This story originally ran in the Summer 2020 issue of The Voice.��

A few years ago, as the trade war with China heated up, Mark Wolf decided he had had enough. Already frustrated with theft of his company’s intellectual property in China—Wolf makes outdoor fire pits, camp grills, and fireproof covers, under the name Fireside Outdoor, among other products there—he shifted production of a large chunk of the work out of the country, to Vietnam.

Then, last winter, the coronavirus hit. And Wolf, like many in the outdoor industry, felt just how inextricably his fortunes remain tied to China.

The contagion all but shuttered the country for weeks, including its border with Vietnam and the flow of raw materials and components Wolf required. “We had 13 containers sitting in Vietnam, stuck there. They were filled with kits waiting for nuts and bolts, the right fasteners,” Wolf, the president of Fireside Outdoor, said about his predicament at the end of March. All of those nuts and bolts come from China. What’s more, he says, the aluminum ingots his Vietnamese factory needs also come from China. “The coronavirus really exposed how dependent we are on China and their massive, disproportionate supply of raw materials,” he said. “And that’s the key: disproportionate. It’s almost like Napoleon realizing he’s too far into Russia.”

A reckoning is afoot, Wolf predicts. “We can’t all leave China in the short term,” said Wolf, who still makes 60 percent of his goods there. “But I can’t imagine there isn’t a boardroom in America that isn’t considering changing or offsetting their supply chain with China.”

China has long been the world’s workshop, producing one fifth of the manufacturing output across the globe, according to the Brookings Institution, a public policy nonprofit. Increasingly, however, many companies have been wondering whether China is still the place to make their products. Some companies already have shifted elsewhere, or plan to. Nearly 40 percent of respondents in an American Chamber of Commerce in the People’s Republic of China survey in mid-2019 said they had either relocated manufacturing from China or were considering doing so.

This conversation is “absolutely front and center” in the outdoor industry right now, says Drew Saunders, a member of the Outdoor Industry Association’s Trade Advisory Council and the country manager for Oberalp North America. Saunders knows from experience. He says that Oberalp’s brands—including Salewa, Dynafit, and Pomoca—have been making a “slow pivot” away from producing apparel in China over the last five years. For other firms, the U.S. trade war with China and now the global pandemic that has convulsed through China and the rest of the world have forced them to face the question: Is China worth the trouble?

The issue seems urgent amid the economic crisis ushered in by the coronavirus, but the truth is that other factors are at play, and despite the reasons to leave, there are also compelling reasons to stay. Here’s what the manufacturing landscape looks like—both in and out of China—and why the only certain thing is that this question is not going away.

The Case for Leaving

Rising Costs

Until recently, the primary issue pushing companies to leave China was simple: the increasing cost of doing business there. Once, cheap labor was a huge draw. That’s no longer the case: Hourly labor costs in China-based manufacturing reached $5.78 in 2019, according to Statista.com. In Vietnam, it was $2.99 an hour.

Wages aren’t the only rising costs. The Chinese government has imposed increased regulatory requirements, and costs related to the environment have risen as well, as the country tries to address major pollution problems. “You can’t just dump stuff anymore,” said Mary Lovely, a professor of economics at Syracuse University and a senior fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics. Outdoor companies are all for reducing pollution, of course, but it still changes the cost of doing business.

Sitting like a sour cherry atop these varying concerns are the tariffs of the U.S.-China trade war. Those costs are driving Fishpond USA to seek manufacturing elsewhere. Fishpond has successfully relocated some of its softgoods production, but still has significant ties to China, says founder Johnny Le Coq. “Oh yeah. We’re looking. We’re looking at every opportunity we can, for the factories who have the ability, from a quality perspective, to make our products,” he said. “Our duty on packs and bags made in China is now over 42 percent, up from 17.6 percent just a few years ago.”

That extra cost creates another frustration, Le Coq says. “With reduced margins, the incentive to innovate within that category is reduced and compromised. And we live in a world of innovation.”

That leaves few options, Le Coq said. “The implications of the tariffs are forcing brands like us to move.”

Human Rights

Concerns about working conditions in China are hardly new (see: Apple and FoxConn). Human rights violations aren’t, either. But a report released in early March now links these two in a troubling way. The Chinese government has transferred Uyghurs, a Muslim ethnic minority, and also other ethnic-minority citizens, to factories across the country and is making them work “under conditions that strongly suggest forced labor,” according to the report “Uyghurs for Sale” by the Australian Strategic Policy Group, an independent, nonpartisan think tank. The Uyghurs are in the supply chains of “at least 83 well-known global brands in the technology, clothing, and automotive sectors,” the report alleges, citing Apple, BMW, Nike, Patagonia, and L.L.Bean, among others.

