“Mom, would you love me if I was black?” my six-year-old son, Skyler, asked as he climbed into our claptrap, used Suzuki jeep. We were sitting in the red clay parking lot of (AISM), in the capital city of Maputo.

“Of course, I would. Why?” I answered, turning the key in the ignition.

“I dunno. I was just thinking.”

I wondered if the question was connected to his observation that Tunji, a black West African boy in his first-grade class, was the fastest runner. Skyler had always been a fan of fast. Whether by land, sea, or air, maximum speed had been the necessary characteristic of each of his favorite animals. So if being black meant speed, it couldn’t hurt to ask.

A few months into our year living in Maputo, Skyler was beginning to tackle the big questions, like skin color. What did it signify? Mozambique is 99 percent black and ruled by a small black elite. The few whites there—our family being one—were another privileged class.

Some weeks later, we were playing in the tiny yard of our house in one of Maputo’s upper-class neighborhoods. Running on the crab grass by hibiscus bushes, around lemon and banana trees, Skyler kicked the soccer ball into the wall surrounding our house. Jaime, our day-shift guard, caught the ball and tossed it into Skyler’s running feet.

“Toca a bola!” Jaime shouted, his huge smile wide in his black face. “Pass the ball!”

When we walked back into the house leaving Jaime to his station by the front gate, Skyler asked, “Why are all the poor people black and all the rich people white?”

“Well, they’re not always,” I responded. “There’re plenty of whites who are poor and blacks who are rich. The guy who owns this house is black.” But I knew I was stalling, buying time to figure out how to answer this complicated, weighty, controversial question that had just come out of the mouth of a six-year-old.

“Sometimes I just wish I were black,” our ten-year-old daughter Molly said another day, as we picked our way through the rubble of Maputo’s sidewalks. “Then people wouldn’t always be asking me for money.” She, too, was trying to sort out the economics and race equation.

We were headed to a fabric store in Maputo’s elegant but crumbling colonial downtown. There we would sift through embroidered silks from India, dotted Swiss from England, and batiks from Holland in search of fabric to be delivered to the seamstress whom we’d commissioned to make us summer dresses for a few dollars apiece.

The big questions are difficult for anyone to answer, and travel to the third world puts them right in your face—just where we wanted them for our kids.

When I had the opportunity to apply for a second sabbatical from the University of Montana, we decided to look for a place that met our criteria for raising globally comfortable, globally tolerant, globally aware children.

The criteria were:

- A place where English was not the primary language

- A place where white was not the primary race

- A place where people were less affluent

Well, that left most of the world.

Our theory was if we wanted our kids to feel at home in that world, they would need to understand that people do not always speak English, but that one can still communicate. They would need to feel comfortable being in the racial minority, in part so they could empathize with those in the minority at home. And it would be good for them to see how much less, materially, most people in the world have.

Molly was at the incipient mall-rat stage. “I need to have…” was becoming her standard opening salvo. Every time I heard that line, I remembered the ingenuity of the Tibetan nomads in Qinghai, China. They gleaned everything they needed from a yak: wool for tents, dung for fires, milk for yogurt, meat for their bellies. But their needs weren’t great. How much do we really “need”?

Determined to find a place that would meet our criteria, Peter and I took the and set off for our favorite Missoula oyster bar. We slid onto stools at the counter. Then we practically threw the dice.

“What about Mozambique?” Peter had just been to Mozambique for an ���ϳԹ��� magazine assignment. “There’s a crashing third world economy, just what we need.” He smiled.

Skyler attended first grade and Molly fifth at the American international school in Maputo. There was nothing very American about it. The teachers were British, Indian, and Mozambican. The students came from all over the world—mostly Europe and Africa—and many spoke not one or two, but three or four languages.

“Mom, why do I just speak English?” Skyler came home asking. “Mikas [his Lithuanian/Danish friend] speaks four languages.”

“Mom, why are the poor people so much happier than the rich people?” Molly asked another day as we were driving to the market, bumping through the rutted dirt roads of a mud-hut slum.

I could see why she thought this. Pairs of girls stood inside elastic loops stretching them long so a third could jump through the strands, like a life-sized cats cradle. Guys hung out in front of dark doorways singing along to boom boxes. Women washed laundry in plastic tubs, shouting out to passersby. It was all out there, in the open—the laughter, the teasing, the flirtation—life lived out loud.

In our elite neighborhood, the upper class hid behind walls. Windows were barred, no sounds escaped. In the weeks after we moved in, when we were without a car and walking, we met the houses’ guards. They played checkers with bottle caps on boards drawn with chalk on sidewalks. After a year, we had yet to meet one of their employers, the inhabitants of the houses themselves, our neighbors.

When we got home to the States, Molly’s tune had changed. “I know I don’t really need this, but if it would be okay, I’d really like this shirt.” For Skyler’s next birthday, he asked his friends to donate clothes we could send to the kids of Jaime and Armando, our two Maputo guards.

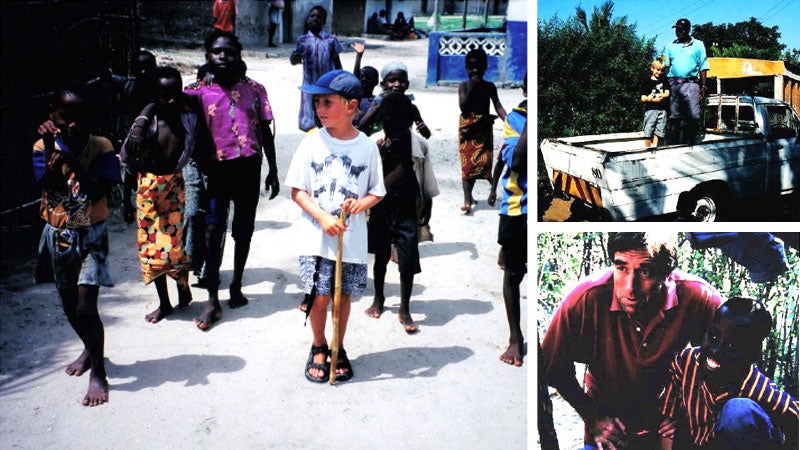

Simone, Jaime’s 12-year-old son, had occasionally come to work with his dad. Skyler always wondered at Simone being so small at 12, the same size vitamin-fed Skyler was at six. When we left, Skyler wanted to give Simone his game of Guess Who. We took it, along with the furniture we were giving, in a pickup to Jaime’s house with its hedge rather than a wall, its three rooms rather than our three stories. While Jaime moved the furniture in, Peter, Skyler and Simone sat in the dirt outside, Peter coaching Simone as Skyler explained the game’s rules, the board between them.

It was for this that we had come. This curiosity about people unlike ourselves. This empathy for those with less. This chance to make a connection. This is why it’s worth living abroad.