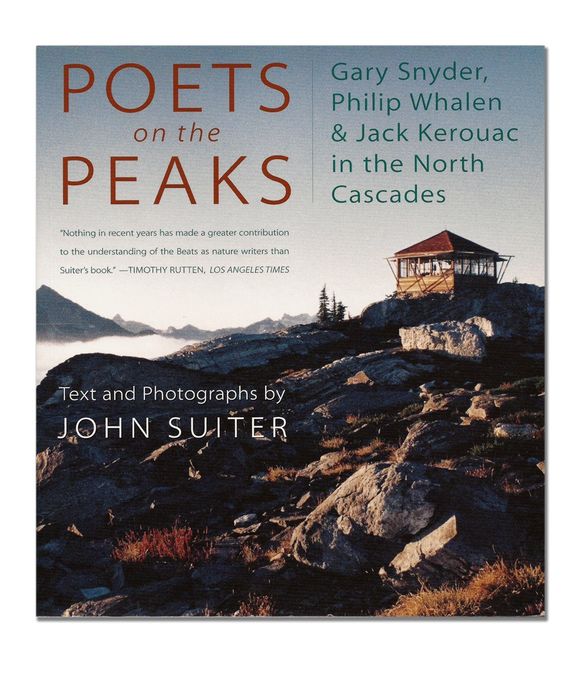

This review is the first for my list of the 34 best travel books you've never read, posted in no particular order. Up first, Poets on the Peaks, a travelogue that chronicles the varied routes the Beats took on their way to meeting in San Francisco in the 1950s.

#18 Poets on the Peaks

by John Suiter

Counterpoint (April 16, 2002)

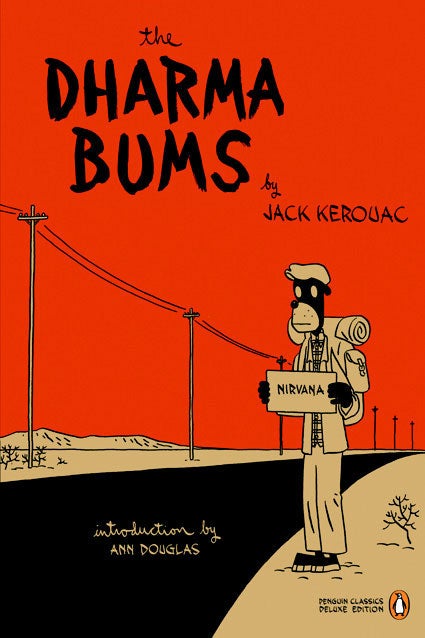

One of the greatest travel books published in recent times mirrors another, smaller book—that wasn't a travel narrative at all. It was a small novel published in 1958 that’s become a vade mecum for drifters, backpackers and train hoppers around the world. The first chapter of Jack Kerouac’s The Dharma Bums, in particular, plants the reader in the scene with such precise language and meditative rhythm, the experience is not so much of reading as it is watching scenery slide by—the taste of tobacco in your mouth, a half-finished bottle of Irish Rose in your pocket. Reading it aloud, I’ve been told, is the only way to truly get lost in the story:

Hopping a freight out of Los Angeles at high noon one day in late September 1955 I got on a gondola and lay down with my duffel bag under my head and my knees crossed and contemplated the clouds as we rolled north to Santa Barbara. It was a local and I intended to sleep on the beach at Santa Barbara that night and catch either another local to San Luis Obispo the next morning or the first class freight all the way to San Francisco at seven p.m. Somewhere near Camarillo where Charlie Parker’d been mad and relaxed back to normal health, a thin old little bum climbed into my gondola as we headed into a siding to give a train right of way and looked surprised to see me there. He established himself at the other end of the gondola and lay down, facing me, with his head on his own miserably small pack and said nothing. By and by they blew the highball whistle after the eastbound freight had smashed through on the main line and we pulled out as the air got colder and fog began to blow from the sea over the warm valleys of the coast.

The book continues in Santa Barbara, San Francisco, Berkeley, and at the famous��Six��Gallery reading where Ginsberg first read Howl and Gary Snyder, Philip Lamantia, Michael McClure and Philip Whalen performed. From there it follows Snyder and Kerouac up California’s Matterhorn Peak and through Kerouac’s musings of a rucksack revolution—as the two writers trade Zen wisdom on the summit, eat peanuts and raisins and prance back down the mountain high on enlightenment and starvation.

