“Come on. Right here,” the trip leader said, tapping his pursed lips. We were in the guide van on the way back to the boat house after guiding our last trip of the day down the Snake River’s Blind Canyon outside Jackson Hole, Wyoming.

“Kiss me,” he said, veering the van off the highway. “Show me you’re not a bitch feminist dyke.”

The long-ago scene was dredged from underneath my breastbone as I watched the hot-mic video of Trump rummaging around for a Tic Tac, claiming, “I’m automatically attracted to beautiful—I just start kissing them, it’s like a magnet—just kiss. I don’t even wait.”

The senior-guide and trip leader in the van didn’t wait, either. He just kissed me, spurred on by the complicit background sniggering from another male guide, a laugh almost identical to Billy Bush’s in the Trump bus video. I reminded my trip leader that I had a serious boyfriend in hopes that he’d yield, as Trump conceded he didn’t score only because “she was married, that’s why.” Consent never played into either scene. Consent was irrelevant.

***

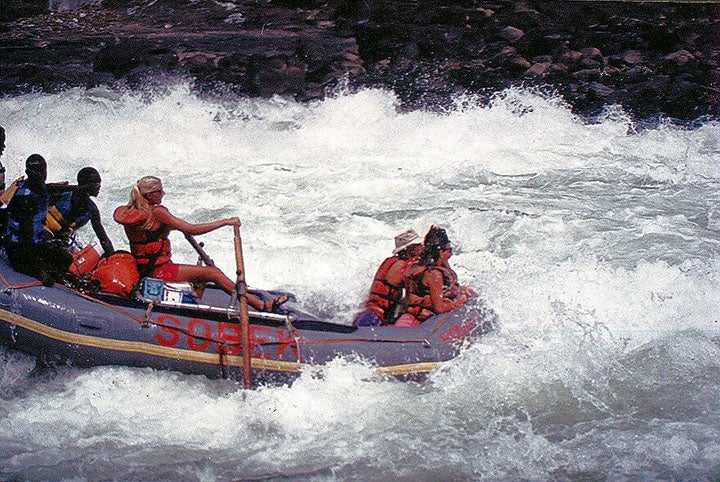

During my first season as a commercial river guide, along with ferry angles and highsiding, I learned how to navigate the relentless stream of sexual harassment braided into the culture of guiding. At 20 years old, I was no rookie: I’d been raised by guiding outfitter parents heavily involved in the environmental movement. At 17, I was sexually assaulted by an environmental activist friend of my parents—he pressed himself into my bed and grabbed what he wanted while saying he couldn’t help himself—I was just “so beautiful.”

Like Trump, he used a standard tactic for sexual predators to excuse the inexcusable: victim-blaming. His automatic attraction to “beauty” forced him to just start kissing me, without my consent. When I told my mother about the assault, she advised me to “Get used to it. It’s just going to keep happening to you.” I took my mother’s “get used to it” to mean “figure out some tools to live with and navigate it.” Like my PFD and ability to read maps, harassment-coping skills were necessary for my survival.

River Guides Have Long Faced Harassment

In January, the Investigative Report of Misconduct at the Grand Canyon River District went public, blowing the lid off the “long-term pattern of sexual harassment and hostile work environment in the GRCA River District.” Soon afterward, I contributed to a story for Men’s Journal about while working as a commercial river guide for 17 years on rivers throughout the Western U.S. and internationally.

In the story, I revealed how years before, I had faced retaliation for reporting a co-worker for sexual harassment. After his dismissal, I endured months of lecherous language and graphic pornography taped up in the guide van. These were men I considered to be close friends and allies, yet none of them stood up for me or called out the behavior as inappropriate. I understood that this was retaliation for ratting out a comrade, and that I was on my own. Going public with my story in a national magazine felt fraught with uncertainty and adrenaline, not unlike dropping into Lava Falls. Yet, the guiding and outdoor community came forward with tremendous support. I received many encouraging letters and calls thanking me for saying what needed to be said. I also heard from women who experienced similar harassment. It had forced some of them to quit guiding altogether. The outfitter I began working for hired three women in 1991 from its guide school (out of 12 new hires): one didn’t last the season, and one didn’t return for a second season. Why hadn’t I quit, too?

I grew up next to the Snake River, just upstream from Blind Canyon where my guiding career began. Since I was little, the river has been my refuge and protection—the place where I go when I’m beat up and broken down. It is the place where I am restored to the best version of myself.

Truthfully, this is why most guides are called to rivers and mountains. It’s our balm for a hierarchical society where many of us feel disenfranchised, anomalous, and unsuccessful. Nature is where we feel most empowered. We flee to the backcountry because it is largely untouched by society’s constructs, yet, rather than adjust to the ethos of nature, we bring our rank and file rules with us. Power gets abused, dominance plays out and spills into side-canyons and far-flung camps. Predators emerge.

As in nature, the answer to a healthy system is diversity. A quick look around the put-in, boat house or office confirms that guiding—and the outdoor industry—is overly male and overly white, as it has been since Lewis and Clark made their way to the Pacific Ocean. Ads and catalog images targeted at outdoor users are devoid of people of color and often cast women as yoga-hot-pants-clad props.

How the Outdoor Industry Can Make the Wilderness Safer

The outdoor industry can make positive changes by being more proactive about inclusion, making diversity in the wilderness the norm. Industry leader Patagonia, for example, regularly sponsors women-specific fly fishing events in partnership with local, grassroots fishing groups. Not only is this cultivating more women anglers, but more women anglers needing gear. Since beginning the clinics in 2013, their women’s fly fishing program has gone from a negligible percentage to accounting for 18 percent of the company’s total fly fishing business, according to Chris Gaggia, Patagonia’s global marketing manager for fly fishing. “We’ve included the voice of women anglers since our earliest fly fishing catalogs in 2000-2001,” Gaggia said, “which is right in line with Lynn Hill being such a vanguard of climbing. It’s just an extension of that.” Forward-thinking companies like Patagonia prove that extending a welcoming hand to women in the wilderness is not just good practice, it’s good for business.

Are we in the outdoor community ready to cultivate and realize a different future, one that stands up to the culture of sexual harassment we’ve allowed for too long? Or will we instruct another generation of daughters to get used to being objectified and harassed and another generation of sons to stand by silently while it happens? Our industry is filled with outside-the-box thinkers. If any group can lead the mainstream toward a diversified, healthy alternative to rape culture—that is, the culture of dominance and intimidation—it is us. We are the ones called to live on the edge, to find a line through seemingly impossible maelstrom. The line exists if we have the courage enough to drop-in. Fortunately, courage is something we possess in abundance.

Peter Heller, in his book Hell or High Water which chronicles the first descent of Tibet’s Tsang Po River, wrote, “A river’s last act is to empty itself of its self. How can you conquer something that only seeks to disappear?”

I would argue that the river doesn’t disappear, but transforms. She reinvents herself, adapting to the course ahead. When scouting rapids, the time comes when you can’t theorize and study the route anymore, you have to get in the boat and push away from shore. The moment when the boat leaves the eddy and crosses into the current is the moment of transformation—we leave what is comfortable in favor of what is possible. It is the moment whitewater guides live for, and it is the moment we must invoke now to heed the call of our highest selves going forward.

In the Trump video, Billy Bush posed the question, “If you had to choose, honestly, between us…” What do we choose? The systemic denigration of women that comes with “locker room talk” and behavior or a safe working environment where everyone is valued, empowered, and equal?