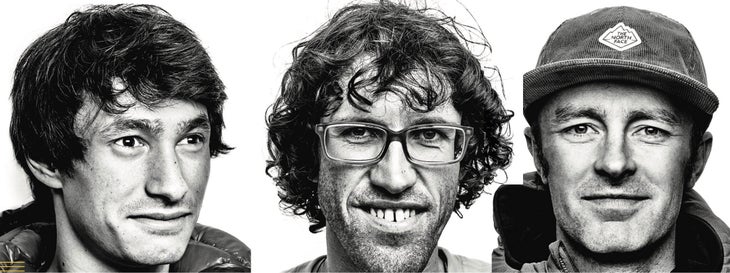

On April 16, 2019, David Lama, Hansjörg Auer, and Jess Roskelley died in an avalanche on Howse Peak in the Canadian Rockies. All three were on The North Face climbing team.

At the time, the trio was seeking the second ascent of a route called M-16, which had been climbed once, back in 1999. The first ascensionists described pitches of overhanging ice, blinding spindrift, and collapsing cornices that nearly killed one of their party.

But in alpine climbing, unrepeated routes are rare trophies, and Lama, Auer, and Roskelley were some of the best in the world. Why wouldn’t The North Face give them its blessing? And perhaps the brand was right to do so; according to photos recovered from Roskelley’s phone, the three made it to the summit. That was before the avalanche.

When I heard the news, I grieved with the rest of the climbing community. In the past few years, I’ve lost two friends to the mountains. This tragedy felt too familiar.

I wondered if Lama, Auer, and Roskelley would have chosen to team up if it weren’t for the convenience of sharing a sponsor. If they would have picked a less hazardous route if they hadn’t been vying with other athletes for The North Face’s limited pool of funding. If they would have turned back earlier had Roskelley and Lama not been so new to The North Face’s team—only about a year each—and perhaps still trying to prove themselves. If they would have called it sooner if not for the expenses already incurred.

Hadley Hammer, Lama’s girlfriend and an eight-year member of The North Face ski team, believes Lama’s motivations on Howse Peak were purely intrinsic. The North Face global sports marketing director Jamie Starr added that, for many years, the brand has had a rigorous team peer review process for expeditions and is careful to never put any external pressure on athletes to take undue risk—including on Howse Peak. Still, these are familiar worries for many athletes. And there are other concerns with the current sponsorship system, particularly for winter ambassadors who have only a short season with uncertain conditions to accomplish many contractual obligations, Hammer said.

“Two of my three injuries occurred while filming,” she explained, noting that it’s impossible to say whether they would have happened without a camera present. Both injuries left her with medical debt, which she was left to pay on her own. “While there isn’t direct pressure to perform crazy stunts, there remains an inevitable pressure,” she said. “And I don’t think it has to be that way.”

When these three men died, The North Face, by all accounts, rose to the occasion, footing the bill for loved ones’ flights and travel expenses. Providing therapy and support. Paying for the funerals.

None of this was required—athlete contracts rarely mention, let alone cover, such expenses. And all of it is certainly costly to a brand. The North Face stepped up, said Hammer. It did the right thing, handling it all in just the right way.

But while members of The North Face team certainly grieved, the brand, through no fault of its own, ultimately emerged looking like a hero, its reputation untarnished.

Stories like this highlight the imbalances that exist in the sponsorship equation. Today, controversy accompanies everything from how athletes are selected, to their role in hitting a brand’s DEI targets, to the contracts they sign. As that equation becomes more critical to the success of outdoor brands, it may be time to rethink it.

A Broken Model

When news broke of the tragedy on Howse Peak, Horst Eidenmüller, a law professor at the University of Oxford, was in the midst of examining some of the same questions about the hidden pressures athletes face. In August and September of 2018, he conducted interviews with 40 sponsored athletes across a range of adventure sports, from alpine climbing to big-mountain skiing to freestyle motocross, and later published his findings in the Marquette Sports Law Review.

Eidenmüller’s conclusion: “These contracts are unbalanced,” he said. “Sponsors—let me be blunt—they are ripping off the athletes.” The trouble is that athletes are easy prey; most interviewees told Eidenmüller that they’re more passionate about their sports than they are about money. That lets brands get away with paying them, on average, $5,000 to $20,000 a year for what often amounts to a quarter- to half-time job. That’s barely enough to cover their training, health care, avalanche education, and other expenses. Even top-tier athletes like Alex Honnold, who make salaries somewhere in the six-figure range, are a steal, Eidenmüller said.