��

The novel is set in the years that followed On the Road. Character names are laughably disguised (Neal Cassady = Cody Pomeray; Allen Ginsberg = Alvah Goldbook; Gary Snyder = Japhy Ryder). In real life, the era marks the beginning of Kerouac's fascination with mountains and wilderness—as he follows Snyder and Whalen into Washington’s North Cascades and eventually becomes a fire lookout for the U.S. Forest Service.

It’s the latter adventure that John Suiter’s book, , chronicles. Beginning with a detailed history of the Skagit watershed in northwestern Washington, Suiter goes on to follow the poets’ individual paths to San Francisco in the fall of 1955, then up into the peaks the following year.

We caught up with John Suiter to ask him about his quest to research this book.

What's your background in mountain climbing, fire watching, other outdoor activities and nature in general?

I grew up in the suburbs of Philadelphia, about five miles west of the city. This was in the 50s, before the burbs were such a solid and dismal sprawl. Where I grew up was more like a small town, with lots of woods and open fields between us and the next little suburban town. There were still some farms around, riding stables and patches of woods, all disappearing fast.

It was East Coast, Middle Atlantic, the watershed of the Delaware River. As kids we played and hiked along the many creeks that flowed into the river. The creeks were badly polluted, although one of the thin little streams in my neighborhood had its source in a spring with a mossy limestone wall around it. It was the foundation of an abandoned springhouse, probably 150 years old or more. The water was crystal clear, straight from the rock, and we would fill our canteens from it before hiking off. So I got the basic notion early on that the earth was essentially pure, that it was people who fouled it.

We had no supervision or organization, certainly no schedules. “Where you kids going?” our parents would say. “Down the crick!” we’d say, and we’d be gone until dark, maybe hiking six or seven miles, never seeing an adult all day. We’d climb big sycamore trees, poke about the ruins of old gristmills, scramble around the glacial erradics. As teenagers we got high in those woods and had sex for the first time, on blankets, at the feet of great 200-year-old trees. So maybe that woods-and-creek landscape was charming and idyllic rather than powerfully sublime like the mountain west; nevertheless it was our “nature”—and for me always meant freedom, beauty and release from the ordinary.

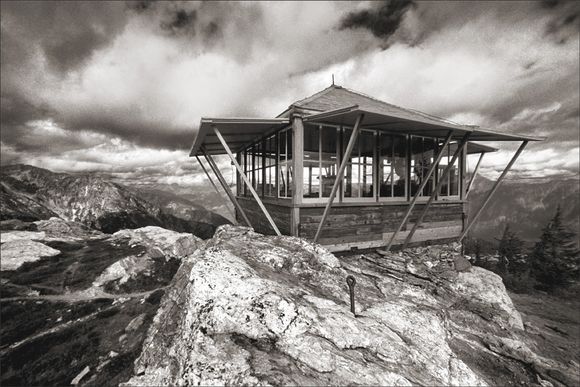

I have no background at all in mountain climbing, just hiking, really. The trails going up to the lookouts in��Poets on the Peaks��were all originally built for pack stock, so they may drive you nuts with switchbacks, but there is nothing technical involved in getting to the summits. The most difficult peak to access was Crater Mountain, where Snyder had his lookout in 1952. That’s an 8,100-foot peak, with some Class 3 exposure in one section near the top. There used to be some fixed ropes for the lookouts to use, but that was long ago. The eyebolts are still in the rock, but the ropes are long gone.��

As for fire watching, no background. I was a short-term lookout at Desolation and Sourdough mountains while working on the book, but I was there primarily as a photographer and a writer. Those lookouts are functioning fire lookouts, or they were when I was there anyway, but the Park Service put me there either very early or late in the season, when the fire danger was extremely low. Some of the more hard-core park service types were sort of bemused, I think, at this East Coast journalist coming out to do a photo-essay about Jack Kerouac. I did, however, take my few responsibilities seriously, recording the wind speed and temperature and humidity and so forth and calling them in on the radio. And I memorized the peaks and creeks in my radius to the point that on my last trip to Sourdough I did see one smoke and was able to nail its location just by eyeballing it, even before sighting it in the fire finder. It was across Ross Lake over in the drainage of Three Fools Creek, and I called it in, but my friend Maxine Franklin over on Desolation beat me to it. So it became “Maxine’s Fire.”