In reply, companies told media outlets they take an ethical supply chain seriously and are committed to upholding compliance standards that prohibit forced labor. Patagonia and L.L.Bean both issued statements affirming this, with L.L.Bean saying, “Our Supply Chain Code of Conduct strictly prohibits the use of forced labor of any kind. Our global compliance programs and auditors cover every country where a factory makes L.L.Bean-branded product, including China, and we are actively working with our fellow industry leaders, associations, and our partners in the region to ensure that our supply chain standards are being met at the highest level.” Amy Celico, principal at global business consultant Albright Stonebridge Group, expects this issue will continue to be a big deal in the coming months. Some companies will decide remaining in China is not worth it, she says, given the need to police supply chains.

Emerging Alternatives

While forces within China are pushing companies out, there are opportunities elsewhere that are pulling them in. For example, skilled workers in other countries are drawing brands that need cut-and-sew manufacturing.

Vietnam is one of those places. Osprey discovered it years ago, and recently the ski glove maker Hestra USA followed suit. About three years ago, the company purchased a building there and installed new equipment, as part of a long-range plan to shift part of its glove production from China to Vietnam, says Dino Dardano, the company’s president. “We’ve had tremendous success—so much so that we actually expanded the facility by about 30 percent last fall to accommodate about 125 more workers,” he said.

Dardano says Hestra has been in China for 50 years, owning two companies there in a joint venture. But experienced sewers are in decline there, and the company has not found young people to replace them. “I can tell you that I’ve had a lot of conversations with my peers and they’re faced with the same challenges when it comes to sewn goods,” he said. Dardano attributes the change in part to China’s now-defunct one-child policy, and the problem is likely exacerbated by the natural evolution of a maturing economy.

Vietnam isn’t the only country benefiting from the exodus. South Asia saw a 34 percent increase in demand for factory inspections and audits in the first half of 2019 over the same period in 2018, according to supply chain consultant QIMA. And the migration is not limited to Asia. Tariffs and the coronavirus have also made it more appealing to bring production closer to home. The volume of inspections “As a company has no plans to move production and audits ordered of factories in Latin America by U.S. businesses increased nearly 50 percent last year,” QIMA reported.

Another shift away from China came at the prompting of the outdoor industry itself. Travel goods—luggage, backpacks, sports bags—made in China can be taxed steeply upon entering the U.S. Sensing opportunity, the outdoor industry lobbied to have such goods made eligible for the Generalized System of Preferences (GSP), a trade-preference program that allows qualified products to enter the U.S. duty-free when a substantial amount of their value is produced in more than 120 developing countries. The effort has been successful in recent years. “Since that went into effect, we’ve seen a movement out of China to Indonesia, Philippines, Thailand, and other GSP countries on travel goods,” said Rich Harper, manager of international trade for Outdoor Industry Association. In 2015, China produced about 64 percent of GSP-eligible travel goods. By January of this year, that share of “made in China” had been cut by 40 percent. “The duty savings that first year was something like $90 million” for outdoor companies, Harper says.

A Natural Evolution

What companies are experiencing overall with China is part of a natural evolution: As a country matures, so does the nature of the work that’s done there. You can see the Chinese government directing this transition, says Celico, of the Albright Stonebridge Group. “As the country has become more economically advanced, it’s not just that it became more expensive to manufacture there, it’s that the Chinese government started to—sorry for the lack of a technical phrase—pooh-pooh low-end manufacturing,” Celico said. “The government has started to become more selective about the kinds of manufacturing it wants to encourage, as well as the location of manufacturing facilities.”

Celico recalls working with a sporting goods manufacturer there. Government officials told the company they didn’t want the factory in the middle of Shenzhen anymore because the area was being turned into a high-tech manufacturing zone. “We just decided that if we’re gonna move, we’re gonna move to Mexico,” Celico said.

This evolution has played out elsewhere. Japan, for instance, became the place to produce cheap goods right after World War II, and was later supplanted by Taiwan. Eventually manufacturing went to places such as Korea. Thirty years ago, South Korea was the world’s primary supplier of backpacking tents. Now it supplies the high-end fabric and poles for those tents, but the tents themselves are made elsewhere. Today, South Korea has a booming outdoor recreation scene and its participants now buy those tents.

