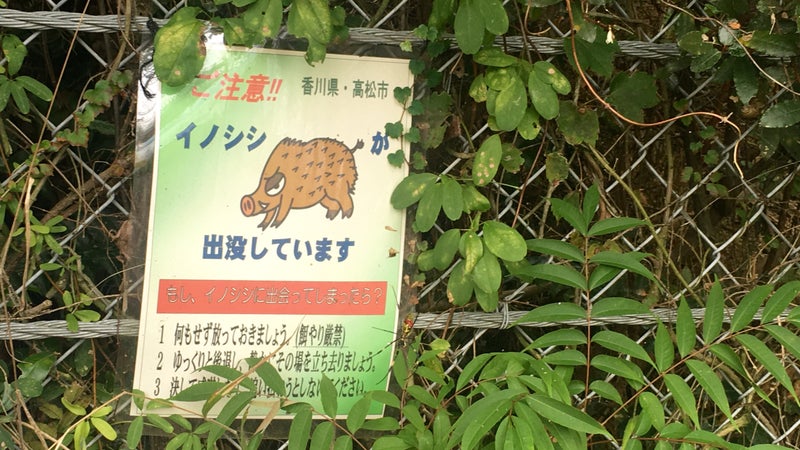

If you want to strike fear into the heart of a Japanese farmer, just utter these two words: wild boar.

The aggressive, hard-headed animals are some of the most destructive in the world, not only devouring crops, but destroying fields and root systems with their sharp teeth and trowel-like hooves from Kobe to Chiba City.

It wasn't always like this. Boars are a native species in Japan, but��you could go years without��seeing one there for most of the 20th century,��thanks to diseases like cholera��in the 1920s. Then,��in the early 2000s, the animals began descending on��cities and farmland in an almost plague-like fashion.��

Animals near Fukushima��are now radioactive—and journeying into nearby prefectures. Eradication is at red-alert levels.

Many believe this resurgence��was the result of human laziness: farmers and hunters allowed domesticated pigs to escape, then breed with their feral counterparts and��produce legions of hybrid boar-pig��offspring in the wild. Others blame a lack of food in the mountains, or expanding cities and roadways that have disrupted the natural boar habitat, leaving them no choice but to head into human territory. It doesn’t help that the boars have essentially no natural predators.

Whatever the cause, there are two��thing people can agree on: they’re ruthless, and they're everywhere.��

And sometimes, they're radioactive. In the contaminated area in and around the site of Fukishima’s 2011 nuclear meltdown, the boars' voracious appetite and prolific breeding has led to an��(thousands? Tens of thousands?) becoming contaminated with ��radiation.��Many of them are journeying��into nearby prefectures. People have even stopped eating a kind of boar stew that used to be a specialty dish in some of these places, for fear of radiation contamination. The impetus for eradication is at red-alert levels.

“I’ve used a lot of tools to fight against boars, but a lot of them have failed,” says Hideki Fukuhara, a loquat farmer in the city of Minamiboso. Fukuhara's orchards are far away from the radioactive hogs, but the damage to his crops is no less alarming as we examine the hoof marks on some of his plants that were recently victimized by boars. One of the youngest farmers in this lush, mountainous area of the Chiba prefecture, Fukuhara notes that many of his older comrades have simply given up on attempting to save their fields with a sigh of resignation: Those animals are too aggressive to be stopped.

Since no set national policy for wild boar control exists, protecting produce from wild boars has become something of a trial-by-error practice—and cottage industry—across the country.

Upstart��companies are creating spicy products like “pepper pellets” to scatter around plants that the boars will accidentally ingest, or strands of pepper-laced netting to be used as fences. (Boars like chewing fences but do not like hot sauce.) Some prefectures are cutting down grasses and trees to eliminate the boars’ hiding places. Fukuhara remains optimistic about the electric fences he’s erected around a fledgling grouping of loquat trees. Boars tend to lead with their noses as a primary sensory device, and it’s that tiny swatch of tender flesh that’s most likely to run into the fence. Zap. ��

Perhaps more important than simply protecting crops from boars is eradicating the boars themselves. Farmers know that in order to save plants and profits, something more drastic must be done—especially in the radioactive locations.

