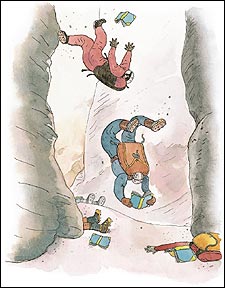

OVER THE LAST TWO DECADES, Michael Kelsey’s quirky guidebooks have been fixtures at trailheads all over the Four Corners region, inspiring people to explore the sunburned lands beyond our national parks. But environmentalists and backcountry managers claim that Kelsey’s popularizing has led to overcrowding, resource damage, lost hikers, and injuries. Given all that, it’s a safe bet they’ll pan his 16th book, a 300-pager called Technical Slot Canyon Guide to the Colorado Plateau. Due out this spring, it’s the first major manual on technical canyoneering, a fast-growing sport that involves rappelling into and traveling through remote, flood-prone slot canyons: narrow gullies that are difficult or impossible to exit during an emergency.

ONLINE FORUM

Is the booming sport of canyoneering getting out of control? Join the discussion.

“Canyoneering is not for everyone,” says Adele Smith, 48, a former field instructor at the National Outdoor Leadership School and 25-year veteran of Utah’s canyons. “A guidebook on something that technical is just incomprehensible.”

Not so, responds Kelsey, who rejects the notion that his books will spoil the canyoneering party. “I’m giving people the opportunity to have a little adventure in life,” he says. “I don’t know what the hell the controversy is.”

The problem, say critics, is that Kelsey’s self-published guides—each as idiosyncratic as its author, an intense 60-year-old loner from Provo, Utah, with a master’s degree in geography and a fondness for speed hiking in cast-off running shoes—send too many newbies into unspoiled, potentially dangerous territory. They also contend that Kelsey’s estimated route times are unrealistic, setting amateurs up for trouble. Officials at Utah’s Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument will no longer sell Kelsey’s books. His enthusiastic write-up on the Black Box has helped popularize the route; some 70 search-and-rescues have taken place in the past two decades.

“Michael Kelsey makes things look easy,” says Barbara Sharrow, assistant manager for visitors at Escalante. “We find that his books mislead the public.”

At least one early reviewer of the Slot Canyon Guide sees potential potholes. Steve Brezovec, 30, a canyoneer who read a draft of the book for Kelsey, was shocked that it included a little-known Escalante slot that’s regularly choked with impassable 20-foot logjams. If a group enters it in the wrong conditions, Brezovec says, “they’ll probably die.”

Others think Kelsey catches too much flak. “Michael, unfortunately, has become a scapegoat,” says Rich Carlson, 46, president of the American Canyoneering Association, which promotes canyoneering safety and ethics. The sport’s real problem, he says, is its rapid growth: “Beta is spreading faster than knowledge about safety.” In places like Zion National Park, he points out, popular routes such as Behunin Canyon have seen a 1,200 percent increase in use over the past five years.

Kelsey, meanwhile, is already looking ahead. “There’s a million other canyons out there,” he likes to say. This month he’ll slip down several as he works on his book’s expanded second edition.