In an Oregon thrift store one afternoon more than 20 years ago, Bruce Johnson found a vintage Trapper Nelson pack hidden in the racks of secondhand clothing and accessories. He bought it, took it home, photographed it in his studio, and dug up the company’s history dating back to the 1920s. His findings and photographs are still documented on a website he created in the mid-1990s to share details about the outdoor industry’s origins and founding companies like Frostlines, A16 Packs, Wilderness Experience, and Kelty.��

A diehard outdoorist and gear enthusiast, Johnson has boxes full of papers noting important conversations, factoids, and other interesting pieces of the outdoor industry that he’s been collecting since the mid-90s. He’s motivated by nostalgia, but also a sense of practicality and remembrance.

“There are still so many lessons to be learned from the past,” Johnson told ���ϳԹ��� Business Journal. “I just put my material [online] in hopes that it will inspire people to look beyond just the immediate moment.”

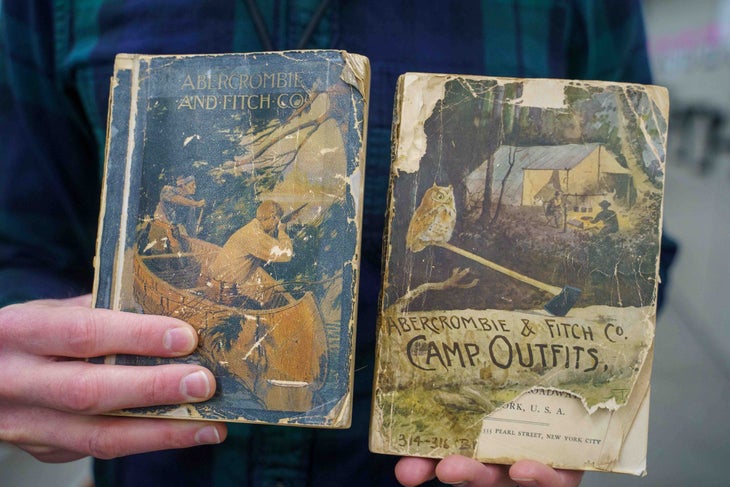

Across the industry, educational institutions and folks like Johnson have been collecting documents, gear, memorabilia, journals, photographs, and other seemingly mundane keepsakes for decades for just that reason—so people today and years from now can fit the pieces of the outdoor industry puzzle together.