Japanese farmers and hunters use three primary methods to capture wild boars: box traps, wire traps and (the most controversial) hunting. Box traps function like giant, barred cages, luring in boars with a fly-infested, rice-covered habitat, then locking them in once a tripwire is kicked. Wire traps wrap around the feet of wild boars as they walk through the forest, then capture them by flipping the animal upside-down,��Looney��Tunes-style, so they can’t break away.

Hunting is the most effective means of control, though guns are not totally supported or widespread. “Something that complicates wild boar management in Japan is the exceptionally restrictive ownership, use, and access to firearms. This includes not only the general populace, but also with researchers, wildlife biologists, and natural resource managers,” says Mark Smith, a forestry and wildlife professor at Auburn University. In 2013, Dr. Smith joined an international team of wild pig experts to help tackle the increasing problem of boars invading urban areas within Western Japan’s Kobe Prefecture.

��“Although [recreational] hunting does occur in Japan, it is very limited,” says Smith,��“and hunter numbers are declining by the year, so there are fewer and fewer hunters out there harvesting wild boar.”

In the Chiba Prefecture, 5,900 hunting licenses (including firearms, wire traps, and box traps) have been issued to date, while in the more northern Myagi Prefecture, 1,876 licensed hunters brought in a whopping 4,964 boars in 2015. Government officials in Myagi, which borders Fukushima, have��seen increasing public support for hunting boars since 2011, but that stance is less popular in the rest of Japan.��

“After hunters bring in the boars, we help them test to see if they are radioactive,” says Mr. Satoshi Kimura, a government official from the adjacent Myagi Prefecture. “If the levels are too high, you can’t eat them.”��

Culinary woes aside, post-capture nuclear pig��disposal is much more complicated. Burying boars in mass graves—a common practice in most places—is too risky to the soil and groundwater when they’re radioactive. In response, in March 2016, government officials constructed the first-ever incineration facility specifically for wild boars in Fukushima, just outside the town of Soma. Most of the hogs headed for the fire have at least marginal levels of radiation.

One morning, I visited the relatively small incinerator, where a handful of men in haz-mat suits and protective eyewear showed me how the system works. We toured��the ice-cold meat locker that holds stacks of wild boar carcasses, then headed to the burn room itself, which fires up at a hog-annihilating 1,771 degrees Fahrenheit. When the boar’s remains come out the other side of the incinerator, any leftover bone chunks are whacked into smaller bits with a wooden mallet, then placed in protective containers. The entire operation, using a series of air filters and closed-loop systems, is said to be safe��for workers and the surrounding community—though I still had my doubts as the radioactive boar ash blew towards my face.

Despite increased concern about boars (radioactive and not), problems persist across the country��in large part because��many urban-dwellers think wild boars are downright cute.��Dr. Smith points to a current debacle��in the city of Kobe. Boars are now traveling into towns from the nearby mountains, getting stuck in concrete aqueducts, then reproducing in the waterways. One of the reasons the boars there are thriving? Townspeople are feeding them.

“What a lot of the people think is that the pigs are coming into the city because there’s no food in the forest, but that’s not true,” says Dr. Smith, who likens it to bears being fed on campgrounds across the U.S. “They’re coming down because it’s another easy food source. They are the most adaptable animals that you’ll ever find: we call them the ‘opportunistic omnivore.’ A pile of trash is a lot easier than rooting for nuts. They’re saying, ‘By gosh, I’m going to take the easy route.’”

Boars are a prime example of the increasingly complicated relationship between wildlife and human populations across Japan, with no good solution in sight. “We need to teach people how to be responsible when it comes to these animals,” Dr. Smith says, taking a long pause, “and what can happen if they’re not.”

The author is reporting from Japan through a program sponsored by the International Center for Journalists and funded by the U.S.-Japan Foundation.