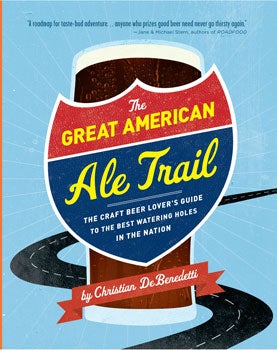

This month, self-described beer nerd and ���ϳԹ��� correspondent releases his new book, (Running Press, $20, ). The book is one part American beer history, one part review guide, and two parts brew-inspired travelogue, chronicling DeBenedetti’s reporting forays to breweries across the U.S. It’s also the perfect road-trip companion for beer lovers—second only, perhaps, to a designated driver. We caught up with DeBenedetti, who scored a prestigious Watson grant in 1996 to study the world’s beers and brewing techniques, to find out the roots of his beer fanaticism, what his favorite beer is, and the best American road trips to take this with a great brew as the goal.

��

OUTSIDE: When did you first become interested in beer?

DeBenedetti: It started when I was a freshman in college. The guy who was supposed to be my roommate didn’t show up, and the school didn’t make me move, so I turned the other half of my dorm room into a mini brewery and the dorm lounge into my brewpub.

��

That must have been popular.

The idea was popular, and then people tried my first beer. I’ll never forget handing out the bottles, filled with pride and expectation. I had glued beautiful hand-drawn labels on each one. Everyone took a taste, and my friend Lincoln just turned and spat it out as far as he possibly could off the porch. He was like, “Good God, what is this?” I got better.

��

And eventually you got the Watson grant to travel the world studying beer. How long was it?

It was a 12-month trip that started in England. I eventually hit 14 countries and 59 breweries throughout Europe and West Africa, where I was studying rural brewing methods that used millet and sorghum instead of barley. In Europe, I lived in an 1800s brewing tower, camped in hop fields, apprenticed in the oldest commercial English brewery (Shepherd Neame), and basically wandered all over Belgium, Holland, Germany, and the Czech Republic with a backpack, a guitar, and a journal.

��

How many beers did you drink?

Well, I tried about 350 or 400 new beers, but I wasn’t trying to hit some land-speed record. For me it was about wandering from place to place and meeting these individuals, seeing who would take me in and give me a little job to do and maybe let me stay at the brewery. It was incredibly exciting, and it totally changed my life.

��

You traveled pretty extensively for this book, too. How many places in the U.S. did you get to?

The book is composed of beer travels that I’ve done over the past, say, ten years. I’ve always been the kind of guy who wants to pull over at a brewery when I see one. But over the past year or so, I set out to cover as much of the new American craft-beer culture as I could, and I managed to hit more than 20 states.

��

What were some of the highlights from the year on the road?

Well, for one I went to Anchorage in mid-January. It was minus 15 degrees. Most people were like, “Why the hell would you go to Alaska in mid-January,” and frankly the answer is “For good beer.” I made my way down to Juneau to visit the Alaskan Brewery and ended up going powder skiing with one of the brewery employees on Douglas Island, a snowy tidal island in the Gastineau Channel, and serving as a mock avalanche victim for Geoff and Marcy Larson, who are the founders of Alaskan Brewing and who volunteer training recovery dogs. The beer tasted especially perfect that day.

��

What was the most surprising thing about researching the book?

Just how widespread great beer culture is in the U.S. It’s literally in every part of the country. One of the happiest days I had was driving across Lake Pontchartrain, in Louisiana, from New Orleans up to Covington, where I was going to visit Abita Brewing Company and Heiner Brau. There were these heavy stormy skies. And as if on cue, the Allman Brothers were blasting on the radio, “Statesboro Blues.” I’d never been to Louisiana before, much less the rural parts north and outside of Covington, and I ended up having one of the best days of the trip. It was a huge surprise to me to find such a vibrant craft-beer culture in Louisiana. It was such a treat.

��

In the book, you mention that the U.S. is in the midst, and has been for some time, of a renaissance in beer culture. How did that start?

I could go on for days pinpointing people and places where it took hold, but the gist is that it was in Northern California and in Oregon around the late seventies, when American breweries had really vanished to the point where there were just about 40 or 50 breweries in the entire United States. You had scores of pioneering people who tasted beer in Europe and who learned to home-brew. One of those people was Ken Grossman of Sierra Nevada, which is now one of the two or three largest craft breweries in the United States. You also had people like Bill Owens, who started Buffalo Bill’s Tavern in Hayward, California; the Widmer brothers of Portland; and the Red Hook story up in Seattle. Now we have 1,800 breweries and brewpubs, with an estimated 700 in planning stages across the country. Even so, that’s less than the 4,000 breweries a much smaller America supported in 1872. It was—and is—a genuine movement.

��

Come up with a favorite beer over that time?

The stock answer is “My next beer,” because there are so many new ones coming out almost every day. I was literally sitting at a beer bar last night with some friends, and when I looked at the list I realized I hadn’t tried 90 percent of the beers on it. I live near Portland, and I go to beer bars practically every day. That’s how fast it’s changing.

��

Give me your favorite beer at the moment then.

I’d probably say the whole family of traditional farmhouse ales, beers that originally came out of southern Belgium. They hit that sweet spot of alcohol percentage and yeastiness and spice and character. Now American craft brewers are pulling off incredible variations of these styles, even some aged in oak barrels. Some of the best are coming out of Oregon’s Logsdon Farmhouse, Baltimore’s Stillwater, and Hill Farmstead of Vermont. Also, there’s nothing better than a good pilsner on a hot day.

