Women’s gear is niche no more.

It’s hard to imagine a world in which women didn’t have access to outdoor gear that’s optimized for them. But that wasn’t always the case: ill-fitting apparel and hard goods were the norm for women as recently as 20 years ago, and even now, companies continue to make advances in women’s-specific product. To shine a well-deserved light on that innovation, we looked back at the watershed gear of the past—as well as today’s trend-setters—to name the top ten best women’s models (oldest to newest).

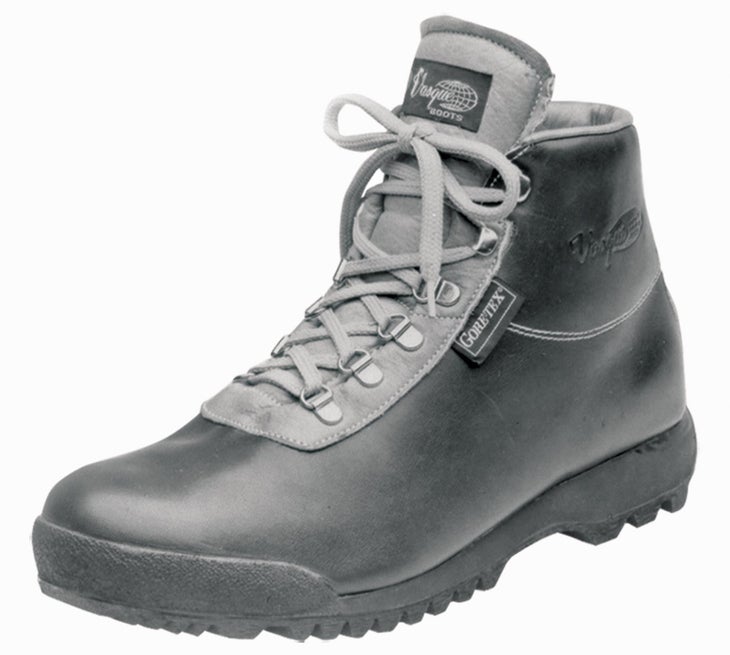

1. Vasque Sundowner hiking boot, 1984

“We’ve always had women’s product, from the very beginning,” said Brian Hall, director of product design for 52-year-old Vasque. Throughout the 1970s, well before the nascent outdoor industry started paying attention to women, Vasque’s catalogs included a full section of women’s footwear, and prominent photos depicted women hiking in the mountains. But it wasn’t until 1984, when the Sundowner hit market, that Vasque’s popularity among women skyrocketed.

“It was the first hiking boot to use cement (or glue) rather than welted stitching to attach the sole,” said Hall. That made the Sundowner lighter and easier to break in than those traditional heavyweights. And because it’s made of a single piece of leather (rather than many pieces seamed together), it conforms to the shape of the wearer’s foot. Thus, the Sundowner became a cult favorite among men and women.

But because Vasque offered the Sundowner in multiple widths, including a narrow last that fits many women very well, it earned special fame among women hikers.

“Our parent company, Redwing, has 3D foot scanners in shoe stores that have collected a huge amount of data for us over the years,” said Hall. Trends in that data allow Vasque to fine-tune the fit of both women’s and men’s models. That may explain why Vasque’s sales are split evenly, with women representing a full 50 percent of its buyers.

For fall 2015, Vasque re-launched the Sundowner using US-made leather. And for spring 2017, it’ll release a line of women’s trail-running shoes designed in collaboration with ultrarunners Gina Lucrezi and Krissy Moehl. “We’ve given ourselves a full two years of development and testing for this program,” said Hall. If past performance is any indicator of future success, Vasque could soon have another cult favorite in its lineup.

2. Dana Design Terraplane ArcFlex backpack, 1987

Grizzly-sized Dana Gleason might not look like a women’s pack designer. But like many women, he occupies a lesser-served portion of the sizing spectrum—and he knows firsthand how crucial fit is to a pack’s carrying comfort. In 1985, he founded Dana Design (which he sold to K2 Sports in 1996) to build high-performance packs for core users of all sizes, be they linebackers or Gleason’s 5’2” business partner, Renee Sippel-Baker. “She’d haul off and hit me in the kneecap if we didn’t cater to women,” Gleason joked.