Keepers of the Archives

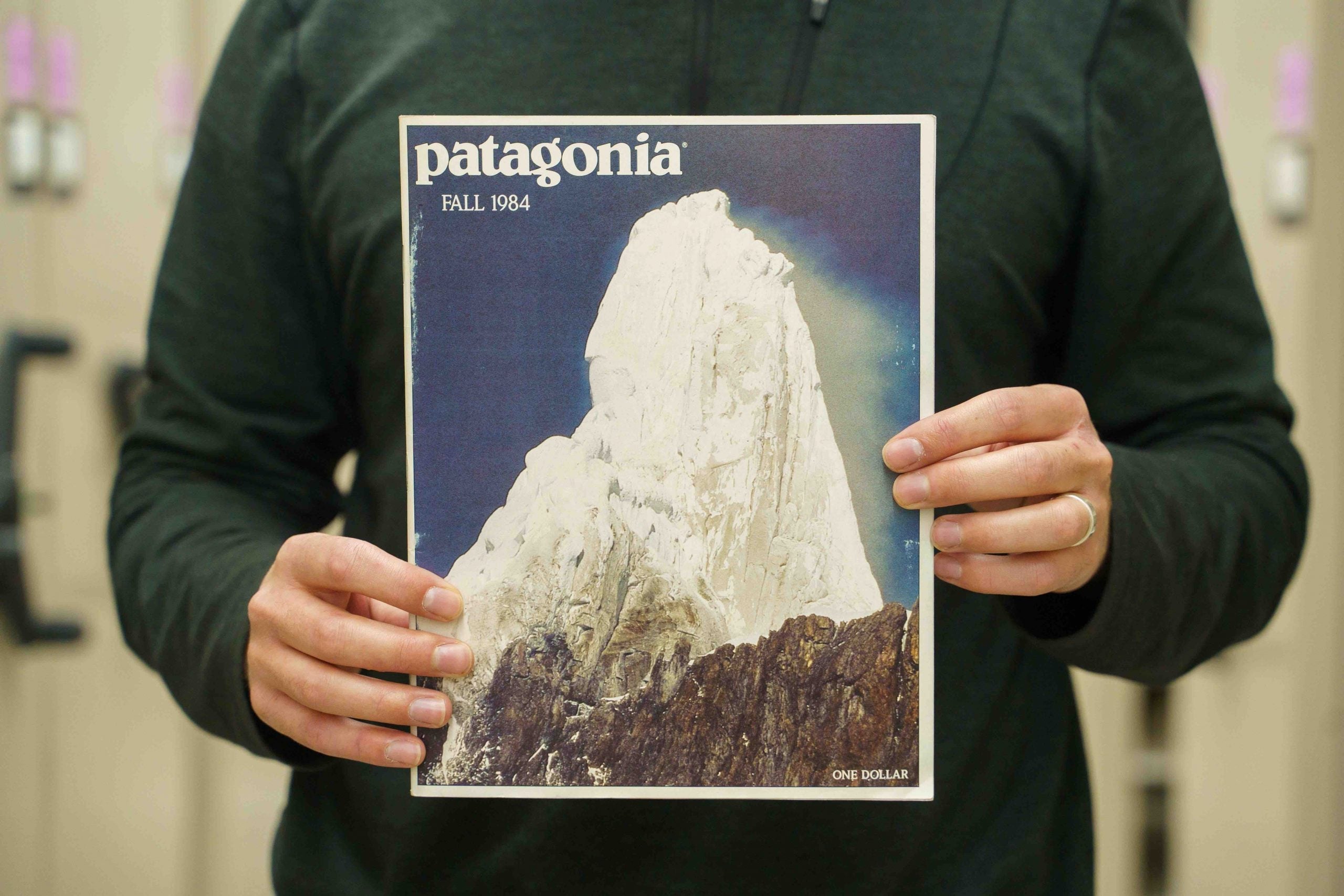

Opened in fall 2019, Utah State University’s Outdoor Recreation Archive was created to serve students in the Outdoor Product Development and Design program. But enthusiasm in the library extends beyond campus. Today, the archive preserves 3,000 outdoor brand catalogues from 400 companies (Patagonia takes up majority of the space) and nearly 6,000 outdoor magazines from 70 publications. More items get added every week, like a Snow Lion poster from the 1970s that manuscript curator Clint Pumphrey unfurled one day in May. Archives are different from museums in that they deal mainly with two-dimensional materials rather than artifacts. The archive in Utah includes very few pieces of gear.

“I always say an archive is like a museum where you can actually hold the materials and look through them,” Pumphrey said.

The online and physical collection is completely open to the public, and it has been used by international students, graphic designers, gear collectors, and researchers. One such researcher who has accessed the archive is Rachel Gross, an environmental and cultural historian writing a book slated for 2023 called Buckskin to Gore-Tex: The Outdoor Industry in American History.��

Gross is one of a handful of people analyzing, critiquing, and making sense of the outdoor industry’s storied past. She is specifically examining what kinds of meanings Americans associate with outdoor gear and what they think those goods say about their identities. Her work hinges on the preservation of records by libraries and other institutions.

“I can only write about things that exist in some document somewhere, otherwise I won’t know to even search for them,” Gross said.

For some people with extensive personal collections, such as former employees or company leaders, it’s sometimes just stuff in old boxes. It holds meaning to them, but they don’t think it will for anyone else. Roger Poor, who worked at L.L.Bean starting in the 1970s, is uncovering the significance of those items by talking to old friends and colleagues with institutional knowledge to piece together a book about the stories behind the logos.

“All these things had a place in the birth and evolution of an industry that’s very much alive and thriving everyday worldwide,” he said.

While oral histories, books, personal blogs, Utah State’s archive, and museums like the Smithsonian exist for the benefit of the public, corporate archives are oftentimes harder to access externally—yet essential stories exist behind those walls.

The Business Sense of Corporate Archives

By the 1980s, Eddie Bauer had been in business outfitting mountaineers and other rugged adventurers for more than 60 years. Leadership decided that many of their past products were objects of value and started organizing some of the pillar pieces into a more formal archive. Colin Berg started his career at the company as a writer in the 1990s, but his deep interest in EB’s storytelling potential eventually landed him the position of official brand historian. After leaving for a short time, Berg was tapped again to preserve the pieces of Eddie Bauer’s history when a new CEO, Neil Fiske, took over with a mission to make the archives accessible not only to employees but also to vendors and fans of the brand.��

For a few years during Fiske’s time at the helm, part of new employees’ interview process was to step inside the showroom that’s still set up as a mini museum displaying vintage garments, Eddie’s journals, and letters from customers.