��

You may not believe it, but I worked at a brewpub for two years, and over the course of it I developed a hops allergy, meaning I can’t drink beer.

You poor, poor man. What you need to do is look into the new batch of hopless beers. This is a new craft-brewing trend that goes back to the Middle Ages. Before that, all beer was unhopped and spiced with other herbs, and a lot of home brewers and craft brewers have been rediscovering the traditions. I just tasted one from Gilgamesh brewery near Salem, Oregon, and the beer is called Mamba. Instead of hops, it’s spiced with black tea and orange peel. Man, it’s delicious. You can drink it like Lipton all night long.

��

Sounds great.

Other breweries are experimenting beyond hops, too. Captain Cook used to spice his beers with spruce tips. He’d come ashore when he was exploring the Pacific Northwest to gather spruce tips and then home-brew on the boats with it. It became the inspiration for Alaskan Brewing Company’s Winter Ale. They use spruce tips—in addition to hops, unfortunately for you—to give it a spicy backbone.

��

Do you ever get tired of knowing so much about beer?

It’s a blessing and a curse. People ask me a question about beer and I could go on for an hour. But I did get to write a book about it. And the fact is, I am still learning, too.

��

What do you hope people will take away from the book?

I hope they get truly inspired to explore. And I hope that when people open up this book and don’t see their favorite beer or brewery, it’s not because it’s not worthwhile. It’s because this book is meant to be a starting point, not an encyclopedia. The most important thing is to get out there and start trying new things in new places. You should try as many as you can, because you just might find the best beer of your life.

��

Five Roadtrip-Worthy Craft-Beer Spots (as excerpted from The Great American Ale Trail)

MARSHALL WHARF BREWING

OURAYLE HOUSE BREWERY

LOGSDON ORGANIC FARMHOUSE ALES

DOGFISH HEAD BREWINGS AND EATS

LITTLE YEOMAN BREWING

Marshall Wharf Brewing

2 Pinchy Lane, Belfast, Maine

207-338-1707;

Established: 2003 (bar) and 2007 (brewery)

Located right on the pier next to the tugs of Belfast—a fishing village first settled in 1770—the Marshall Wharf brewery was built in the town’s original granary in 2007. A combination patio- and bocce-court-equipped beer bar, seven-barrel brewhouse with eight-spigot taproom, lobster pound (so you can buy some fresh-caught on fall mornings to take home), and a 12-tap seasonal beer garden, Marshall Wharf is truly a one-stop affair.

Order Up: Cant Dog Imperial IPA

Ourayle House Brewery

215 7th Ave., Ouray, Colorado

970-903-1824;

Established: 2005

In the home of North America’s premiere ice-climbing festival, Ourayle House is marked by a mangled whitewater kayak hanging on a makeshift fence. Inside, this “one man, one dog” operation is festooned with discarded ice axes, crampons, and carabiners hanging willy-nilly on the split-and-varnished salvaged-timber walls. A woodstove crackles in one end of the room. In short, this is a little slice of heaven.

Order Up: The mild and mellow Biscuit Amber

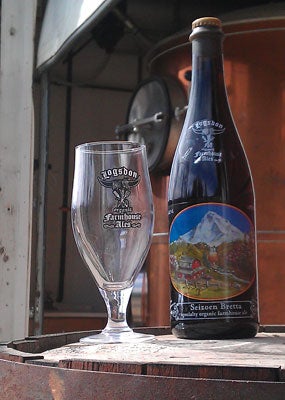

Logsdon Organic Farmhouse Ales

Logsdon Farmhouse Ales

Logsdon Farmhouse Ales’ big red barn

Logsdon Farmhouse Ales’ big red barn785 Booth Hill Rd., Hood River, Oregon

541-490-9161;

Established: 2011

Founder and longtime brewing-industry veteran Dave Logsdon just opened this brewery on his family’s beautiful working farm outside of Hood River, complete with a big red barn (where the kettles, tanks, and barrels live), pets, horses, and highland cattle. About eight miles from the north face of Mount Hood (with incredible views of the peak’s 360-foot-thick Eliot Glacier) and the sail-sports mecca of the Hood River Gorge, it’s one of America’s most picturesque breweries.

Order Up: Seizoen Bretta, a malty, yeasty saison with an addition of Brettanomyces yeast adding fruitiness, acidity, and woody, earthy, almost leathery notes

Dogfish Head Brewings And Eats

320 Rehoboth Ave., Rehoboth Beach, Delaware

302-226-2739;

Established: 1995

Sam Calagione’s Dogfish Head beers (and Discovery Channel show) have inspired legions of fans. A coast-drive road trip to his original two-story Dogfish Head location in the center of Rehoboth Beach makes for an excellent pilgrimage. There are always more than 20 Dogfish brews and a cask (including pub-only drafts). There’s also a micro-distillery project gathering steam on-site, solid pub grub, and live music.

Order Up: Punkin Ale, a delicious fall seasonal of 7 percent alcohol that will make you reconsider beers made with the orange veggies

Little Yeoman Brewing

12581 Dallas Lane, Cabool, Missouri

417-926-9185

An hour and a half drive south of Springfield on a leafy farm in the Ozarks, Little Yeoman is a minuscule 80-gallon brewery with big dreams. For now, the only way to try the beers is to drive out to the middle of the Mark Twain National Forest, look for a converted-keg mailbox, and pay a visit. There, in a modest two-room barn, Chad Frederick (whose commute to work is a short walk through the woods) has made many fans who make regular return visits, sometimes camping on the grounds, gathering around a woodstove, and sipping from homemade ceramic mugs.

Order Up: the popular, medium-bodied Porter