Introduced in 1987, the Terraplane ArcFlex broke new ground by incorporating a polyethylene plastic framesheet. It was also the first backpack that could be customized for women: not only was it available in five different sizes (including small and extra-small) but it could also accept women’s-specific shoulder straps and hipbelt. These days, shoulder straps that sit closer together (to create a narrower neck opening) and angled hipbelts that accommodate a woman’s pelvis have become industry norms. But Dana Design was the first to offer such adaptations.

“The idea was to truly fit women with the same equipment we built for men,” said Gleason, who scorns at products that offer women little more than a flowery name and girly styling. “From a marketing perspective, [girly styling] might’ve been smart,” he conceded. “But we were building for hard-core users, which included women,”said Gleason.

Yes, some dealers were skeptical about carrying the full size range, and Gleason’s reps had to overcome assumptions that women’s didn’t—or couldn’t—carry big loads. But the sales figures soon ended any dispute: despite the $400 price tag—an extremely high bar for that era—the Terraplane’s various sizes and customizations proved very popular. “We sold huge numbers of packs to women,” said Gleason, adding, “This was not a token effort.”

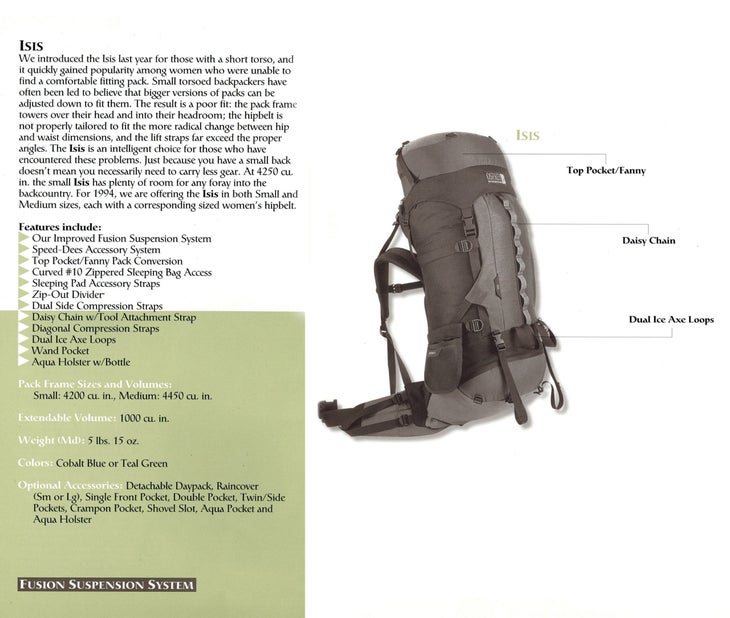

3. Osprey Isis backpack, 1993

When it debuted in 1993, the Osprey Isis became the first-ever women’s-specific pack. Whereas the Terraplane customized the packbag with a gal-friendly hip belts and shoulder straps, the Isis optimized the entire design specifically for the female physique. “It was an immediate hit,” recalled Osprey’s product line manager, Erik Hamerschlag. “We couldn’t build them fast enough,” he said. And the success was long-lived: for years, the Isis was Osprey’s volume leader, outselling every other model—even men’s models and smaller, less expensive packs.

Priced at $275 and offered in small (69L) and medium (73L) sizes, the Isis was the first pack to address not just women’s-specific fit, but also optimal load balance. Because women’s center of gravity tends to be lower than men’s, Osprey shifted the Isis’s volume accordingly, using a teardrop shape that placed most of the load-carrying capacity near the hips instead of at the shoulders. “Many packs available at that time could be adjusted small enough for women, but they towered over a short torso and exerted massive leverage, making it tricky to negotiate rough terrain,” said Hamerschlag.

Following up on the success of the Isis, in 1995 Osprey launched the Amelia, which cost $350 and offered a larger capacity (84L for size medium). The name pays tribute to Amelia Earhart (and the daughter of Osprey founder Mike Pfotenhauer). “The Amelia was also a strong seller from the get-go, and it was a rare option for women needing to carry a big load,” said Hamerschlag.

