Peter and I peered beseechingly into our toddler’s big blue eyes and handed her a spoonful of chocolate ice cream. We were getting desperate. Molly was onto us. We’d begun to feel like the Borgias, the wealthy and conniving Italian Renaissance family, plotting to poison a relative. Our efforts to bury her malaria medication in peanut butter, as we would for a dog, had failed. Not yet two, she was just under the 20-pound minimum for a full dose, forcing us to divide the tiny pill and release its acrid taste. Before long, we’d be leaving the relative luxury of Bali for the remote, malarial highlands of Irian Jaya (now West Papua). We wanted to be sure she was covered.

My family has a long history of carting babies to exotic places. My parents had moved to Bangkok when I was just three months old. My father, a foreign correspondent and journalism professor, had a yen for travel and saw no reason why children should slow him down.

“Start ’em young, get ’em hooked.” If he didn’t actually say it, this was clearly his theory.

I spent my first two years in Thailand, second grade in the Philippines, most of middle school in Egypt. After each adventure, our small family of three would settle back into our home base in Madison, Wisconsin. As an adult, I’ve found that despite losing my best friends every time I left to live abroad, I am grateful for this exotic, wide-ranging childhood—grateful for the curiosity it gave me, and the ease, the feeling that I could comfortably make my home anywhere.

My parents never openly articulated why they risked taking a three-month-old to live in Bangkok, a city with open sewers and snakes in the yard, where I would develop chronic diarrhea; or a six-year-old to Manila, where my mother and I cowered beneath our movie seats, hiding from the gunman who’d disrupted the Saturday afternoon matinee; or a twelve-year-old to Cairo, when Egypt had reached the height of its tension with Israel, and our apartment windows rattled from the bombs taking out planes at the airport.

But I suspect that deep down, they knew the risks would be worth it. Now, I’m convinced those early years of travel gave me the best parts of myself—the parts that can adapt, empathize, and connect. What I didn’t know at the time was that I was giving my parents something, too—that I was opening doors.

During that summer in Bali, Molly eventually retreated above the fray to perch on my husband’s shoulders, her face sore from the cheek-pinching, chin-chucking Balinese. Peter and I, however, tagging along on her coattails, had benefitted from preferential treatment we’d never experienced as pre-child adventurers. Balinese waitresses swept up to our tables before we could settle into the cushions to whisk away our blonde, blue-eyed wonder into the kitchen. Abandoned to our candlelit dinner amid wicker couches, clacking palm fronds, and intoxicating frangipani blossoms, we were served extra treats to keep us, and our child, there.

“Putu Molly!” they’d repeat gleefully as they disappeared with our daughter, following the Balinese tradition of naming all first-born children Putu.

We did have a moment of pause as we tried to visualize what gut-twisting morsel they might tempt her with —but only a moment. Subscribing to the theory that a few foreign microbes only strengthen the immune system, we felt comfortable enough. We’d also chosen Bali pretty carefully, as the perfect mix of exoticism for us and tourist-destination-based medical care for her—an equation we keep adjusting as our children grow.

But now we wanted to go further out, to hike in the Baliem Valley in the highlands of Irian Jaya. Another island in Indonesia’s vast chain, 1,330 miles east of Bali, it is home to many tribes, including the Dani. Chocolate ice cream had worked where peanut butter and pizza had failed, so with Molly primed we boarded the plane.

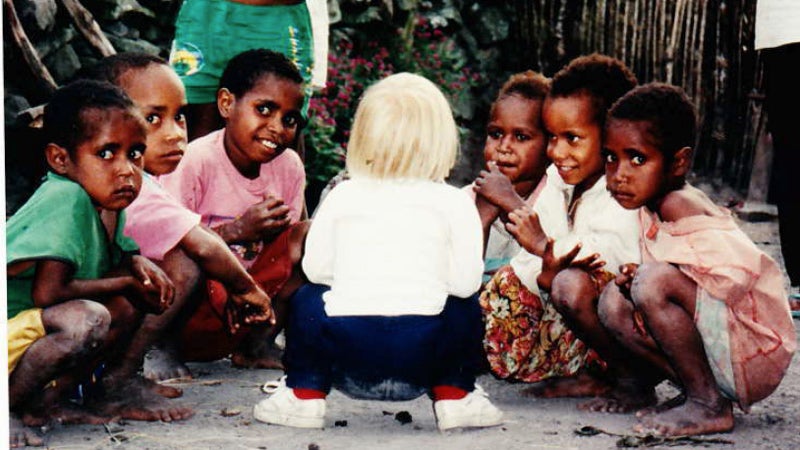

Several small-plane hops later we found ourselves trekking along worn dirt trails, following winding rivers through high, forested mountains. Molly rode happily on Peter’s back in a kid pack. Still nursing (useful in places where sanitation is questionable) she squealed with delight every time we passed yet another bare-breasted Dani woman. Headed out to steep hillside gardens to harvest sweet potatoes and cassava they all stopped to say hi to her. String bags woven of bark hung limply down their backs, suspended from forehead tumplines. A young girl held out her bag suggesting she could help us carry our child. Laughing she danced away with our strung-up baby on her back, Molly giggling in hilarity.

Small children are as magnetic as puppies, especially in the third world. For the next few days, we slept on straw pallets in windowless thatched mud huts; we bounced across suspension bridges and shared celebratory spit-roasted pig with men who were naked but for their penis sheaths (made of gourds, long and skinny for some, short and fat for others). Molly took it all in stride, unfazed by the bones through their noses, the feathers and paint on their faces. It was just another part of her growing understanding of the world. She hadn’t had time to start categorizing: this as normal, that as strange; this as comfort, that as hardship.

Although you might cringe at the thought of squeezing diapers into every available crevice of your backpack, although the responsibility of caring for a totally vulnerable, completely dependent creature in the outback might seem overwhelming, venturing into the wilderness with young kids is rewarding. Having them with us has opened doors into local lives that were never so easily opened before. And on the other side, our kids’ experiences of those lives have spurred on-going curiosity, tolerance, empathy, and general adventurousness—just what we hoped for in our children.

One doesn’t have to go to the highlands of West Papua to find great adventure with little ones. You can find it much closer to home, as we often have. But one thing is true no matter where you’re going: start ’em young, get ’em hooked.