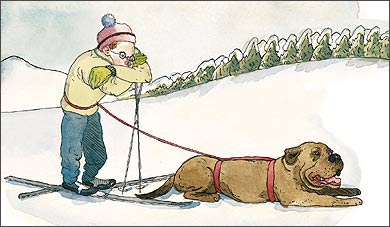

As a teenage Jack London fan, I fantasized about mushing a dogsled. Grown-up city life derailed my Iditarod dreams until I came across a photograph of someone skijoring: two large, smiling malamutes towing a cross-country skier down a forested trail at breakneck speed. It appeared I could live out my fantasy with a pair of skis, a rope, and a harness.

DETAILS

The Cascade Skijoring Alliance () holds runs and events at Mount Hood and other locations in central Oregon.

So I called Dina McClure, founder of the Cascade Skijoring Alliance, in Bend, Oregon, and asked her to teach me.

“Sure,” she said. “What kind of dog will you be working with?”

Ella, my co-worker’s 50-pound mutt, was sleeping upside down behind my desk, her legs immodestly splayed. She’s two years old, doesn’t retrieve sticks, rarely comes when called, and has never seen snow.

“I’ll be bringing Ella.”

“And what breed is Ella?”

“Well,” I said, “she’s brown.”

Ella and I meet McClure at the Ray Benson Snow Park, off U.S. 20 on Santiam Pass in Oregon’s Willamette National Forest. Rosy-cheeked and 44 years old, McClure switched from dogsledding to “ski driving” seven years ago after she retired some dogs and decided two canines would be easier to keep than a dozen. She’s seen her club expand to 70 members.

After fitting the harness, McClure instructs me to run Ella a few hundred yards through the snow, keeping some tension on the line. No problem. Next, McClure clips a trailer tire to Ella’s harness with the idea that I’ll run ahead of her and she’ll drag the tire. The exercise immediately goes awry—Ella freaks out and bolts, surmising that the tire is actually chasing her.

We give Ella a break so McClure can show me the sport for real. Her Alaskan huskies, Bailey and Tyler, look nothing like the pooches in the picture I saw. Like coyotes, they’re fairly small, with rough coats, reddish eyes, and narrow snouts. They remind me of the type of beast that might chase me through the frozen woods until I collapse and beg for death to come.

McClure explains that larger dogs, like the happy malamutes, are best for pulling heavy loads; smaller dogs excel in four- to seven-mile races. Attached to her dogs by a waist harness and an eight-foot towrope connected to a bungee cord, McClure hunkers down to lower her wind resistance and center of gravity, calls out “Let’s go!” and takes off with the acceleration of a water-skier behind a jet boat. Ella barks excitedly at the sight.

Next, for the full-blown try, McClure clips me to Ella, skis 50 yards ahead on the groomed trail, and calls to my furry steed. Perhaps accessing a genetic memory of the task, Ella bounds toward McClure—stretching the bungee line with remarkable force. I push with my poles and we’re off, Ella pulling me along at a jogger’s clip. I would like to tell you that the moment fulfills my fantasy: speeding through winter landscape, a man and his dog. But the truth is, I’m focusing all my concentration on staying upright. I nearly run over my teacher while trying to stop.

“She could be a great skijoring dog,” says McClure, genuinely impressed with Ella.

My partner jumps around, seeming to understand that she is the teacher’s pet. I’m on my knees in the snow trying to catch my breath. After giving Ella a treat, McClure turns to me with one final instruction: “You,” she points out, “could use some cross-country skiing practice.”