Reaching female customers proved fairly easy, thanks to Osprey’s emphasis on fit. “In those days, as now, we were selling a strong custom fit story, and women were an especially receptive audience,” Hamerschlag said. Osprey packs were micro-adjustable for torso length, and by bending the support stays, wearers could make the pack adapt to the unique curves of their back. “It was pretty labor intensive,” he said, “but back in those days, retailers were willing to spend the time to get it right.”

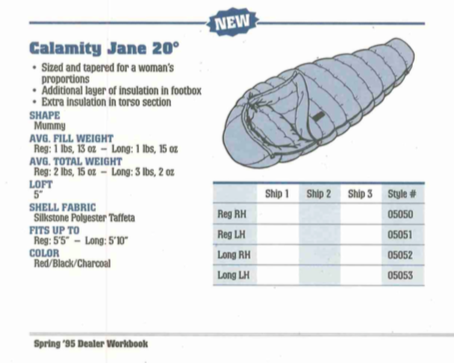

4. Sierra Designs Calamity Jane sleeping bag, 1995

In 1995, Sally McCoy had attempted Mt. Everest and served as vice president of product and marketing at The North Face. But when she became President of Sierra Designs in 1994, she made sure to include women’s gear among the company’s various innovations. “Women, who made less money than men (still true), had to pay more and carry more weight to be warm at an equivalent temperature,” said McCoy. Her solution: the Calamity Jane, the industry’s first women’s-specific sleeping bag, which debuted in spring 1995—and sold 18,000 units in its first year.

“Conventional wisdom and scientific evidence indicate that women sleep colder, as well as have different average sizes and shapes, than men,” the workbook read. “In spite of this, women have had to make do with sleeping bags built and engineered for men.” So the 20°F Calamity Jane ($150) and its cold-weather sibling, the 0°F Annie Oakley ($195), offered several features aimed especially at women: the cut was narrower at the shoulders but wider at the hip, the Thinsulate Lite Loft Insulation was beefed up through the core and footbox, and the bags came in shorter lengths (5’5” and 5’10”). Women snapped them up.

“Although initially retailers looked with raised eyebrows at SD’s gamble to introduce women-specific sleeping bags to the market, they are not looking askance at the concept anymore,” wrote Michael Hogson in his 1995 product review for The Spokesman-Review. “Women are lining up to buy the bags and for good reason: They work!”

The sales success of the Calamity Jane proved to Sierra Designs and the entire outdoor industry that there was a strong demand for women’s product. “It broke a ceiling, it really did,” said Melodie Miller, who worked as a product designer for Sierra Designs (before and after McCoy’s time there) as well as REI and Gaiam, where she currently serves as director of global sourcing and product development. “It ignited a fire in everybody, and opened the door for everything we find today.”

Suddenly, women’s gear didn’t seem niche: it seemed like a huge sales opportunity, one that outdoor companies would be foolish to ignore.

5. Isis Niobe jacket, 1999

“It seems so odd now, but [in the early 90s], there really weren’t women’s-specific products,” said Carolyn Cooke, who (with Poppy Gall) co-founded the women’s outdoor apparel brand Isis in 1998. “We fit who you are,” read the company’s tagline. The Niobe down jacket was among the first products Isis offered in its debut collection for Fall 1999, and it became one of the company’s perennial bestsellers.

“Back then, a lot of the outerwear was unisex,” Cooke said. By the mid-90s, a handful of brands such as Marmot, Mountain Hardwear, and L.L. Bean started offering rainwear in women’s sizes (and in 1995, Marmot expanded its Alpinist outerwear collection to include women’s models). Gals’ jackets came with shorter sleeves, shorter torso lengths, smaller neck openings, and a wider flare from waist to hip; pants featured wider hips and thighs, and a higher back rise.

