For the past month, I’ve been thick of old anxiety. It starts in my ear, with that shrill, now-familiar ringing and seeps into every cell: brain, fingers, toes, feet, elbows. Being in it feels like swimming against a riptide or wrestling a boa constrictor. If I stop fighting, I’ll be swallowed whole, but struggling—like swimming against the riptide—only carries me farther out to sea. So I tread water, looking for an opening. What will save me this time? Acupuncture, camping, running, meditation, sitting on a plane out of Phoenix with my four-year-old’s head on my lap and the blackest of deserts far below?

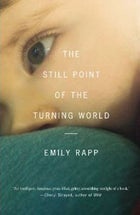

The Still Point of the Turning World.

The Still Point of the Turning World.��

Life is so beautiful, it’s terrifying.

Early this morning, here in Santa Fe, Emily Rapp’s son, Ronan, died of Tay-Sachs disease. Emily has been writing about Ronan’s journey with this rare and fatal degenerative disorder since he was diagnosed two years ago: on her blog, on Facebook, and in “Notes From a Dragon Mom,” . Her memoir about mothering Ronan, , will be published next month.

I first started following Emily’s story in late 2010, after our mutual writer friend, Rob, introduced us on Facebook. She taught creative writing and had a new baby and loved to hike, he told me. We should get together with our kids, he said. We should be friends.

But my father was dying, and I was preoccupied with grieving and traveling—specifically, grieving and traveling with my five-month-old daughter in tow. By the time I got around to following up on Rob’s introduction, it was January. My father had died, and Emily’s Facebook page had a worrisome tone. I scanned back a few days, weeks and then forward, trying to make sense of what I was reading. There were mentions of doctor appointments and missed milestones, encouraging comments from concerned friends. Then, in plain black type, came the diagnosis: Tay-Sachs. Shocking that something so shattering could be laid bare on the screen, seemingly innocuous and unadorned.

I sat at my computer on that Saturday morning, as the world outside frosted over, feeling stunned. I didn’t know Emily. I didn’t know her son, Ronan, but I knew this terrible, final, irrevocable thing about her. I felt as though I ought to know her better, now that I held this terrible news, even while I knew with unequivocal certainty that we would not go hiking or go out for tea afterwards and talk about our favorite writers or new books we loved. Our friendship was over before it began. But what I didn’t know is that I would think of Emily nearly every single day since then, and marvel at her strength and bravery as a mother and weep for her dark-haired one-year-old son who might not live to be three.

But many days when I thought of her, it was with despair and fear for my own children, for their fragility and mine. How is it possible to keep them safe, to keep us all safe? Last fall when my father was dying, I saw for the first time how life hangs in a delicate balance, a spider web of hope, good health, and possibility strung from the ceiling, tenuous and easily swept away. Every irrational fear that could worm its way into my brain did, lodged there like an unwelcome, intractable houseguest. I spent many months in a deep state of anxiety. I had known, of course, that everyone eventually dies. But I hadn’t really known it. And now that I did, I couldn’t stop thinking about it, worrying about it, dreading it. Emily’s story haunted me, a devastating reminder that it happens to anyone, everyone, all the time: to fathers who are not so very old and children who are far too young and to mothers who love them madly.

All winter and spring, I read her , and watched as she grappled with Ronan’s illness and her own unscripted role as a mother of, as she wrote, “a child with no future.” Her writing was full of love, unflinching. Reading her stories, I could tell that the act of writing was essential to her, a way to save her own life even if she couldn’t save Ronan’s. There was nothing extraneous—every deliberate word seemed to propel her forward into a new uncertain world, her world, like hands fumbling for a light switch in a darkened room. One step, and then another—words on the page a lifeline from this moment to the next. I felt this, viscerally, absolutely, and was filled with awe.

And guilt. How could I write about running or eating peaches or teaching my four-year-old to ski or my one-year-old to sit still in a raft like a seasoned river baby, when another mother, whose baby will never grow to ride a bike, was wrestling with the biggest question of all: How do I help my child live and die with grace and dignity? If I really thought about it, it seemed possible, and perhaps preferable, to stop writing altogether.

But I didn’t. Emily inspired me. I kept muddling through, even when the hollowness of my own stories, the seeming irrelevance of them, felt like a deliberate slap in the face to this mother whom I didn’t know but who had been generous and open enough to let me feel as though I did.

Like most writers, I write to make sense of the world, and my own life. Sometimes when I’m very lucky, the world and my little slice of it overlap in serendipitous ways, and I remember again how important it is to always keep my heart and eyes open, that inspiration comes from remarkable places, and that everything leads us to a new place. When this happens, it feels as though we are pieces in a larger puzzle that is slowly forming, fitting itself together, revealing itself gradually, in increments, until we can see a new picture in its entirety. This is how it has felt reading Emily: heart-wrenching, tragic, humbling, inspiring.

On this day, I see my fear and anxiety in a new light, with more patience, acceptance, and compassion. “Parenting, I’ve come to understand, is about loving my child today,” Emily wrote in The New York Times. “Now. In fact, for any parent, anywhere, that’s all there is.” These words are a gift, and consolation, to us all, but at such an unbearable cost.

Ronan died at 3:30 this morning, surrounded by family and friends. It was the blackest of nights, but there was light all around—Ronan’s and Emily’s and everyone who knew him and loved him or didn’t know him and loved him still. Death is life, I realized today, as I ran up a mountain trail and stood at the top, facing south, to where Ronan and Emily were. Even at the end, there is so much fullness, so much light. It’s unending.

So I will keep skiing with Pippa. I will teach Maisy to swim. I will take them camping and stroke their blonde hair when they fall asleep in my arms on an airplane after an eternity of whining for a new Dora coloring book. And I will keep writing, about raising my daughters to be fiercely alive, outdoors, in the wind and the sun, crashing their bikes and getting back on again. This is OK. This is more than OK. This is my way out. This is what I do today. This is how I live now. This is all there is.