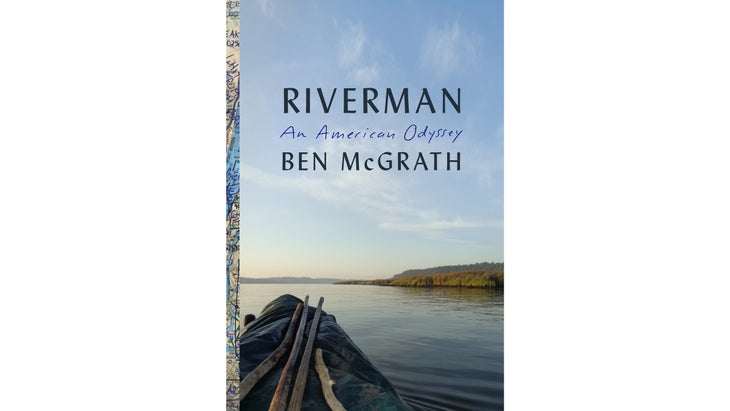

The cover shot of —a wide stretch of the Hudson River—was taken not far from Piermont, New York, where the book’s author, Ben McGrath, lives with his wife and two young children. “It would take me half an hour to be in that same spot,” McGrath says. He often does paddle there, putting in right in front of his house. “I get up before the kids wake up, and go out on the river in my kayak,” he says. “It’s so beautiful.”

In early September 2014, another boater meandered past McGrath’s neighborhood: Dick Conant, a 63-year-old guy in old overalls, steering an overstuffed canoe. He tied up his boat the seawall in front of McGrath’s neighbor’s house and was invited in by the neighbor who was in the middle of celebrating his birthday with some guests, including McGrath. That’s where he first met Conant and learned of his plans to paddle all the way to Florida. McGrath, a New Yorker staff writer, ended up writing about Conant, who had paddled thousands of miles on the nation’s rivers over the years, tracing a watery course through tributaries, major waterways, and small towns along the way.

Nearly three months later, McGrath received a phone call from a wildlife ranger in North Carolina. A red canoe had been discovered overturned in Albemarle Sound, and its owner was nowhere to be found. Among the boat’s many contents was a piece of paper with McGrath’s phone number scribbled on it. McGrath decided to look into Conant’s disappearance, and what he discovered instead was the story of an itinerant life of adventure that seemed at once inspiring, sad, and almost impossible in modern-day America.

The resulting book is an instant addition to the canon of literature on eccentric wanderers seeking meaning in the outdoors. We chose it as the April pick for , and to wrap up our discussion, I spoke with McGrath about the legend of Dick Conant and his ultimate fate.

���ϳԹ���: You write in Riverman that you moved up to the Hudson from New York City to connect with your youthful escapism and find your watery part of the world. Where did your affinity for that come from?

McGrath: I grew up in suburban New Jersey, which is about as non-adventurous a place as you can be. But we had a wetland, a sort of birding sanctuary, behind our house that was 150 acres or so—big enough for me to feel like I was, in my own mind, going Daniel Boone back there. It was a place of freedom. My best friend and I would go walking to what’s called a lake but was really more of a bog. We did once get an inflatable boat and launch it. We made it across to the other side before the marsh warden said no boats allowed.

I hate that there was a marsh warden.

Yeah, my attempts to explore that bog were kind of curtailed, but in our twenties, my friend and I did go on a ten-day canoe trip in the Florida Everglades together, which in retrospect is probably the longest time in the past 25 years I’ve gone without checking my email. Part of what I envied in Dick Conant was his ability to drop out like that.

As a former magazine editor, I was struck by something you said early in the book—that if you’d heard about Conant in a press release, you probably would’ve ignored it. I’d feel the same way; you can get pretty jaded about those kinds of emails. Why do you think we tend to discount official adventure pitches?

Maybe there have always been people trying to call attention to themselves, but the digital age has made it easy for people to act as though they’ve got a whole promotional apparatus behind them. It’s easy for a lone wanderer to create his own stationary and make a press release and make it seem like he’s backed by the North Face or something. On some level, I tend to assume they’re doing it for the attention rather than the genuine urge to travel.

Conant is the opposite of that pixelated personality.

For sure. You had to talk to him to understand why he was different. You would immediately get that there was something legitimate about this guy. But then when you tried describing him to someone else—Hey, this guy just paddled past my house on his way to Florida!—two-thirds of them were like, Something seems off.

In Bozeman, Montana, where Conant sometimes lived in a lean-to he called the Swamp, people tended to describe him more like a vagrant. But on the river, he was Huck Finn or Forrest Gump or Christopher McCandless. I see the Forrest Gump connection: both represent a very innocent America, full of generosity and kindness. But at the same time, Conant has a Princeton Magazine interview with Paul Krugman in his canoe, and he spends his gambling winnings on The Journals of Lewis and Clark.