But the down jackets were still Michelin-Man bulky, Cooke recalled. The Niobe broke that mold by shaping the baffles for a more flattering fit. It also distinguished itself with colorful, patterned linings and zipper tape. “The market response was really great,” Cooke said. The Niobe and the success of Isis overall proved to the industry that women represented a valuable market. The brand lost momentum after its sale to American Recreation Products, which eventually sold it. “Brand is more than products,” Cooke said. “At the end of the day, it’s about connecting with your customers and knowing who they are. We were truly focused on women, made by women.”

6. Oboz Mystic Low BDry Hiker, 2011

Knowing what women want is notoriously difficult to divine, and building a “women’s” shoe is also fraught with contradictions. But Josh Fairchilds, who co-founded Oboz in 2007, suspected there were trends that differentiated a woman’s foot from most men’s, and research confirmed his guess: a 2001 study on gender differences in foot shape published in Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise gave him plenty of insights upon which to build a women’s-specific hiking shoe.

In 2011, Oboz launched the Mystic ($125 for the low-cut version) which puts the shoe’s flex point further forward, in response to data indicating that women’s toes tend to be shorter in relation to their overall foot length. “If the flex is too far back, the shoe will bind across the top of her foot,” explained Fairchilds. The Mystic’s low volume also corresponds to data suggesting that women’s feet tend to have less overall girth.

“It should fit most women better, but it won’t fit all women,” said Fairchilds. Still, the Mystic’s sales have steadily increased since its release, so that Oboz plans to refresh the line for Spring ’17 with four new women’s models, all built on the proprietary Mystic last. “There are measurable differences between men’s and women’s bodies,” said Fairchilds, “and we can enable a product to perform better if we address those anatomical differences.”

7. Columbia Back Beauty Pant, 2011

With the rising popularity of stand-up paddleboarding, Columbia Sportswear started hearing from its female watersports athletes that plumber’s crack was becoming a ubiquitous problem. Bending forward while wearing ill-fitting pants (or pants that slackened when wet) was exposing more than paddlers cared to reveal. So in summer 2011, Columbia debuted the women’s Back Up Hydra Short, which used a neoprene waistband and a novel, dual-yoke design that didn’t droop during extreme maneuvers. “But we knew the feature would have broader appeal than just watersports,” said Stephanie Thurber, product line manager for Women’s Performance Sportswear. In Fall 2011, Columbia introduced the Back Beauty pants, now offered in Boot Cut Pant, Long Sport Short, Skinny Pant, Capri, Straight Leg Pant, and Boot Cut in Plus Size.

Marketing the Back Beauty required some delicacy: the goal was to let women know that even during sport, the pants hid their lumps and kept cracks covered—but Columbia couldn’t exactly say so explicitly. Instead, hang tags and point-of-sale signage advertised the pants’ ability to prevent crack-exposing gaps at waistline. Women bought in, in a big way.

“They’re our best-selling women’s bottoms,” said Michelle Aubrey, general merchandising manager for sportswear. Because of that popularity, the Back Up waist design was also integrated into the company’s other hiking and travel pants.

Part of the appeal is fit and coverage. But the Back Beauty pants also give active women a non-baggy athletic option. “That was an a-ha moment for us,” said Thurber. “Women didn’t want baggy shirts and pants,” she explained. “So our challenge has been to use materials and construction that allows for free movement but looks form-fitting and flattering.”

8. Trew Chariot Bib, 2012

Introduced in Fall 12, the women’s Chariot ski bib ($399) offered women a convenient way to answer nature’s call. The design uses two side zips that extend from the knees to the armpits. To perform a “bio-break,” you simply unzip one of them and pull the pants fabric to the other side. “We came up with it because it made easier for us [men] to do #2,” explained Trew co-founder and product designer Chris Pew. But core female skiers such as Shaun Raskin embraced it as a brilliant innovation for women.

Ladies’ technical outerwear has traditionally used a zippered crotch or a rainbow-style drop seat to facilitate bathroom breaks. Patagonia continues that tradition in Fall ’16 with an insulated pant and three-layer hardshell, both with crotch zippers. But such designs either require compatible, open-crotched base layers–or a lot of fussing to move tights away from the open drop seat.

