Summer isn't just for easy beach reads. Pick up any one of these intelligently written books for a change; you won't be able to put it down.

- Alaskan Travels: Far-Flung Tales of Love and ║┌┴¤│ď╣¤═°

- A Sense of Direction: Pilgrimage for the Restless and the Hopeful

- Private Empire: ExxonMobil and American Power

- The Eskimo and the Oil Man: The Battle at the Top of the World for America's Future

- When Captain Flint Was Still a Good Man

- Canada

Hot Reads for Summer 2012: Road Warriors

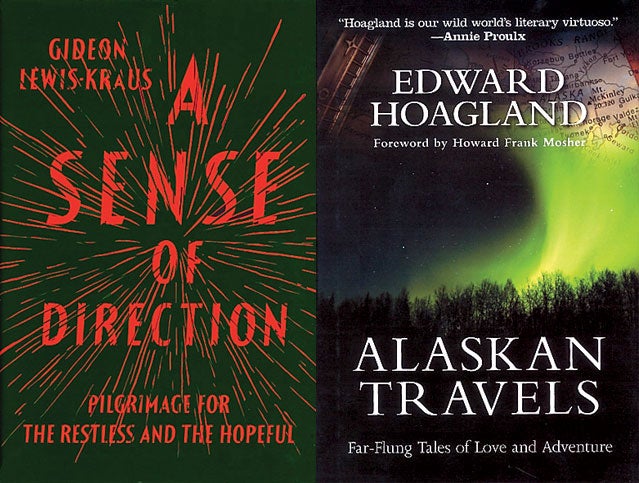

An old master and a new voice add to the travel-lit canon

From to , lighting out for the territory is a time-honored tradition in American literatureÔÇöthe writer setting off into a boundless landscape as backdrop for an inner quest of self-discovery. Few have mined that vein as deeply as Edward Hoagland. At 79, he is the author of some 20 books spanning a half-century of wandering. His latest, (Skyhorse, $23), is a hauntingly lyrical look back at a joint midlife love affairÔÇöwith both the ÔÇťnational dreamscapeÔÇŁ of 1980s Alaska and the sensual public-health nurse who drew him there. HoaglandÔÇÖs pre-Palin┬áAlaska is ÔÇťa destination created out of anger and quests,ÔÇŁ full of outcasts and fortune seekers mixing with an indigenous population struggling against a fast-changing world. Fur-trapping hippies, boomtown realtors, jail-breaking┬áEskimos, amputee Vietnam vets on snowmobilesÔÇöHoagland gathers their stories as if laying in stores against the Arctic winter. He tries to understand what has drawn them allÔÇöhimself foremostÔÇöto fall for a land of ÔÇťentrenched savageriesÔÇŁ so harsh that ÔÇťthe very snow emitted strange, pained, squeaky sounds underfoot, as if suffering too.ÔÇŁ This is Alaska before the stateÔÇÖs frontier spirit became a pop-cultural product. The result is too dark and sharply etched to be nostalgic, but it manages to bear the sadness of a vanishing place on every page.┬á

For a younger generation of writers, raised in a world circumscribed by and , the existential allure of travel still holds, but its rewards seem more fleeting than ever. In (Riverhead, $27), essayist Gideon Lewis-Kraus finds himself mired in a postcollegiate bohemian haze of art parties and dive bars in Berlin. Tortured by his absolute, paralyzing freedom, he and a friendÔÇö║┌┴¤│ď╣¤═° contributor Tom BissellÔÇömake a fateful (read:┬áinebriated) decision to walk the 500-mile pilgrimage route of SpainÔÇÖs . He will exchange┬ádirectionless choice for ÔÇťpointless direction.ÔÇŁ This is no saccharine pop-philosophy conceit, though: Lewis-Kraus is a skeptically inquisitive narrator, with a sharp eye for the slapstick agonies and gonzo seekers of the Camino, and his wit and empathy keep him attuned to the ironies and epiphanies of the long walk. Modern pilgrimage, he writes, ÔÇťisnÔÇÖt about freedom from restraint but freedom via restraint.ÔÇŁ The pilgrim bug leads him to other routes around the globe, and the result is an often hilarious and ultimately moving perambulation toward an idea of what it means to be a travelerÔÇöand a personÔÇöin the modern age.

