—is fitting research trips for her book into the rhythms of family life. So she uses her husband’s frequent-flier miles to book a trip to Japan, where she hunts for giant jellyfish. During family vacations on the Massachusetts coast, her husband and kids go mini-golfing while she visits a marine biology lab. And she turns a family trip to Israel, for her nephew’s bar mitzvah, into an opportunity to spot a jellyfish bloom. But this also becomes an opportunity to introduce her kids to snorkelling and snuba diving, and thus to share her passion for open waters. Clearly, having both a supportive partner and some financial security are key to making all this work.

Spineless is more science book than conventional memoir, with biology descriptions that sometimes verge on the tedious. But these can also be breathtaking, like the descriptions of the light show that bioluminescent sea creatures put on in the deep ocean. The book is also full of intriguing tidbits about the surprising power of jellyfish. For example, massive gatherings of jellyfish have caused power outages in several countries.

But apart from the many fun facts scattered throughout the book, what shines through this is Berwald’s fascination with her subject, and the way it transformed a woman feeling stuck in her life and craving a new purpose. “The jellyfish helped me dig down to a fire inside,” Berwald writes.

(Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, $23) is more somber than the other books. Author Melissa Stephenson has written elsewhere about using running as a kind of . Driven tackles a different trauma―the suicide of her brother―and a different movement-based coping mechanism―driving.

Driven is the story of Stephenson’s life, told through the cars in her life. As with some of her relationships, many of these are broken, and not all get repaired. Wanderlust is instilled in Stephenson from a young age, and cars both enable her spirit of adventure and allow her to get at intangible emotions while dealing with very tangible objects.

Her love of the open road also endangers her at times, like when she drives over the prairies between Montana and Indiana in a blizzard. In one sequence that’s alternately funny and horrifying, college student Stephenson drives from Montana to Alaska with a boy she’s lukewarm about, but whose VW camper van she adores. After they fight and split up, she’s left to hitchhike from Anchorage to Homer with a truck driver who gets increasingly creepy. After she kicks and threatens him, he agrees to let her drive the rest of the way. He even gives her some cash by way of apology.

But mostly, Driven is about family. Stephenson spends much of the book grappling with her old family having gone from four to three members after her brother’s death. But she reaches closure and contentment when her new family, after her divorce and her ex-husband’s departure from Montana, also morphs from four people to three—herself and her two kids. As she writes, in one of many moving passages, “We are complete, the three of us a unit I want finally to travel with, not run from, no sight in the world worth seeing unless we do it together.” By the end of the book she’s managed to incorporate her kids into her wanderlust, whether on cross-country road trips or on shorter camping trips, rather than just driving away.

These books don’t belong to the memoir adventure genre, but they’re part of a new crop of women’s memoirs detailing messy everyday realities through an outdoorsy lens. We need more stories like these from women with even more diverse circumstances (after all, McCreesh, Berwald, and Stephenson are all white North American women with male partners or ex-partners). In general, we need more stories from women like these three, who all crave new experiences and knowledge, and are frank about the compromises they have to make for their families. Together they provide a snapshot of how some creative, experience-seeking women are seeking not to “have it all,” but to “make it work”—even with a baby in tow.