That’s because marketing today relies heavily on personality, dynamic storytelling, and dialogue, explained Jonathan Retseck. Retseck is a founder and managing partner of talent management firm RXR Sports and represents an impressive roster of outdoor industry bigwigs, like Jimmy Chin, Alex Honnold, Scott Jurek, and Kate Courtney. “We’re also seeing more and more consulting work integrated into [athlete] contracts,” Retseck added, explaining that brands increasingly rely on athletes to help develop new products, provide design input, and shape marketing campaigns. “All of that is extremely valuable to a brand.”

Just how valuable? From his analysis of annual revenues and marketing budgets of some top sponsors, Eidenmüller estimated that big international brands are making as much as millions of dollars in additional revenue from their household-name athletes. Compared to that, he said, even a six-figure salary is a paltry sum.

“The picture that emerges is that of a market tilted heavily towards satisfying the interests of the sponsors,” Eidenmüller said.

Thanks to the COVID-19 boost, the outdoor sector is booming. That influx of revenue has allowed more brands to create athlete teams or expand existing ones. And thanks to the recent push for brands to improve representation of diverse adventurers, athlete teams have been hauled even further into the spotlight.

After all, athletes are the faces of a brand. They’re also usually inexpensive, on short contracts (typically just one to three years), and easy to turn over to meet the needs of the day.

According to two former La Sportiva athletes who asked to remain anonymous for fear of being passed over for future sponsorships, La Sportiva dropped about half its North American athlete team—close to 45 people—earlier this year via a mass email. A number of the new 2021 La Sportiva athletes are people of color and best known for being outspoken on social media on issues of race and social justice.

“We reviewed our current situation and future plans and ultimately made some tough calls,” said Quinn Carrasco, marketing manager for La Sportiva North America. “It’s been a huge learning process.” The brand primarily offers athletes one-year contracts, requires regular social media posts in exchange for gear, and offers no monetary compensation to most ambassadors. La Sportiva dropped a similar percentage of athletes in 2020. Carrasco said it’s hard to let ambassadors go but that turnover is an inevitable part of any athlete program and will naturally fluctuate from year to year.

Steve House, a legendary alpinist who now consults for brands building athlete teams, explained that this high-quantity, high-turnover system does make sense for some brands.

“The thing is that you have no idea who’s going to pan out,” he said. “You have 100 athletes and one of them is going to be Alex Honnold, and you have no idea which one.”

Mentorship Over Sponsorship

Scarpa CEO Kim Miller, who is Asian American, also noticed a hole in the demographics of Scarpa’s athlete team in 2020. But for Miller, the answer wasn’t to bring on a host of green, unvetted athletes.

“The first thing I realized was that there just aren’t many people of color in our outdoor sports, industry, and community,” Miller said. “And the second thing is that you can’t just walk into a field and say, ‘Grow, plants, grow!’ These things really have to be developed.”

For Miller, the answer was to start a mentorship program for up-and-coming athletes. The program would allow the brand to both maintain existing relationships with its athletes and give new athletes the resources they need to navigate the industry, advance in their respective sports, and market themselves effectively.

Called the Scarpa Athlete Mentorship Initiative, or SAMI, the six-month program matches each mentee with an existing Scarpa athlete. It also provides mentees with gear and networking opportunities. However, mentees aren’t required to use or post about Scarpa gear; there are no strings attached, Miller explained. “This was never about creating more athletes on our team.”

Aidan Goldie, a science teacher, ski mountaineer, and diversity advocate based in Carbondale, Colorado, was selected as part of the inaugural SAMI class. He and his mentor, Chris Davenport, ski together and text on a regular basis.

“It’s a really intentional program that makes sure these athletes from diverse backgrounds are set up for success,” Goldie said. “It’s given me a lot of connections in the industry. And Chris has been a great resource.”

The mentorship program, he said, is doing exactly what it set out to: bridge historic inequities by lifting new voices up.

The Third Model

Over the past year, a third model of sponsorship has emerged: eschewing the somewhat elitist idea of the athlete altogether and instead sponsoring changemakers from diverse backgrounds who can speak to new audiences and untapped markets.

Backcountry pioneered that model when it launched its Breaking Trail program this April. Instead of scrambling to start new relationships with people of color, which could come off as tokenizing, the brand moved to sponsor seven prominent advocates and community leaders with whom it had already built close relationships.

While plenty of outdoor brands had partnered with culturally diverse advocates for occasional campaigns, this reimagined take on sponsorship broke new ground. Ambassadors were selected not based on past ascents or expeditions, but on their nonprofit involvement. And the brand intends to add new ambassadors and build upon the program in the future.