��

How and where did you learn such an exquisite, effortless writing style, or do you even know the answer to that?

If the writing reads effortlessly, that’s great; it means the artifice has been successful, because it sure wasn’t written effortlessly.��

Years ago I pinned up Kerouac’s “Belief & Technique for Modern Prose” over my typewriter, and I still find at least half of those axioms of his ring true for me on any given day—and the ones that don’t really grab me one year eventually will or have at some other time. When writing��Poets on the Peaks��one of his sayings that was like a mantra for me was “Dont think of words when you stop but to see picture better.”

I’ve always been in awe of Kerouac’s idea of spontaneous prose, the spontaneous flow. It worked for him.

In his journals, he would sometimes keep track of the numbers of words he wrote, piling up phenomenal counts, like Thomas Wolfe—10,000 or 12,000 words in a session sometimes. While writing��Poets on the Peaks��I was always hoping for something like that—that my diligence in staying at the keys and trying to “see the picture better” would be rewarded with an eventual flood from the collective unconscious into the form that I had sketched for my tale of poets on lookout.

Jack’s deluge of words never came, not to me. All I kept doing was one sentence after another, no flood. I was more like a bricklayer laying courses of brick, building up a wall brick by brick and course by course and raising the scaffolding a little higher each day.��

How do the mountains appear when you write about them (i.e. in your memory) compared to when you are in them?

When I was writing Poets on the Peaks, I was far from the mountains I was writing about, but they were always very close. In Boston, the view from my writing room window was directly into the back wall of the building next door to me. In terms of the view it was the polar opposite of the vast panoramas from the lookouts on Desolation and Sourdough. My writing room was almost the same size as a D-4 lookout—14 feet square. The lookout is practically like a greenhouse; you’re surrounded pretty much by glass and the 360-degree view outside encompassed more than 2 million acres; in my writing room the survey was no more than 200 square feet.

During the time of the book I made five trips to the North Cascades, usually for two or three weeks at a time. Then I would go from those huge spaces back to my block in the city, my apartment row, my inner chamber. The contrast was absolute. Some of my friends from Washington State sort of pitied me, I know; but the stark difference in setting worked in favor of the book, I’m certain, and as the saying goes, “A mountain always practices in every place.” My senses, compressed in Boston, were wide open when I got there. Of course, when I was back in New England, I also got up to the White Mountains as often as I could…

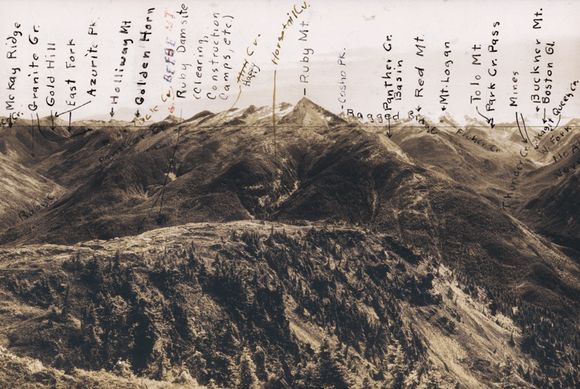

I would say, though, that during the writing of that book, my journalistic vision was as connective and far-reaching as it’s ever been. On one wall of my room I had taped together a number of quad maps covering the area that I could see when I’d been on lookout. I had my own photographs that I’d taken, and I had copies of old Forest Service “panoramics” with all the peaks and drainages labeled by hand, and I had pieces of chert and basalt and gneiss that I’d brought back from the summits. I had an eyebolt from the gully on Crater where there used to be ropes for the lookouts to get up through the scree.

I even had small pieces of wood siding from the original lookout on Crater, which had been burned by the Forest Service in 1968. Up on the summit there are still hundreds of small pieces scattered around. So I had all of these maps, and photos and talismans. And I had Gary’s journals that he kept, and some letters that he’d written from the lookouts; I had Kerouac’s Desolation journal and I had my own journal that I’d kept, wherein I’d detailed impressions of what I’d seen and felt. And I had no distractions. That little two-windowed room on Comm Ave in Boston was actually the perfect crucible from which to write about that vast mountain world on the other end of the continent.

