has climbed, guided, and written about first ascents from Peru to the Himalayas. In 2007, he was awarded the Robert Hicks Bates Award for outstanding skill, character, and promise as a young climber by the American Alpine Club. Through his experience guiding in big mountains, the 31 year old has come to realize that the client’s experience of a situation is often very different from that of the guide. With this in mind, Wilkinson became fascinated by the differing personal accounts of the 2008 K2 tragedy, in which eleven mountaineers died in the deadliest period in the mountain’s history. His book about the disaster,, is a finalist at this week’s . We caught up with him on his iPhone after a day spent climbing off the Kancamagus Highway in the White Mountains of New Hampshire.

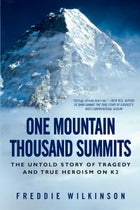

One Mountain Thousand Summits

One Mountain Thousand Summits

One Mountain Thousand SummitsNew Hampshire?

When I was in college [in Hanover], I totally assumed that I would move out West. New Hampshire just kind of stuck with me. Even though the mountains are a little smaller, there is so much diversity of year-round adventure. I think it’s really underappreciated. If you live in Jackson Hole—the Tetons are amazing, but you need an 18-hour day to access them. New Hampshire has adventures that you can fit into the rest of your life, and the community’s a little smaller. I like the fact that climbing is sort of a fringe sport. You go to Boulder, Colorado and everybody’s a climber. I love being kind of a freak.

What drew you to write about K2 in One Mountain, Thousand Summits?

For better or worse, those mountains are lightning rods for issues that come up in our community and in the sport of climbing. The greater public makes a lot of assumptions, and their main access is through headlines. When this tragedy happened in 2008 [A Few False Moves, ���ϳԹ���], I wanted to make sure that there were voices that were informed about climbing and could offer a deeper understanding of what’s going on out there.

How did you find your in?

I stumbled onto the story of the Nepalese Sherpas who were on the mountain. I was really interested in that because I worked as a guide all though my 20s on big mountains like Denali, and I immediately felt that these Sherpas were really serving in the role of a guide. From my own experience I know that very often the story told by the client is really different from what the guide sees with his perspective. So I had this instinct, like, wow, those Sherpas—those are the people I want to interview.

What did you uncover?

In a lot of the early stories that came out about the tragedy, it was portrayed as this . It was this every-man-for-himself event: and then, One thing went wrong, and chaos ensued, if I could paraphrase massively.

Talking to the Sherpas—in my opinion, they were the total heroes. They did try to organize people to go back up the day after summit day and look for survivors. There were some amazing feats of heroism. Not to introduce racial politics into a hugely unfortunate event, but I think if it had been a Western Climber or a European climber, who had made the same effort and done the same feat, we’d be hearing about it: It would be on the cover of ���ϳԹ���. But, for Sherpas, that’s all in a day’s work, and we need to acknowledge what they’re doing. Even though the tragedy was terrible, I found a bit of an uplifting story. Through their efforts, it was obvious that the mountaineering ethic isn’t totally dead.

Is that an important part of telling this story?

There’s so much negative press about mountaineering these days, and high altitude climbing in particular: that it’s been corrupted and that it’s a game for rich posers. That’s partly true, but there’s a lot more to it than that.

The 2008 K2 tragedy is kind of like a Rorschach Test: There were so many different facets to it, that, when you look into as a story, people will come to the conclusion that they’re looking for.

, an Irishman, very likely could have survived had he not stayed and tried to rescue these Korean climbers who were stricken after a fall. Ultimately, they didn’t survive, so the story of his sacrifice and his heroism wasn’t going to be recorded if somebody didn’t do a little more digging.

A lot of writing about climbing tragedies seems to be focused on the awe-factor—the scale of a disaster. You seem to be most concerned about these individual acts of courage. There were all these little anecdotes of people doing to the right thing. I wanted to make sure those were recorded, because I believe in feedback loops. When I was a kid, climbing stories were what inspired me. If we only write these pessimistic stories about how climbing has gone to hell in a hand-basket, that’s not setting the bar very high for the ethical standards we should all try to live up to. So I wanted to write a story that sets the bar high, to hopefully provide other climbers with something to think about the next time they’re on a mountain and they’re faced with a similar situation.

What writers do you read?

Probably my favorite writers are not climbing writers. A few books that were really influential to me while I was writing One Mountain, Thousand Summits: Solo Faces, by James Salter; Young Men in Fire, by Norman Maclean. (That book maybe more than any other book had an influence in how I developed the structure.) Hell’s Angels, by Hunter Thompson; The Right Stuff, by Tom Wolfe. In terms of climbing writers, is totally top dog. He’s a friend of mine—he’s kind of a mentor.

What does a mentorship with David Roberts look like?

You send in your writing, and he tells you it sucks. You’re dutifully humbled, but then you listen very carefully to what he has to say, and you learn a lot. David’s a total old curmudgeon. I sent him a manuscript of my book, and he was like, ‘Yeah, you fucked it up.’ And I think part of him did want to see if I could take it, because, being a writer, you have to have a thick skin. So I think there was a little bit of a hazing element there. But then I was reading a collection of interviews called The New NEW Journalists, and Krakauer was in there, and he said, David Roberts was a mentor: He always hated my writing and told me it sucked. And I read that, and I was like, Phew! Thank God.

You’ll be on a panel with David Roberts this week. What are you looking forward to most at Banff?

Oh, boy—I’m looking forward to connecting with the younger generation of storytellers, who are basically my peers, like my buddy , or . I think it’s kind of exciting— I’m 31 now, and my own generation of creative voices has really emerged, and I think the films and movies and books that are going to come out of adventuring in the next 10 years are going to be totally badass.