Hot Reads for Summer 2012: Power Brokers

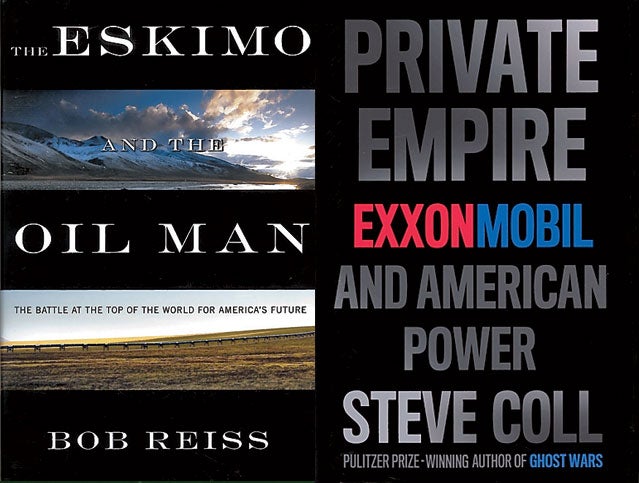

Two new books tackle the energy crisis from very different angles

WHEN SUMMER hits and gas prices shoot up along with the temperature and we all wonder why, books about oil become required reading. Steve CollÔÇÖs sprawling, Tolstoyan (Penguin Press, $36),┬ábegins with one oil spill, the , and ends with another one 21 years later, . In between, there is everything else: the fall of the Soviet Union, the long reign of Exxon CEO Lee ÔÇťIron AssÔÇŁ Raymond, the┬ácompanyÔÇÖs campaign against climate science, small wars in Indonesia and Nigeria, dodgy deals in Equatorial Guinea, Chad, and Russia, the invasion of Iraq, ExxonÔÇÖs use of SEC-defying accounting, its record profits, its billion-dollar political donations, its embrace of tar sands, its embrace of fracking, and, always, its unyielding┬ádedication to the ÔÇťExxon way.ÔÇŁ Its way, that is, or the highway. There is no reason a 600-page book about an oil company should be this gripping, but it is. Coll and his researchers interviewed more than 450 people; he traveled to Alaska, the Sahel, the Niger Delta, and the Middle East; the pace never relents. ÔÇťWe need to face some facts,ÔÇŁ says Lou Noto of Mobil, a company eventually swallowed by a hungry Exxon, in what will serve as Private EmpireÔÇÖs guiding passage. ÔÇťThe world has changed. The easy things are behind us. The easy oil, the easy cost savingsÔÇötheyÔÇÖre done.ÔÇŁ Everything here flows, or doesnÔÇÖt, from that.┬á

If Exxon once famously denied climate change, its rival has embraced it: since 2005, Shell has spent $3.5 billion in an attempt to tap northernmost AlaskaÔÇÖs melting Beaufort and Chukchi seas. This is the subject of ║┌┴¤│ď╣¤═° contributor Bob ReissÔÇÖs (Business Plus, $28), which focuses on the Inupiat mayor of the North Slope Borough and the Shell executive sent to win him over. The book is well timedÔÇödrilling may finally begin this summerÔÇöbut is quieter than CollÔÇÖs. Reiss shows the most outrage not over the collapsing Arctic environment, not over the resource curse that Coll describes so well. What heÔÇÖs angriest about, after watching ShellÔÇÖs man and the mayor reach a pro-exploration d├ętente, is governmental red tape. If drilling is inevitable in the Alaskan Arctic, we may as well streamline it. This makes his book one about process, while Private Empire is about power. In the end, Reiss writes, what makes America great is compromise. The story of ExxonÔÇöwhatever one thinks about the corporation itselfÔÇösuggests the opposite.