The Case for Staying

Quality and Capacity

Despite qualms about China, many outdoor companies say it’s not good for business to leave. For starters, the work is usually fast and high quality. Of course, not every company’s experience in China is the same because not every supply chain is the same, says Lovely, the economics professor. Small companies that don’t require much sophistication, or don’t need many subcontractors to make their products, can pick up and move rather quickly in the face of headwinds, she says. Meanwhile, very large multinational companies (Samsung, for example) may be able to shift production to another factory they own elsewhere, if trouble strikes. But a lot of outdoor companies probably fall in between the two, she says. Their products require knowledge to make, perhaps specialized equipment and techniques, a mature supplier system, and contractors and subcontractors. Finding this elsewhere is not easy, she says. That makes China “sticky,” as it were.

Big Agnes manufactures throughout Southeast Asia, including in the Philippines for furniture and, more recently, in Vietnam for stuff sacks. But the Colorado-based company has no plans to move production of its well-regarded sleeping bags and tents, the latter of which can command $700 or more, out of China, says founder Bill Gamber. “The best sleeping bag manufacturers in the world are in China. Same goes for tents,” Gamber said. In 2019, 95 percent of all down sleeping bags imported to the U.S.—and nearly 90 percent of all kinds of sleeping bags—came from China, according to statistics from the International Trade Commission.

Relationships

More than a physical factory and skilled workers keep Big Agnes in China, however. “A really high-end, ultralight backpacking tent is not as complicated as an electric car,” Gamber acknowledged. “But our supply chain is very specific for building a very specialized tent.” Big Agnes’s manufacturer leans on an ecosystem of suppliers. “We’ve been working with both our factory and fabric supplier for 20 years,” he said. “It would take years to rebuild what we’ve done.”

Such talk of “relationships” is not mushy sentiment; a relationship can save you money, says Gail Ross, chief operating officer of Krimson Klover, whose apparel company continues to work with the same factory in China that it has for a decade, even as some of the brand’s manufacturing of sweaters and other clothing has shifted elsewhere. “I can say, ‘Hey, do you remember that silhouette from five years ago? I want you to haul that out, and do this, this, and this with it,’” Ross said. Less back-and-forth with a factory owner translates into less time and money spent air shipping prototypes. And a longstanding relationship means Ross only goes to the factory in person twice a year. “With brand-new factories, we need to go three, maybe four times a year.”

A small company like Krimson Klover also found something else when shopping around for alternative manufacturing options: “There are other countries—Indonesia, Vietnam—that are really great at cut-and-sew and printing. But the minimums are much higher,” Ross says. So, for now, the same Chinese factory that gets the “carrot” of her fall business is willing to accept the “stick” of her tiny spring production.

Culture

And then there are cultural differences that can work in China’s favor. In China, “a normal shift is 12 hours,” said Wolf of Fireside Outdoor. “They work seven days a week. And then they really, really enjoy their holidays.” He added, “What we’re seeing in Vietnam, and we also saw this in the Philippines, is that they have a different work ethic. In Vietnam we’re having challenges where an employee won’t show up for three days. Then he just shows up on the fourth day and says, ‘Here I am.’ It’s hard to do a production line when someone doesn’t show up at their post.”

In China, workers historically have been more willing to move where the work is, says Neil Burch, who has 35 years of experience manufacturing in Asia and today is president of the North American group of Joinease, which designs, manufactures, and does market research for drinkware for the suppliers to Nike, Gatorade, and Brita. “But in Vietnam, they kind of want to live at [or near] home,” he said, which can cause issues for manufacturers in locating and moving factories. Burch says his company has looked at Vietnam, and could establish a factory there eventually. But not yet.

And China is not alone in wrestling with issues of human and workers’ rights. Ethical ratings in Malaysia, Vietnam, and the Philippines have been “slipping,” according to the consultant QIMA, and factory safety can be poor. (One outdoor company executive says she wasn’t comfortable leaving China for another country, where working conditions and human rights would be even harder for her to track.)

For his part, Burch’s company is refocusing on China. “We’re looking at doubling down and reinvesting,” he said.

Emerging Middle Class

An enormous reason to stay in China is the Chinese market itself. “China is poised to replace the United States as the biggest consumer market in the world,” said Celico, from the Albright Stonebridge Group. “That is a massive change. This is a country of 1.4 billion people. The middle class is basically larger than the population of the U.S.” China has a thriving outdoor gear market. It was worth $60 billion in 2018, and it’s expected to be worth $100 billion by 2025, according to a 2019 report by Research in China.

