When Malinda Chouinard parked a trailer in front of climbing-gear company in Ventura, California, in 1983, she had no idea it would eventually become a model for on-site corporate childcare. She just wanted to help her friend and colleague, Jennifer Ridgeway, who was breastfeeding a colicky newborn.

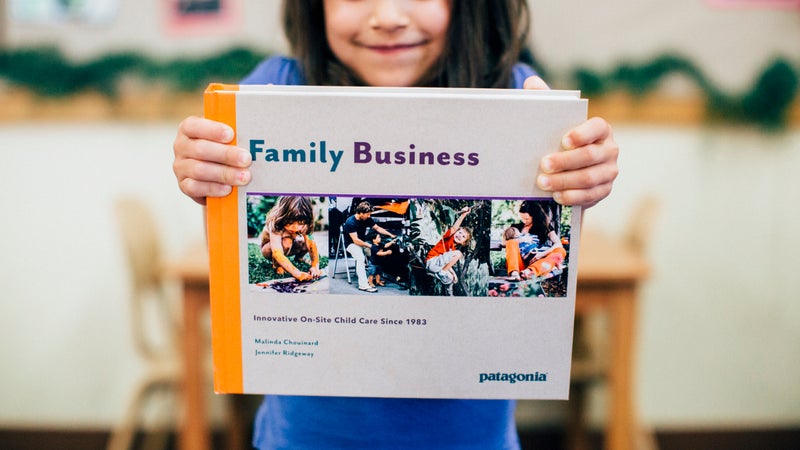

A former early childhood teacher who, along with her husband, , eventually grew Great Pacific Iron Works into the global outdoor retailer Patagonia, Malinda had brought her own baby into the offices a decade earlier. “I had worked on my own for years,” she writes in , the book she and Ridgeway co-authored for Patagonia in 2016, “but nothing prepared me for the isolation and exhaustion of being a working mother.”

The following year, Malinda replaced the trailer with a room in the back of the company’s newly expanded building, complete with child-size sinks and toilets. “I began to make unilateral decisions for which I had no budget, no authority, and zero preparation,” she writes. Kids and babysitters ran wild in there for a couple years—“It was like something out of ,” recalls Ridgeway—until 1985, when the company hired a full-time teacher and staff. With that, the (GPCDC) was born.

The idea was nothing short of revolutionary—then and now. In two-thirds of married-couple families, both parents work—but only 13 percent of U.S. employees receive paid family leave, according to Family Business. In the , more often than not it’s still the women who leave the workforce. From the beginning, Patagonia has tried to stem the exodus of mothers by providing 16 weeks of paid maternity leave, as well as 12 weeks of paternity leave. “Recently someone at the company was trying to remember when we started offering paternity leave,” says Dean Carter, vice president of human resources at Patagonia. “No one knew. We’ve always given it. Just from the very start, it’s been part of our culture.”

Today, the GPCDC serves 80 kids, from birth to age nine, at Patagonia’s headquarters in Ventura. Last year, the distribution warehouse in Reno, Nevada, opened an infant room and will begin enrolling toddlers in March. The Ventura site offers an after-school program and a summer surfing camp and provides a company bus to pick up enrollees. The company even pays for a childcare professional to travel with parents of nursing newborns when their work takes them on the road. Carter estimates that 85 percent of Patagonia employees with kids enroll theirs in the program, paying a sliding-scale fee that ranges from $500 to $1,300 (with assistance available to qualifying families).

On its own, the organic evolution of Malinda Chouinard’s vision would make a good story. But when you add in the financial ingenuity, you begin to wonder why so few companies have followed Patagonia’s lead. The company conservatively estimates that it recoups 91 percent of the annual $1 million childcare budget through federal tax credits, employee retention, and productivity. Other intangible benefits of on-site childcare include improved morale, higher loyalty, and a greater number of women in upper-level leadership positions, which, as Malinda writes, “makes business smarter and more creative and improves performance.” At Patagonia, women make up 50 percent of the workforce, including about half of upper-management positions. According to Family Business, 20 to 35 percent of , while a staggering 100 percent of Patagonia mothers return to work.

At Patagonia, the short commute between design offices, retail space, and the childcare center allows mothers to nurse on demand or , the way Malinda did when her children were young. Dads can stop by the garden for lunch or to put their children down for a nap. The result is a corporate culture that completely redefines work-life balance. “The idea of work-life balance is ridiculous, like it’s a seesaw that goes back and forth,” says Carter. “People are still hanging onto this idea that we shouldn’t bring life into work, but the iPhone changed all that. Work is with you constantly, and life is going to be with you constantly. Very soon, more and more people are going to demand that life and work are integrated.”

What’s more, the childcare center sounds downright fun. Babies and children spend at least half their day outside, napping and playing in the outdoor classroom. There’s a climbing wall and a garden and a playground with plenty of loose parts to encourage problem solving and interactive learning.

It’s little wonder that since the book’s publication, visits to Patagonia’s employment page have jumped 300 percent, according to Carter. These are perks with serious long-term benefits. (Just ask the second- and third-generation Patagonia families: 18 employees grew up in the childcare center, and four children are currently enrolled whose parents went through the program). Patagonia also fields dozens of calls each month from companies interested in creating their own on-site childcare centers and freely shares starter kits that include sample budgets, job descriptions, and employee surveys to help determine childcare needs.

It’s not as daunting as it might seem. “When Patagonia started childcare 30 years ago, it was a very small company with 50 to 70 employees,” says Carter. “I tell companies now to start with an infant room. Infants don’t take up a lot of space, but infant rooms have the biggest impact. They offer a little bit of breathing space for a new mom who’s just had a baby, is sleep deprived, and is coming back to work and needs to find childcare she can trust. You can start small. It’s not that difficult.”

Patagonia certainly makes it look easy. For 34 years, the company has been making gear and, behind the scenes, building families and raising kids to be curious, connected, and creative changemakers. There’s even discussion of expanding the childcare center into an outdoor experiential school, modeled on for older kids. “We’re a village,” says Carter. “These aren’t widgets working for us. These are parents with kids depending on us to come home for dinner. What we’re doing isn’t something that ends at 5 p.m.’