Now dubbed the “she-pee,” Trew’s side zip makes it easy to manipulate undergarments and get all clothing out of the line of fire. But it’s not intuitive: Trew has had to circulate how-to videos via Snapchat and blog that educate potential and current Chariot owners about the zippers’ functionality.

Still, the Chariot has been well received among dedicated end users, and may have had even greater impact on the market than the men’s version, said Pew. “When women find our bibs, they’re thrilled,” he says. “A lot of brands aren’t catering to those women, so they thank us for it.”

9. Orvis Women’s Silver Sonic Convertible-Top Waders, 2013

Before spring 2013, Orvis made quality women’s waders, but kept hearing complaints about the fit. So the company spent a year working with fit models that represented a wide range of women’s shapes to produce the Silver Sonic Convertible-Top Waders ($279). They come in 14 sizes (and three lengths), and women rave about them: the 95 product reviews on Orvis’s web site average 4.8 stars out of five—and all but one reviewer would recommend them to others.

Not only did the initiative draw on lots of fit models, but it also involved the female anglers on Orvis’s staff (such as product developer Molly Urquhart). “They know that user group best,” said marketing manager Tom Rosenbauer. “When we design a new rod we talk to guides and similar influencers, and when we designed our women’s waders, we talked to women.”

Knowing what women want—flattering fit integrated with top performance—proved easier than building it. Men’s waders enjoy straightforward sizing: chest, waist, and hip can all be roughly the same measurement, so the bib is easy to construct. But women’s measurements vary widely, and simply making baggy waders doesn’t effectively solve the problem: not only is that extra bulk unflattering, it’s abrasion-prone. “Durability is better when a wader is fitted, because all those bags and sags rub together and form hot spots that eventually become leaks,” said Rosenbauer.

Thus the women’s Silver Sonic uses a relatively fitted cut in all sizes (and even in the bootie, which have historically been sized too large for women anglers). Smart seaming, rather than baggy proportions, delivers full freedom of movement. And Orvis’s proprietary SonicSeam welding on four-layer fabric makes them as performance-oriented as the company’s top men’s options. Thus, the Silver Sonic has enjoyed strong sales without the boost of special marketing initiatives.

“There aren’t too many fly-fishing products that vary by gender,” said Rosenbauer. Men and women use the same rods, lines, reels, and leaders, so “We talk to women and men the same way, speaking from our common passion for fly-fishing,” he said. “But, you do need waders that fit.”

10. Knixwear Evolution Bra, 2015

Until the Jogbra debuted in 1977—when a frustrated runner invented what she believed would be a “jockstrap for women”—women had no sports bras, only underwires and fashionable pieces of lingerie that didn’t pass muster during active endeavors. Since then, the sports bra and lingerie categories have remained relatively separate, until Joanna Griffiths introduced the Evolution Bra ($55) last year.

“I thought, how cool would it be to have a non-underwire bra that an active woman could wear throughout her day,” said Griffith, who sees the Evolution as supportive enough for hiking and yoga, flattering enough for work and nightlife, and comfortable enough to wear for hours.

“It’s not a straightjacket running bra, but it uses quick-dry, anti-odor, moisture-wicking fabric that outdoor users have come to expect,” she said. All eight sizes are optimized for that user—Knixwear developed the bra with 70 wear-testers in varying sizes—and the seamless construction reduces chafing. The option of switching between cross-back and straight straps lets the bra adapt to a woman’s outfit and her need for support (the cross-back is more breast-stabilizing than straight straps). That gives it the versatility to handle everything from backcountry skiing to presentations at the office.

“It’s the first bra I’ve met that hits all my key boxes: it’s light, packable, and quick-drying enough for me to want throw it in my pack for any trip,” said Backpacker senior content editor Rachel Zurer. “Unlike the other sports bras I like, I don’t have to pick between something that looks good under a shirt at work or something that really performs when I’m sweating.” That makes the Evolution a true quiver-of-one.

It also illustrates the continuing evolution of women’s gear. Having access to pretty good sports bras isn’t where the story ends for active gals, or for product innovators. Women want gear that’s optimized for them—and these days, they’re getting it. Though meeting that goal will keep designers busy through the coming decade and beyond.