I’m standing on the deck of a ship somewhere in the vast Norwegian Arctic. Although it’s 3 a.m., the sky is incandescent, a muted gold. It is the last night of our seven-day voyage in the remote archipelago of Svalbard, and my friends Patty, Nina, and I have vowed to stay up so we can experience the surreal magic of an Arctic summer night. Twenty-four hours of light. We laugh, sip glasses of champagne. The air temperature is 36 degrees, but I’m wearing a long-sleeve shirt, tennis shoes, and jeans. No down jacket, furry hat, or thick gloves. I want to feel everything. As I look out to sea, icebergs the size of tanker trucks glide past.

Two years ago, I could not have imagined feeling this happy. After a brief and brutal illness, my youngest brother had died. I was moored in grief. A year apart, we had explored the natural world together from the time we could walk. If not for Jim and his love of the ocean and our childhood stomping grounds of San Diego, a paradise with miles of beach and perpetual surf, I might not have become so wild and free. I might not have dared to be who I was—an athletic, independent girl. I was the youngest of four children, the only female, and in the 1960s, girls were not exactly encouraged to explore the world. We could roam only so far before being yanked back, constrained.

I remember being furious at a young age, perhaps seven or eight, because I could not play baseball like my three brothers. The same when I was 12 and wanted to surf. My brothers were typical Southern California surfers, brown and broad-shouldered with hair kissed by the sun. Our house was littered with sand and damp beach towels. The smell of resin permeated the air. I often went with Jim and his friends to Ocean Beach, a grubby hippie enclave. But when Jim and his friends paddled out past the break, I did not join them. I had been taught that girls did not surf. We were supposed to lie on the sand in our bikinis, work on our tans. Merely watch.

This exclusion infuriated me. I had been swimming in the ocean since I was four and felt as comfortable in the churning waves as I did on land. I had swum out of rip tides that threatened to pull me far out into the Pacific. I was a passionate body surfer and could catch six-foot waves and ride them easily into shore. It is no mystery why, years later, I would write a story about the explosion of California surfer girls in Carlsbad. I wanted to be one.

Jim understood my need for adventure better than anyone. My mother, because she was terribly sick after doctors removed a tumor from her brain, could not advocate for me. My father, a doctor, was mostly absent because of long work hours, but also because he had fallen in love with a nurse in his office. When he was home, he and my mother fought. Lonely and neglected, Jim and I reached out to each other. We found joy outside.

I did not know the word “wanderlust,” but even then I had a severe a case of it. I followed Jim nearly everywhere he went—down steep canyon slopes on pieces of cardboard on our bellies, over tall fences and up fragrant pepper trees, off high diving boards into the deep end of swimming pools. And he happily obliged. “Come on,” he’d say, plunging into the waves, where stingrays, jellies, and other sea creatures lurked. “Come on,” he’d say, handing me his skateboard, so I could understand the thrill of barreling down our street on a narrow slab of wood.

I had been taught that girls did not surf. We were supposed to lie on the sand in our bikinis, work on our tans. Merely watch.

Those early experiences taught me to take risks. Because I desperately wanted to travel, they gave me the confidence to explore. When I was 19, I left San Diego for good to attend college at Berkeley. I traveled whenever I could. When I was 20, I took the train from Berkeley to Mexico City with some friends, standing happily in the sweltering third-class car because I thought it would be exciting to be in the lively Mexican capital during Christmas. (I was not disappointed.)

A few years later, I drove up the Alcan Highway in a battered pickup truck with my college boyfriend through Canada and Alaska. Camping in the Alaskan wilderness, I saw a gaggle of moose and my first grizzly bear and not a single person for four days. By the time I was 28, I was working as a writer, a job that took me first to the countryside in Nicaragua and then to a newspaper job in Los Angeles, where I have lived ever since.