“They were required to have an hour-long tour of the archives with me,” Berg said. “It was a way of immersing them in the brand, but also seeing really clearly that they were resonating with who we are.”

Even after more than two decades combing through boxes of items, Berg still gets emotional over certain finds, such as a heartfelt letter written to Fiske by a longtime customer after the company filed Chapter 11 bankruptcy in 2009.

“It’s not just about the company, it’s about the community,” said Berg.

Other legacy companies with known corporate archives include Patagonia, Gore-Tex, and Red Wing Shoe Company, which use their libraries to inform future designs and inspire employees.��

Berg said an archive is like a mirror, revealing a brand’s past as well as its soul and DNA. It’s also like a window to the world to reveal the brand to customers. “Without this kind of reference, it’s very easy for a brand to lose its way, and difficult for it to get itself back on track,” he said.

“You have to know where you’ve been to understand where you’re going,” said Clare Pavelka, Red Wing Shoe Company’s historian and the communications representative for the corporate archives. Vasque’s parent company frequently uses historical materials from the 20th century in marketing campaigns to bring validity to the footwear brand, but it isn’t open to the public.

In some cases, corporate archives are like a family’s secret recipe. They can store proprietary information that made the company what it is today, if it’s still in existence.��

Shortcomings of Preservation

Mainly due to lack of space, it’s impossible for historians and archivists to hold onto every single item. Many pieces get tossed. “The decisions we make on a daily basis impact the sorts of materials that are available to people and researchers in the future,” said Pumphrey.

He said that in the 1950s, historians prioritized records from the rich and powerful—mainly white men—thinking they were doing the right thing at the time. But professionals today have since recognized the fault. They now strive to collect items that reflect the diversity of the people involved. When choosing what items to include in the Special Collections, Pumphrey checks his gut by asking himself, “How important is this item to telling the story of this industry?” He has kept everything from internal company emails and newsletters to vintage posters and old photographs of prototypes.��

“It’s hard to gauge what materials or stories will end up being important or what questions future historians will ask of all of us,” said Gross. “We often discount the minutiae of our lives as unimportant, but we don’t know yet what they’re emblematic of.”

But despite best efforts, the puzzle will never be entirely complete. For one thing, the industry’s first backpacks, tents, hiking boots, and other pivotal pieces aren’t centralized in one single place. Gear is spread across the world, kept in individuals’ basements and gear closets. It’d be a monumental undertaking for Utah State to take on the responsibility, Pumphrey said.

Another shortfall of an archive is its timeline. Historians like Gross agree that the business side of the industry is at least 100 to 150 years old. However, people point to the 1960s and 1970s as outdoor recreation’s first big boom, when sleeping outside became a thing of leisure rather than a necessity.��

But Dewayne Dale, a footwear designer and member of the Navajo Nation, looks to his ancestors from thousands of years ago as the trailblazers of technology in the outdoors.

“I would go back 500 years,” Dale said. “A lot of tribes were doing a lot of cool things with products at that time, most of them being handmade.”

Using the Past to Inform the Present and Future

Sure, collectors get a rush from holding a backpack made by its original inventor or one that they took on their first overnight trip. But the significance of intentional collecting is to re-create and recognize the past.��

For Gross, her work connects the dots between past and present hikers, backpackers, climbers, and whoever so they can better understand themselves and the role gear consumption plays in their lives. And by making those connections, she hopes the individuals at companies can better understand the histories and myths of the centuries-old industry to inform marketing decisions.

“I don’t think people would peddle myths of the frontier quite the same way if they understood this history of racial violence against Native peoples,” she said. “I don’t mean we shouldn’t buy tents. But rather, we are cognizant of what certain ways of selling a tent connote.”

At Utah State, future gear designers will look to the Outdoor Recreation Archive during their studies. So will current product innovators, gear enthusiasts, historians, and industry buffs. Maybe the dated materials stir memories, maybe they bring inspiration or provide context. Both Poor and Johnson see their work as honoring the industry’s first innovators and inventions so they won’t be forgotten.

“What if this gear could talk?” Poor said. “What stories would it tell?”