At Salomon headquarters in Annecy, France, designers and engineers have been working on a groundbreaking manufacturing process that could be game-changing in the world of custom gear.

In September, the design center’s doors will open to the public, so that anyone can use its new robotic unit to make a custom set of running shoes. Using these two robots and special software, a handful of specialists will help custom-build running footwear to any person’s feet.

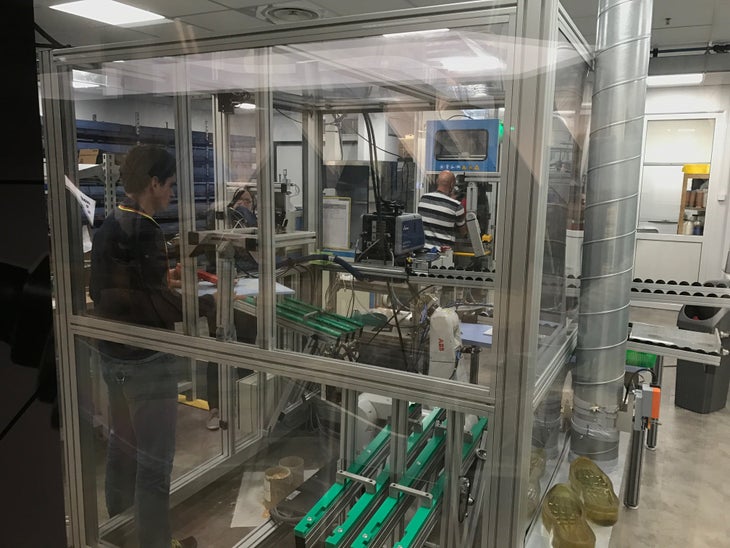

���ϳԹ��� Business Journal got a sneak peek at the process last month and saw the brand-new robotic units, called ME:sh labs, up close.

A Breakthrough in Custom Gear and Apparel

For years, brands have been offering customized gear. But it comes at a cost. Often, these products are made by hand, and customization is limited to color and aesthetics rather than fit. Salomon is trying to turn those limitations on their head, and build fully-customized shoes thanks to robots rather than manual labor.

The idea surfaced in 2008, when mountain athlete Kilian Jornet suggested that Salomon make customizable footwear available to anyone. At the time, the brand was also brainstorming solutions for the manufacturing industry, which was experiencing challenges with the rising cost of exchange rates and labor. A decade and millions of dollars later, Salomon may hold the keys to scaling customization in an efficient way.

How Salomon’s ME:sh Lab Robots Work

In a nutshell, here’s how the process works: first, a runner creates an online profile. She selects the cosmetics for her trail or road shoe and prioritizes features like breathability, cushioning, inserts, density, weight, and protection against debris. She schedules an appointment with the Annecy Design Center (ADC) ME:sh Lab (via the Salomon site), where her foot is measured using a 3D scanner, followed by a five-minute treadmill run to study foot strike technique.

After the data is collected—the runner’s intended usage, anatomical and biomechanical metrics, and subjective preferences (like toe box width)—the upper is created using a patented yarn with fusable properties, called Twinskin, which looks like a sock. The material is double-backed around a hard PU shell, and then the robot, called “Bea,” applies heat to meld the three layers. If a runner has foot injuries that require a softer shoe, she can choose to replace some sections of the PU shell with fabric.

The second robot, named “Maurice,” after its software, pre-applies glue for application of eyelets and other features by hand. Finally, the upper is manually assembled to the lower.

There are more than 531,000 possible combinations of materials and colors. ME:sh shoes can be designed in three days, and Salomon ensures a three-week turnaround on the whole process.

The ripple effect that individual manufacturing units could have on the traditional manufacturing model is considerable. This customization process, coined “Unique to Me,” sells for $300 a pair and eliminates the need for prototypes, because they’re all one-off models made to order. That helps cut down on materials waste, and reduces the carbon footprint of the manufacturing process, which would decrease material debris and the carbon footprint of those shipments.

When they’re made in the traditional way, running shoes involve an average of 50 components, and sometimes up to 100 people work on the design for a single pair of shoes. ME:sh footwear, though, is far simpler: each pair is made from 12 components, and only two people and two robots are needed for the process.

Salomon would not disclose the initial investment to get a ME:sh unit in a retail shop, but says it’s an expensive endeavor. Five or so retailers could buy a unit together, though, said Jean-Yves Couput, Salomon S/LAB Mesh project director. A unit would be profitable if at least 2,000 pairs of shoes are sold each year. That sounds like a tall order, but retailers also wouldn’t need to risk stocking inventory that might not sell.

“Labor costs are increasing and we need to find solutions,” Couput said. “In a decade, perhaps individuals will be creating shoes [with the ME:sh Lab] for a closed group—or, it will be possible to digitally print shoes and Salomon will be selling the machines and materials rather than footwear…we’re taking part in the risk [of innovation].”

In the next few months, prior to the ME:sh Lab launch, Salomon needs to select their software (which will display the data measured by the 3D scanning system), and finalize their technology for producing a digital last (imagine pin art that regains its shape after use), which would nix the need to either recycle the lasts or for the customer to buy her own. Couput also said he wants to improve the long-term strength of the Twinskin, so that its “stiffer, can survive more abrasion, and is suitable for the rockier higher terrace in Chamonix.” The valley’s higher altitude terrain is comparable to running the boulder or talus fields of a Colorado fourteener. (For context: I watched Jornet win the Mont-Blanc Marathon—which features rugged, rocky terrain—wearing his ME:sh pair, which is evidence to believe that the upper is durable.)

In the long run, the potential savings of time, materials, waste, and labor costs, enabled by custom, on-site manufacturing, could be significant, especially if the process is applicable beyond footwear.

“It’s possible to use this process for ski boots and bindings. We won’t do that anytime soon, but we know people will continue to ask for personalization, and everything can be customized,” Couput said, pointing out the increase of customization across the automotive and cosmetic industries.

Salomon plans to expand the availability of ME:sh units starting in China in early 2018, and then they’ll bring them to the U.S. In June, eight retailers in France and one in Belgium introduced models of Kilian Jornet’s ME:sh shoe—called the “Unique to Kilian”—as well as “Unique to Our Community” models ($230-$240), which are ME:sh shoes designed in partnership with retailers based on the needs of their community, which they keep in stock rather than customize for each person.

Review: How ME:sh Labs Shoes Perform

After I left the ADC ME:sh Lab, I visited a mobile shop in Chamonix to try a Unique to Our Community pair. These aren’t custom to me, but they’re targeted toward the needs of specific communities. The shop had four widths and gaiter options available. My feet are so narrow, though, that none of them fit. I needed a tighter fit, and the Kilian Jornet ME:sh pair worked best for me.

I tested them on a run on Chamonix’s valley floor, across rolling hills of compact dirt and steep sections of asphalt. I found that the shoe was exceptionally light, yet its upper was surprisingly stiff and secure. My toes felt protected, thanks to the PU melded beneath the mesh, and the tread and grip performed well on damp pavement.

They were comfortable right from the start, and I wanted to keep running. I’ve often had trouble finding the perfect fit for my hard-to-match feet, which are also two different sizes. I’d much rather skip the hassle of trying on pair after pair. For me, the comfort of a perfect fit could be worth the price tag of a fully customized pair.