How and where did you find so much information on the poets?

I was lucky, early on, to have extraordinary access to the Kerouac archive. This was before Kerouac’s papers went to the New York Public Library, when they were still in boxes at John Sampas’s house in Lowell. In 1994 I worked very closely with the Kerouac estate. I was the Associate Producer on��A Jack Kerouac CD-Romnibus, which was an amazing early multimedia project that first introduced the riches of Kerouac’s archives to the general public. In the course of that work I was able to read the original scroll version of��The Dharma Bums��and also Kerouac’s spiral notebook-journal that he kept when he was on Desolation Lookout. That Kerouac CD-Rom was far ahead of its time. It was like the first app; I hope Viking or someone brings that project into an up-to-date format—it’s a masterful hypertext edition of��The Dharma Bums.

As for the other main poets of��Poets on the Peaks—Gary Snyder and Philip Whalen…I was able to meet them in 1997, and interviewed them both a few times over the next couple of years. Their archives at Reed College and the University of California, Davis were my main sources of information, but there were other places—Columbia University, Bancroft Library at UC Berkeley, San Francisco State’s library…all the special collections libraries I cite in the back of the book.

One of the “peaks” in��Poets on the Peaks��is not a mountain, but the peak moment of the Six Gallery reading in San Francisco in 1955. My reconstruction of that event is one of the things I’m most satisfied with in the book, and the “information” came from my good fortune in being able to hang out with four of the five poets from that night—individually with them, almost 50 years after the fact and do interviews and hear their retellings of the evening, all in one condensed week-long period in December 2000. I sat down with Gary Snyder, Philip Whalen, and Michael McClure, and Philip Lamantia. Ginsberg had been dead for a few years, but I had been to half a dozen Ginsberg readings over the years, going back to 1966 or so, and felt that I'd be able to write about his performance based on what I had seen of him. I had never had a chance to meet Kenneth Rexroth, the emcee for the gallery reading…but each one of the living poets had his own very vivid imitation of Rexroth, his words and gestures, each one channeled some aspect of Rexroth. It was something to hear his voice coming through these other guys, and it was an extraordinary supersaturated experience to have those personal retellings one day after another in the Bay Area back then. Each man was so into it, so intense about his own reading, to get it right, and so generous and comradely regarding his fellow poets’ roles… ����

What are your favorite travel books?

It depends what kind of travel, of course. I just read a really good book on writers in Paris by David Burke, published by Counterpoint Press, my publisher. He goes way beyond the “Midnight in Paris” level and covers all of Paris, and is really strong on the 19th century writers. He's very detailed, giving exact addresses, and in some cases, exact room numbers where certain writers lived—like the room where Baudelaire wrote Fleurs du Mal.�� Bill Morgan’s Beat Generation walking guides to San Francisco and New York are very good, and now he has one for all of America.��

I don’t really read “travel books,” but I do use books—poetry, novels, biographies, histories, natural histories—as guides to places that I visit, very much so. I just moved to Chicago last fall, and I’m getting to know my neighborhood in part through some of autobiographical writings of Kenneth Rexroth. Rexroth wrote in vivid detail about the radical and “hobo-hemian” life of Chicago’s Near North Side in the 1920s. It’s almost like reading archeology, the area is so different now, but I use his writings as a walking guide sometimes. It’s appalling that he is not even mentioned in any considerations of Chicago literary history—it’s a major oversight.

A travel writer can be anyone who writes deeply about place. My friend Tim McNulty, who lives out on the Olympic Peninsula, is not a travel writer per se, he’s primarily a natural history writer, but he knows so much about the Olympics and his descriptions of the trails and wildlife are so accurate and passionately written that I would urge anyone headed that way to pick up a copy of his recently revised Olympic National Park history. For trails and high routes in the North Cascades, Fred Becky is still the man, as long as there is ice up there. And I know that people use Poets on the Peaks for the Upper Skagit. There are copies in the lookouts.

Bill Porter, a.k.a. Red Pine, the Chinese translator, is a great pilgrimage writer. He leads guided tours to Taoist and Buddhist sites in China. And Douglas Brinkley’s recent book on Alaska—The Quiet World, although primarily history, is fascinating reading for anyone traveling there. These are all, I realize, idiosyncratic choices…��