“Like my cat?” our three-year-old, Molly, asked the pre-school kids around her, holding up her drawing (a cryptic jumble of lines).

Molly Stark-Ragsdale in her festival dress.

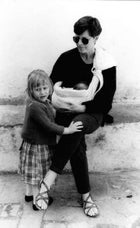

Molly Stark-Ragsdale in her festival dress. Amy with Molly and Skyler in the “hammock sling thing.”

Amy with Molly and Skyler in the “hammock sling thing.” Graduation from Arco Iris preschool.

Graduation from Arco Iris preschool.They looked at her blankly.

“Do you like my cat?” she repeated, louder.

Still the blank looks.

“DO YOU LIKE MY CAT?” she yelled.

They started to look dismayed, puzzled.

You always hear kids are sponges for language, but at three Molly just didn’t get the conceptÔÇöthat there are more than oneÔÇöand that getting louder and louder in English when everyone around you speaks Spanish, won’t get you anywhere. You have to match the key to the door or you can’t get in, at least not all the way. But gradually, unconsciously, it dawned on her, and she gained an understanding of language she’d have for life.

We’d enrolled Molly in┬áArco Iris, a preschool down the street from our rented rooftop apartment in the┬áthe ancient-Phoenician, walled town of Cadiz in Andalusia in southern Spain. I was on┬ásabbatical from the , and our second child,┬á Skyler, was just five weeks old. We’d chosen Cadiz for its historic charmÔÇöits valentine-heart-colored houses, eighteenth-century stone cathedral, overflowing fish and flower markets set on a blustery spit jutting into the AtlanticÔÇöand because it wasn’t too expensive and had no major diseases.

At noon each day, my husband, Peter, would pick Molly up from school and they’d cross the street to a neighborhood bar for lunch. Molly would order her favorite, tomato stew with snails, and Peter would knock back a shot of sherryÔÇöa popular local pick-me-up from Jerez, just across the bay.

In the meantime, I carted tiny Skyler, tucked into a sling, down the cobblestone street to the community center, where I’d rented a second-floor studio to choreograph. On the way, I’d stop at the flower market. I’d rest for a moment at an outdoor table amid buckets of gladiolas and roses and shore myself up with a demitasse of dense coffee. Inevitably, stern old women would tell me my baby was going to have a deformed back if I kept carrying him around in that hammock-sling thing, and to take my germ-infested pinky finger out of his mouth.

“Use a pacifier if he cries,” they’d say in Spanish I barely understood, but their disapproval was unmistakable.

I had squeezed in only a couple months of Spanish tutoring before we left, thinking I was pretty good at languages and that I’d pick up more when we arrived. I was wrong. It’s one thing to be traveling, figuring out how to order food and get on a bus. It’s another to be living somewhere, with two highly dependent children and need to communicate complicated things with their doctors, their teachers, or the parents of their friends.

I had figured surely a few people would speak English; this was Europe after all. They didn’t. When we arrived, I had just enough language to irritate the cashiers at the grocery and initiate a conversation I had no hope of understanding, though I’d desperately nod and smile as though I did.

The solo I ended up choreographing was called “First Position.” There are five positions for the feet in ballet, and in those days I felt as if I couldn’t even make it to first. In the mornings, I struggled to persuade Molly to get dressed. The twos had been fine, but the threes, the terrible threes. Was it so hard because of the advent of a baby brother, or because of living abroad? Was she venting her frustration at being unable to communicate at home, where she could, rather than at school where she couldn’t?

I finally gave up and let her choose her own clothes, clashing reds and purples, and let her do her own hair. Who says there’s anything wrong with five sprouting pigtails? The Spanish, that’s who. The perfectly coiffed children with their perfectly coiffed mothersÔÇöin their neat but somehow so sexy business suits, with their matching, mother-daughter tucked ponytails clipped with starched bowsÔÇölooked at us appraisingly, or so I imagined, as I raced up to the school door each morning, dragging my crazily pigtailed child and carrying my about-to-be-deformed baby. Here we are, the Americans, a disheveled heap.

Those months in Andalusia went by in a sleep-deprived blur. But it was worth it. While I, at age 40, continued to struggle to read the labels at the grocery, Molly zoomed past us in Spanish.┬áThose months of playing color tag in the plazas and telephone at school taught her to spit out perfect Andalusian┬áth‘s and order lollipops at the ubiquitous candy shops using mysterious local slang.

In that astonishing way that kids can subconsciously absorb and sort out language, Molly would now have, for life, an ear for accents and the confidence that she could always communicate, first with that “you, meÔÇölet’s play” sign language and then gradually, magically, in a whole new verbal vocabulary. She’d found the key and unlocked the door just by osmosis; slipping in and bypassing all those torturous years of masculine/feminine nouns, single and plural agreements, past participles, conditionals, pluperfects, and subjunctives.

Last year, after graduating from high school, she decided to take a gap year to travel, by herself at 18 this time. Between working on an organic farm in Portugal and volunteering in a village school in Nepal, she decided to pay a visit to Cadiz.

“Mom and Dad, you won’t believe who I found!” she emailed us, her excitement palpable in the exclamation points. There was a photo attached. It was of herself and Ana, her preschool teacher at Arco Iris, standing next to a photo of Molly’s three-year-old self still hanging on the wall.

“We just cried and hugged and cried,” she reported. They were using that other language; the one that transcends words.

Meanwhile, Skyler became a great travel baby, happily carted onto buses to visit picturesque Spanish hill towns, onto boats to cross the Strait of Gibraltar, into oven-hot cars to trek into the dunes of the Sahara, and onto the string of planes to return home five months later. Who knows what his brain made of the wash of languages, but I think it can only have made his mind more supple. His turn to slip into a new language would come when he would be dropped into a local school in Brazil and, in the same miraculous way, pop out the other side, Portuguese verb conjugations and all.