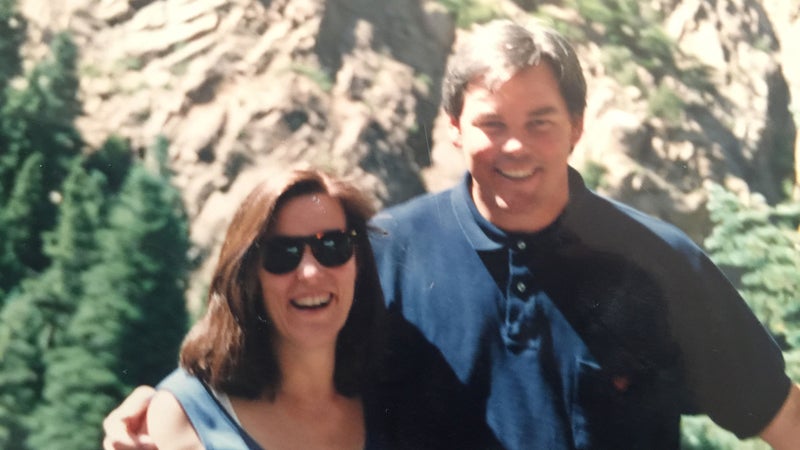

Jim moved around, too, eventually settling in Colorado Springs. Despite the distance, we stayed in frequent touch. We called each other often, wrote letters, visited when we could. We got married within a year of each other, attended each other’s weddings. Then, because our children were the same age, we continued to have adventures. During winter breaks, we piled into a condo in Breckenridge and skied in the glorious Rockies. Despite my wish to be so, I wasn’t exactly fearless—I had learned the consequences of being an adult. But I loved floating down the mountain in the bright alpine sky, making my way through the pine trees to the lodge. I loved watching our kids, two boys and two girls, fly down the slopes on their tiny skis, and later on their snowboards. They were fearless. Most of all, I loved watching Jim, a gifted athlete. He bombed down the steepest runs and the biggest, iciest moguls, snow spraying out behind him. The mountains were his element, his canvas, just as the ocean had once been.

And then he got sick.

In November 2010, I got a call from one of my brothers. Jim had been rushed to the hospital in Colorado Springs in excruciating pain. During an emergency surgery, doctors discovered he had advanced colon cancer. Although they removed much of the tumor, Jim’s prognosis was grim. He might have two months, a month, to live. He was 58. I got on a plane and flew to Colorado.

Jim was a good-looking guy. Six-foot-two, with chestnut hair, hazel eyes, and a killer grin. But when I first saw him in that hospital bed, he resembled a shadow of himself. My heart shattered, and I struggled not to cry. He grinned. “Hi, hon,” I said, taking his bone-thin hand in mine.

Soon came another shock: Jim also had tested positive for Huntington’s disease, a rare and fatal genetic brain disorder. Because of the sensitivity of Jim’s diagnosis, at first only a few people knew. Jim never knew. He was already suffering enough. What good would it do to tell him?

As his condition worsened, Jim begged to be freed from the hospital. One night, as I was leaving his room, he asked, “Can I stay with you at your hotel?” He was in a wheelchair then. “You can’t, sweetie,” I said.

After he was released that November, I flew back and forth to his home in Colorado Springs, watching him sleep, offering him food he could not eat, putting my headphones to his ears so he could listen to the Beatles on my iPod.

After I hung up, I sat on the sofa in the family room beside my teenage daughter and wept. But for all my sadness at losing Jim, I was also grateful: he was no longer suffering.

I was determined to be cheerful. As Jim sat propped in bed against a wall of pillows, I reminisced about our childhood, our crazy adolescence. I remembered the long hours we played kickball and hide-and-seek, poked around in the tide pools at Ocean Beach, how we’d stayed outdoors on our bikes until the last sliver of light was gone. I remembered the awful cheap wine we drank, the dope we smoked, listening to the Doors and Led Zeppelin on his record player, the hours we spent cruising Sunset Cliffs. “Remember how my friends thought you were the cutest guy in school?” I said. He grinned and then fell back asleep.

As the days passed, though, I could feel myself coming apart. It was snowing in Colorado. I shivered constantly, despite wrapping myself in layers of down and wool. In an effort to blunt my pain, I began drinking a lot and didn’t especially care. Late one night, after a sad and chaotic afternoon talking with the hospice workers, I returned to my hotel. I called my husband, sobbing so frightfully that a man knocked on my door to ask if I was OK. I realize now that this was the beginning of something hard and unyielding: grief.

Jim died on Christmas Eve 2010. I was standing in my living room in California, lighting candles on the evergreen-draped mantle, when the phone rang. My breath caught. I knew he was gone. I had been expecting the news for days. After I hung up, I sat on the sofa in the family room beside my teenage daughter and wept. But for all my sadness at losing Jim, I was also grateful: he was no longer suffering.