Hot Reads for Summer 2012: Young Men Vs. Wild

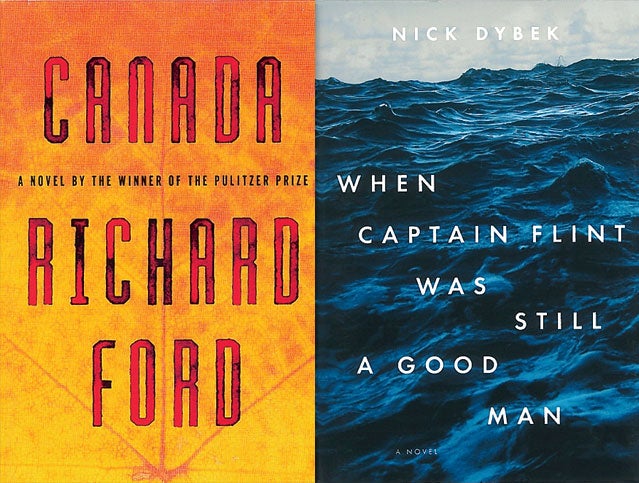

Green protagonists grapple with harsh landscapes in the summerÔÇÖs best fiction

The seasonÔÇÖs standout novelsÔÇöone from a rookie and the other from a┬áveteran man of lettersÔÇöconcern young males knocked loose to come of age in the northern wilds. Both are set in weathered, isolated places in the pre-Internet age, and the landscapes donÔÇÖt let the teenage protagonists mature without tragedy. Nick Dybek, son of noted novelist Stuart, debuts with (Riverhead, $27). ItÔÇÖs 1986, and 14-year-old Cal Bollings, too young to accompany his captain father to the Alaskan crab fisheries, stays home in the village of Loyalty Island, Washington, with his flighty mother. The local fisheries have been exhausted, and the crabbers are increasingly dependent upon bigger boats owned by one man, John Gaunt. When Gaunt dies and leaves the fleet to his only son, the townÔÇÖs livelihood is threatened. Cal is caught in a game of deadliest catch after he overhears the fishermen plotting the heirÔÇÖs disappearance at sea.┬áDybek can paint a salty landscapeÔÇöÔÇťLoyalty Island was the stink of herring, nickel paint, and kelp rottingÔÇŁÔÇöbut itÔÇÖs the fast whirlpool of lies, murder, and moral dilemma that drives the book.┬á

In (Ecco, $27), Pulitzer Prize winner Richard Ford ventures to the far north to deliver the finest book of his career. No special effects hereÔÇöbank robbery and murder are foretold on the first pageÔÇöjust overcast realism rendered in clean prose. ItÔÇÖs the early sixties in Great Falls, Montana, when Dell Parsons, 15, watches his father, a de-winged bombardier, run afoul of beef-rustling Cree Indians. Soon after, ParsonsÔÇÖs parents rob a North Dakota bank and are sent to prison. Dell is smuggled to Partreau, a ghost town on the Saskatchewan wheat veldt, and taken under the wing of Charley Quarters, a lipstick-wearing goose-hunting guide. Their employer is Arthur Remlinger, a hotel owner who caters booze and girls to the hunters and who poses as DellÔÇÖs surrogate uncle. The┬áaction comes to a head when two shady characters from RemlingerÔÇÖs past come for him and Dell has to choose sides. ÔÇťIf you say he should never have brought me there that night, that he changed if not the course of my life, then at least the nature of it ÔÇŽ if you say these things, you would be correct,ÔÇŁ Dell narrates. ÔÇťThings happen when people are not where they belong, and the world moves forward and back by that principle.ÔÇŁ Both novels culminate in murder, but DellÔÇÖs choice is far more devastating; FordÔÇÖs┬ánarrator, like the author himself, has the wisdom of a half-century of reflection.