“And so, what a lot of companies are doing is sort of splitting the baby, saying, ‘OK, maybe we have to diversify our global supply chain, but we still have to manufacture inside China, for China,’” said Celico.

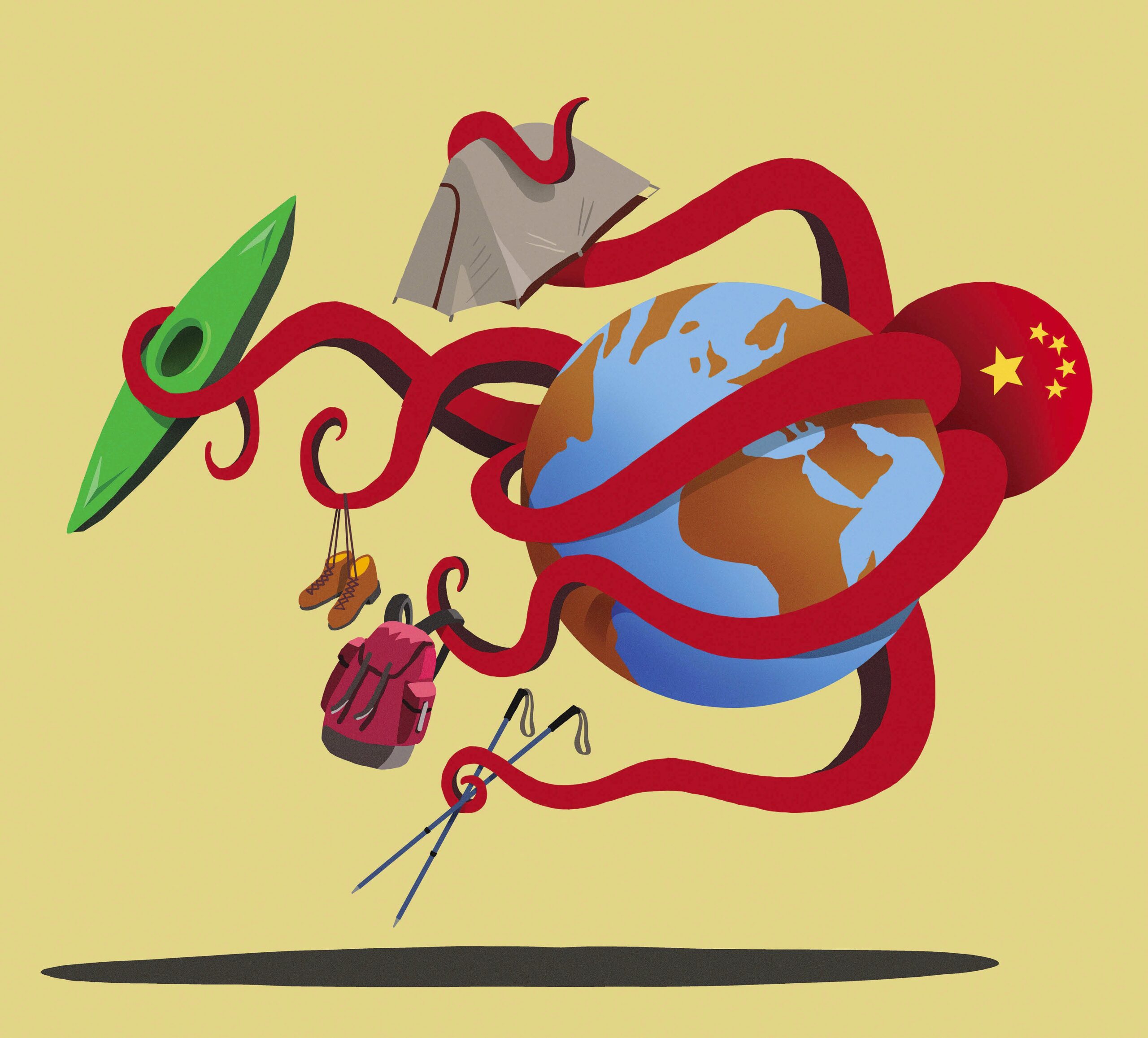

To Leave or Not to Leave

Every company will use a slightly different calculus to determine if it’s time to go. And many will find, like Wolf, that even when you decide to get out, truly disengaging from China is harder than it appears. But every company will have to confront the same basic issues, and this unavoidable fact: The worldwide ecosystem of manufacturing and consumer sales is more complicated, and more intertwined, than ever before. China is at the center of that world and no matter what you make or where you make it, managing how the global Goliath impacts your business matters more than ever.