In the coming months, I was paralyzed by grief. I missed him terribly. With our similar looks and our childhood bond, I had always felt like Jim was like my twin. I missed his sense of humor. I missed our arguments about politics. I missed hearing his voice. I would pick up the phone to call him, only to realize that I couldn’t. Months passed.

When I was depressed, I usually found comfort in nature. Even before Jim got sick, I ran regularly at the Rose Bowl, beneath the dark San Gabriel Mountains and billowy white clouds. Or I trekked along the dirt trail in the arroyo, under the shady eucalyptus and sturdy California oaks. Sometimes, when I was restless, I’d even drive to the ocean. Nature is where I could breathe, find calm. But for months I’d stopped doing even that. Most days I didn’t want to leave the house.

After nearly a year and a half, I knew I had to do something. I was tired of being unhappy. I was having trouble writing. Out of desperation, I decided to take a writing workshop. While I’m not much for groups, I thought it might help nudge me out of my despair.

The workshop was held in a bungalow in breezy Marina del Rey, which, considering my inability to leave the house, was exotic enough. Like me, the other people were longtime writers, looking for, as one person so eloquently put it, “a kick in the ass.”

As we sat around a long table, sipping coffee and nibbling on bagels, we did a series of creative writing exercises. One of them was jotting down work aspirations we secretly held. Ones that were out of the box, grand. The idea was that by writing them down, and then saying them aloud to the group, we could make these aspirations real, will them into coming true. I was skeptical.

In my usual self-denying way, I listed the stories I thought I should be doing, the book I thought I should be writing. At the bottom, I impulsively scribbled a long-held wish. Go on a . I thought nothing more of it.

A few weeks later, I was scrolling through my email when I saw one from David, the workshop leader. The subject line said something like “Want to go to the Arctic?” When I opened it, David’s email said he’d been invited to go on a voyage to the Norwegian Arctic with several National Geographic photographers, but he wasn’t able to go. Did I want his spot?

As the ship moved through the black Barents Sea, the power of nature again seeped into my skin. I loved the isolation, the feeling of being removed from everyone and everything I knew.

I think I might have screamed. Just to be sure, I read the email again. A month later, in June, I flew to Oslo, the Norwegian capital. I spent the afternoon wandering the waterfront, where Vikings once harbored their wooden ships, and the city’s vertiginous opera house. In the strong Atlantic air, thousands of miles from home, I began to feel like myself.

But it was in the Arctic, in a mesmerizing wilderness of teal-colored icebergs and giant walruses and regal ice bears, where I truly came back to life. The second day, I pulled on my Muck boots and climbed into a Zodiac, going ashore for the first time. I was thrilled to be on the tundra, and we trudged up a rocky slope overlooking a ring of glaciers. On the way, I saw my first wildlife: a scraggly Arctic fox, six tawny reindeer, a bevy of orange-beaked puffins snuggled in the cliffs.

As the ship moved through the black Barents Sea, I came to love the isolation, the feeling of being removed from everyone and everything I knew. I loved standing at the railing on the bow, hearing the ice below me crack, the engine groan. Except for the piercing cries of black and white gulls called kittiwakes, the Arctic was almost silent. The stillness seemed to calm me, too. Bundled in a fur hat, down parka, layers of fleece, and snow pants, I’d stay outside until I was shaking. Then I’d duck inside the map room, where there was coffee and hot chocolate.

Standing on that deck, I saw polar bears in the wild, a dream I’d had since I was a girl. One bear was roaming from one ice patch to the next in open water, only 40 or so yards from the ship. He was massive and beautiful. He had just killed a seal, and its carcass lay in a pool of crimson blood on the white snow. At one point, the bear stood up, turned his head in our direction and sniffed the air. He watched us intently, swaying on his big wide feet. He was so close that I could see the black skin peeking through his thick white fur.

I spent hours shadowing a National Geographic photographer, who taught me the intricacies of shooting in an all-white landscape. I probably took thousands of photos: walruses plopped on slabs of ice, polar bears buried in snow, birds nesting on soaring cliffs. Skyscrapers of ice. I wrote every day.

One afternoon, I stood at the railing on the bow. No one was around. I looked out at the sky, the thick plates of ice shaped like a jigsaw puzzle, the dark Barents Sea. I stood there for a long time, the wind stinging my cheeks, overcome with wonder. I thought of Jim, but I no longer felt unmoored. I thought of how much I loved the Arctic, and how much he would have loved it, too.