Books: August 2011

The Invisible Man

Two new books clash over the disappearance of Everett Ruess

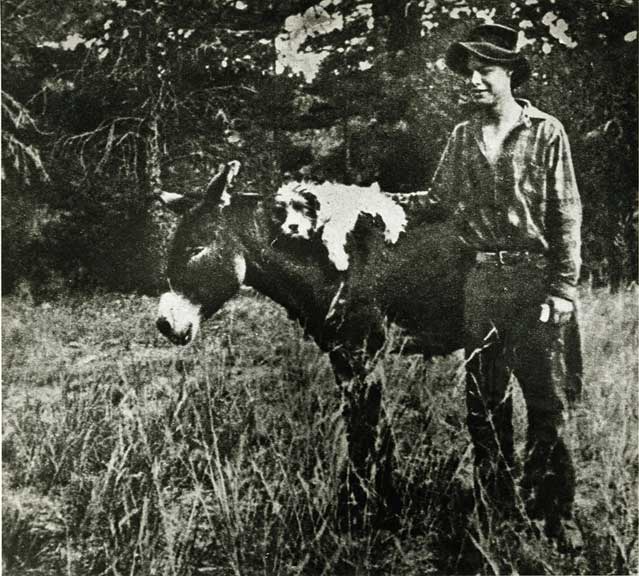

In November 1934, a 20-year-old poet and explorer named Everett Ruess hitched up two burros, walked into southern Utah‚Äôs canyonlands, and disappeared. In the ensuing 76 years, the myth of Ruess joined the likes of Amelia Earhart and D. B. Cooper. Some said he was murdered. Others suspected suicide. Wallace Stegner and Edward Abbey found his story irresistible; so did Jon Krakauer, whose 1996 classic noted the similarities between Ruess and Christopher McCandless. Finally, in 2009, the case seemed to break open: author David Roberts, a longtime ∫⁄¡œ≥‘πœÕ¯ contributor, announced that he had found what he believed to be Ruess‚Äôs remains on the Navajo reservation in Utah. National Geographic ∫⁄¡œ≥‘πœÕ¯, which had funded Roberts‚Äôs search, trumpeted an initial DNA test from the University of Colorado that appeared to confirm the identity. Huzzahs and fanfare ensued. And then ‚Ķ doubt crept in. Further DNA tests revealed that the bones likely ¬≠belonged to a Native American man. Backpedaling and blame ensued.

Now come the inevitable books. In (Broadway Books, $25), Roberts recounts the discovery and undiscovery in a gripping firsthand narrative. Meanwhile, historian Philip L. Fradkin takes a scholarly and skeptical view of both Ruess and Roberts in (University of California Press, $25). The books get along as well as two tomcats in a burlap sack.

Cards on the table: I admire some of Roberts‚Äôs books ( and ) and find others too hastily penned. Finding Everett Ruess is easily one of his best. Roberts‚Äôs excellent reporting establishes Escalante, Utah‚ÄîRuess‚Äôs final jumping-off point‚Äîas a town that knows more than it‚Äôs willing to tell. ‚ÄúTalking to residents, I felt that I had crept to the edge of some great secret that the town fiercely guarded,‚Äù he writes. Roberts posits that Ruess stumbled upon murderous cattle rustlers‚Äîand that a local omert√Ý keeps the truth buried to this day. ‚ÄúToo many of the folks that might be incriminated, they still got kids and family around,‚Äù one old-timer tells him.

In July 2008, a Navajo acquaintance led Roberts to a set of bones stuffed into a crevice about 100 miles from Ruess’s last known whereabouts. Anthropologists and DNA experts said the remains belonged to a male between the ages of 19 and 22, and the skull seemed to fit a photo of Ruess’s face. One DNA expert called it “an open-and-shut case.”

But after National Geographic ∫⁄¡œ≥‘πœÕ¯ announced the find, a prominent Utah archaeologist named Kevin Jones convinced the Ruess family to demand further DNA testing. Experts at the Armed Forces DNA Identification Laboratory found no match with Ruess‚Äôs familial descendants. The lab did, however, find close matches with three Native Americans.

“In our zeal to solve the mystery, we had dug up a Native American, probably a Navajo,” Roberts writes. “Any way you looked at it, that was a terrible desecration.” Here, the author leaves the reader wanting. Roberts had been searching for Ruess for more than a decade; the failure must have been crushing. Though he admits to shame and disappointment, he conveys little of either.

Perhaps he was already bracing for critics like Fradkin, whose Ruess book feels strangely off-key, written with the bitter tone of someone whose subject has been co-opted. He casts the mythologizing of Everett Ruess as a debasement of ‚Äúa youth who went to extremes ‚Ķ and burdened his parents with uncertainty and grief.‚Äù Fradkin accuses Roberts of using ‚Äúforced facts‚Äù and employing ‚Äúblind trust.‚Äù The 2009 demise of National Geographic ∫⁄¡œ≥‘πœÕ¯ is seen as karmic justice for the magazine‚Äôs sins against Ruess. What starts as a biography ends as an airing of grievances.

David Roberts’s Finding Everett Ruess is by far the better book, thoughtful and passionate. The author is no stranger to risk, and in this instance he ventured and lost. But he turned defeat into a compelling portrait of the Ruess myth, elevating our understanding of the West and its strange, deadly landscape and inhabitants. And Ruess? He’s still out there, his mystery growing with each retelling. “Everett,” one member of the Ruess family tells Roberts, “just doesn’t want to be found.”

Required Reading: August 2011

Mark Adams retraces the route of Hiram Bingham III, and debates whether he was a pioneer or a looter, in Turn Right at Machu Picchu: Rediscovering the Lost City One Step at a Time (Dutton, $27). And in The Ledge: An ∫⁄¡œ≥‘πœÕ¯ Story of Friendship and Survival on Mount Rainier (Ballantine, $26), mountaineer Jim Davidson and coauthor Kevin Vaughan relive the 1992 crevasse fall that killed Davidson‚Äôs partner.