When I think about Forrest Gump, he keeps landing at these important moments in American history and interacting with prominent people in spite of being an aw-shucks nobody. That turned out to be true of Conant, too. There’s a moment in the book where he goes to Woodstock and Jimi Hendrix locks eyes with him and tells him, “Hey man, keep the Pope off the moon.” Everyone who grew up with him thought it was totally natural that, of all their friends, of course Dicky would be the one who interacted with Hendrix. So he did have a Forrest Gump way of being on the margins and yet right at the center of history at the same time.

So many people you talked with said that being with him reminded them of dreams they once had, of lighting out on a river or having that sense of freedom.

Totally. People projected things onto him in that way. They sort of imagined their version of him. One of the most interesting things about him is that, across the political spectrum, he was a kindred spirit to super-right-wingers and super-lefty hippies at the same time. They all thought he was their guy.

Another comparison that comes up is Christopher McCandless,��from Jon Krakauer’s book Into the Wild. To me they seem a little different—Conant appeared to relish the society of other people, even as he ran away from society with the capital S. Whereas McCandless seemed to want to explore his own solo survival.

The first time that comparison was put to me was after I wrote my initial Talk of the Town story about Dick. I got a letter from a reader saying, “He reminds me not only of Forrest Gump, but of Chris McCandless.” At that point, Dick hadn’t disappeared yet. So that turned out to be prescient. And repeatedly, people would make that comparison.

To me, the main difference is their age—there’s about 40 years separating them. Chris McCandless died in his early twenties, and when I met Dick Conant, he was 63. But they both were successful, smart people who weren’t marginal characters as young people. What’s most compelling to me about Chris McCandless is the effect he had on the other people who met him. He was losing his faith in society with a capital S and going farther and farther out into the bush. But all the people who met him remembered him powerfully. What validated Dick as a character to me was the same thing that validated McCandless as a character, which is to say that he had a positive, powerful effect on everyone he met.

But I think because Dick was older, he had come to realize what he prized in life. He would meet young people in coffee shops who would speak with idealism about what’s pure and what’s not, and he would laugh and say, Oh, you’re young—you’ve got a lot of life in front of you. So by the time I met Dick, he had figured out that what he needed in his life was a healthy mix of nature on his own and then friends. And he found friends on the rivers. Had you met Chris McCandless at age 60, had he survived, that same thing might have been true.

Let’s talk a little bit about your writing the book. One acquaintance of Conant’s tells you, “Look, if you have his journals and you can’t make a book out of it, then you’re in trouble, dude.” Give us a sense of how much material you had.

So there are thousands of photographs—just the memory cards to his digital camera on his last trip, I think, had 4,400 photographs. Then in the storage lockers, there were hundreds of photographs from old Polaroids and thousands of slides I never even got around to looking at. There were maps by the hundreds, if not thousands, and marble composition books, separate from his 2,000 pages of typed manuscript-style journals. There were diaries of his life in the Bozeman Swamp, essays and short stories that he wrote in college, studying art, or in his twenties, working at a hospital. There were folders of files from his time in the Navy, including from a tribunal about his mental health, and questionnaires that he filled out while seeking alcohol treatment after getting a DUI in Wyoming in the 1970s. And there were receipts by the thousands, bundled up and organized with rubber bands. Even his canoe was full of receipts.

What was the weirdest thing in his canoe?

There were like 17 toothbrushes.

When you have that amount of material, how do you begin to put it together into a book?

This was the challenge—and also what was appealing to me about the project. I’d been doing a fair amount of sports journalism at The New Yorker, where you’re getting extremely limited amounts of time with famous people and lots of layers of handling. This was the exact opposite of that—full access to the inside of an entire human being. But you have to try much harder to think about what to include. It was easy to get lost in this stuff. Because I had met Dick and knew him to be an amazing person, I could just be endlessly fascinated. For example, he had all these calendars, and my wife had to remind me, Do you really need to see what he did in October of that year, as opposed to in November?

When was the last time you talked with Conant himself?

I got an email from him a month and a half after we met, in October 2014, saying, I read your article, good job. He was in Delaware at that point. And that’s the last communication I had. Then, a month and a half later, I get a phone call from a park ranger in North Carolina saying they’re investigating a missing boater.

Has any new evidence come up about his disappearance since you finished the book?

Nothing. I’m going down to North Carolina to the scene of his disappearance in a few weeks, and I’ll be curious to hear what else they’ve learned. Every so often I’ll get an email from someone who says, I think I met him. And they’ll send me a picture, and it isn’t him.

So he kind of lives on, paddling the rivers out there?

He does. He lives on in people’s minds. Definitely there are people who prefer—or choose, depending on how you look at it—to think that he is continuing to do his thing. On some level, what matters is that you believe that it’s possible. And the actual fact is sort of secondary.

To me, that sense of possibility was always what was most powerful about his story. So much of it seemed implausible, yet all of it was true. So the overall experience of immersing yourself in Dick Conant’s life story was of just being amazed at how much more is possible than you are willing to grant.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.