Diversity Without Exploitation

Widening the definition of who can be a sponsored athlete is certainly a big step when it comes to inclusivity, but it doesn’t solve the power imbalances that Eidenmüller uncovered in his research. And some athletes believe the shift could exacerbate those imbalances.

After all, the current structure tends to provide less compensation to athletes who “achieve” less. But today, the role of an athlete isn’t just to tag summits, and some, like Andrew Alexander King, worry that the other, equally important work will go undercompensated.

King, who is African American, is a sponsored mountaineer pursuing the Seven Summits.

“I think athletes of color are often taken advantage of,” he said. Part of that is because, due to historic inequities, athletes of color are less likely to have had the resources to understand how the sponsorship system works and negotiate effectively. “Think of it like a race,” he said. “Athletes of color have been standing outside the stadium, and the world has just let them in. But the race has already started, and by now, an athlete of privilege is already two laps ahead.”

In that sense, if the athlete is climbing or skiing at a lower level than an athlete from a privileged background, it’s perfectly reasonable, and shouldn’t result in fewer opportunities.

Plus, there’s the matter of supply and demand, King said. Athletes of color are few and far between, and right now an image of a Black man climbing in branded gear is extremely valuable. Many boilerplate contracts, which include lifetime licensing for images, don’t reflect that. So, when King talks to a potential sponsor, he starts by demanding changes.

“You can have my photos for one year,” he said. “Any time after that you have to re-sign or go through contracts. If you put my face up in 2023 without my consent, you’re profiting off that, which is exploiting my story and my culture to benefit your profits.”

Brands, he said, would do well to listen. Or, better yet, offer athletes of color what they’re worth in the first place.

Calling for Change

King’s negotiations often catch sponsors by surprise. That’s because, Eidenmüller said, brands hold all the power in those conversations; they’re not used to negotiation.

Mentorship, à la Scarpa’s SAMI program, could help bridge that power gap and give young athletes the tools they need to negotiate with confidence. More transparency around contract terms and salaries, which are currently guarded as “proprietary,” would also give athletes and brands the information they need to reach fair terms.

While Eidenmüller believes athlete contracting would most benefit from regulatory oversight, he said the faster, more practical solution is for brands to take responsibility for the outsized power they hold over athletes. The onus should be on them to carefully spell out all the implications for new athletes or ambassadors, and to offer the stability of longer contracts, increased and stable financial compensation, and/or health insurance whenever possible.

Where the Responsibility Lies

As for limiting risk?

“I think athletes bear some responsibility to know their own limits, and to know them before they’re in a place where those limits are being tested,” Hammer said. “Plus, it’s the athletes [who are] coming up with these ideas. We’re asking the brand to support us. Even if The North Face or other brands scaled back [on their interest in dangerous expeditions], I don’t know if we would.”

Difficult realities are easier to absorb if we have someone to blame. Preferably, a faceless entity with deep pockets. But deep down, I know Hammer is right.

At least one of the friends I lost in the mountains was chasing a personal speed record at the time of his death. Eventually, he hoped to be sponsored. But both friends had gone out, first and foremost, in search of the sublime. In a world without funding, social media, or external gratification, they would have done it anyway.

As La Sportiva’s Carrasco said, “Ultimately, our goal with sponsorship is just to align projects—we want to work with people who are highly motivated. When our goals align with theirs, that’s when we can help each other out.”

But even if brands don’t push their athletes or demand certain objectives, they are still in the business of selecting and paying people with enough passion and grit to push those limits. For that reason, contracts need to clearly stipulate who is responsible when the worst happens, Eidenmüller said. If someone gets injured or sick, how long until they have to be performing again? If someone dies in the mountains, who foots the bill?

The Future of Sponsorship

As brands get bigger and add to their athlete rosters, more people than ever before will be sponsored in some way, Eidenmüller said. The market will grow more competitive as it crowds with voices talking up their own achievements—and more jaded as audiences wisen to influencer marketing, which right now, House said, is likely coming off the peak of its popularity.

“I think the reality is that social media influencers don’t have much influence,” he said. “Audiences today can see right through those sponsored posts. The reality is that they just don’t work.” In the future, he expects the age of the social media influencer to fizzle, and for authenticity to once again dominate the playing field.

This presents a golden opportunity for brands to get ahead of the shift and select athletes who are both champions of their sport and genuine pillars of their community—not just salespeople. To do that right, they’re going to need to allocate more marketing budget to find the right ambassadors, build quality relationships, and compensate them like they would any other employee, said King.

Quality over quantity—in how athletes engage with their communities and how brands treat their ambassadors—is about to become the rule of the day. And the brands that figure that out fastest will come out on top.