INSIDE ONE OF THE UBIQUITOUS GO-GO-BARS that line Soi Diamond Alley, in Pattaya, a seaside town 90 miles south of Bangkok, a handful of balding, potbellied foreigners are drooling over a dozen Thai girls strutting along the bar to the blare of disco music.

wildlife conservation, endangered species, poaching, poachers, environmental law, wildaid

Galster tracks aloe-wood poachers with one of WildAid’s rangers in Khao Yai National Park.

Galster tracks aloe-wood poachers with one of WildAid’s rangers in Khao Yai National Park.wildlife conservation, endangered species, poaching, poachers, environmental law, wildaid

Steve Galster, WildAid's co-founder and point man in Thailand, meets with one of his informants, a former go-go girl based in Pattaya, a hub of black-market activity.

Steve Galster, WildAid's co-founder and point man in Thailand, meets with one of his informants, a former go-go girl based in Pattaya, a hub of black-market activity.wildlife conservation, endangered species, poaching, poachers, environmental law, wildaid

Cold-irons-bound: Thai authorities frequently confiscate Asian black bears during animal-trafficking raids; WildAid field director Tim Redford designed these holding pens at the Banglamung Wildlife Center, outside Pattaya. “We know there are illegal restaurants where you can eat bear meat,” says Galster, pictured here.

Cold-irons-bound: Thai authorities frequently confiscate Asian black bears during animal-trafficking raids; WildAid field director Tim Redford designed these holding pens at the Banglamung Wildlife Center, outside Pattaya. “We know there are illegal restaurants where you can eat bear meat,” says Galster, pictured here.wildlife conservation, endangered species, poaching, poachers, environmental law, wildaid

Where the wild things aren't: The Sriracha Tiger Zoo, near Pattaya, is an infamous tourist attraction where protected tigers and crocodiles are put on display. The zoo was busted by the Thai police in fall 2003.

Where the wild things aren't: The Sriracha Tiger Zoo, near Pattaya, is an infamous tourist attraction where protected tigers and crocodiles are put on display. The zoo was busted by the Thai police in fall 2003.wildlife conservation, endangered species, poaching, poachers, environmental law, wildaid

Tiger tales: Galster giving a talk at the Southeast Asia Environmental Law Enforcement Training Center, which WildAid established at Thailand’s Khao Yai park to teach rangers how to use counterinsurgency tactics against poachers

Tiger tales: Galster giving a talk at the Southeast Asia Environmental Law Enforcement Training Center, which WildAid established at Thailand’s Khao Yai park to teach rangers how to use counterinsurgency tactics against poachers

Sitting at a nearby table, under a revolving mirror ball, Steve Galster seems immune to such louche diversions. A clean-cut, six-foot-five native of Green Lake, Wisconsin, he looks like a generic American, dressed in standard-issue blue jeans and a long-sleeved oxford shirt. While the men around him pant, he chews his bubble gum, orders a beer, and waits.

A few minutes later, a young woman in a cleavage-baring black T-shirt walks up and kisses Galster on the cheek. A former go-go dancer who now works as his paid informant, she pulls a small Ziploc bag from her purse and slides it across the table. The bag contains aloe wood—an aromatic essence so highly valued that some Asian poachers have killed to obtain it. It’s illegal to sell native aloe wood in Thailand, but the stuff is routinely smuggled out of the country anyway, because Middle Eastern consumers prize it as incense. The wood can wholesale for $1,000 per kilo.

Galster slowly opens the baggie and nods.

“The main aloe trader in Pattaya is from Iraq,” the woman says. “He keeps some wood in his store, but there’s no problem if you want more. The guy says he has a warehouse full of it.”

That’s all Galster needs to hear. He heads out the door and into Sin City—alleyways crowded with stores offering bootleg Viagra, cheap plastic surgery, and cheaper sex, not to mention crocodile purses with beady-eyed heads still attached, illegal pelts from endangered animals, and aphrodisiacs like tiger-penis wine. Despite his subdued midwestern manner, the 42-year-old Galster seems energized, clearly reveling in the hunt.

Before long he finds the small shop he’s after. The window display includes a glass case full of fake Rolex watches and another stocked with aloe-wood oils in ornamental bottles. Galster walks up to the owner, a middle-aged Iraqi with a clipped rectangular mustache, and explains that he wants to export aloe wood to the United States. This sounds unlikely coming from a farang—the Thai term for a foreigner—but the trader doesn’t hesitate. He pulls out a large white plastic box filled with wood chunks. Then he breaks off a tiny piece, drops it in a small metal urn, and lights it, dispersing the fragrant smoke with circular waves of his hand.

Galster inhales. “That’s good,” he says conspiratorially. “Like hashish.”

“Good?” says the dealer. “It’s the best! This little bag costs $2,500—more expensive than gold. There are only limited quantities left, and it is hard to get.”

“Limited quantities” is one way of putting it. Even though it’s against the law to remove aloe from national parks in Thailand and Malaysia—practically the only places where the wood can still be found in either country—poachers are busy chopping down trees. Traffic, a UK-based group that monitors worldwide trade in protected plant and animal species, warns that aloe wood may soon become commercially extinct due to overharvesting.

Galster lays down enough cash for a 12-gram baggie and leaves. ���ϳԹ���, he checks to see if the palm-size digital video camera he’s been using is still recording. Then Galster—a man whom many wildlife experts consider the planet’s most effective sleuth in the shadowy world of endangered-species smuggling—starts speculating about what he’s just seen.

“I feel bad suspecting that guy, because he may just be an Iraqi shopkeeper trying to make a little money,” he says. “But we saw the watches and the wood. They’re both illegal businesses. And people in piracy often fund other illegal activities.”

What Galster is suggesting is that this small-time crook may be tied into something bigger—namely, a black-market financial network that funds terrorism. “I just can’t help wondering whether Iraqi aloe-wood dealers are raising money for something else, like Al Qaeda,” he adds. “We’ll have to keep looking into it.”

That sounds like gonzo conspiracy theory—and, in fact, no connection between plant or animal trafficking and terrorism has been established—but it may not be too far-fetched. Two years ago, in a much-publicized story that broke half a world away from Galster’s Asian beat, a gang of cigarette smugglers based in Charlotte, North Carolina, pleaded guilty to skimming $1.5 million and funneling a portion of it to Hezbollah, the Lebanon-based Islamic terrorist group. William Wechsler, an expert on the financing of terrorism at the Council on Foreign Relations, in New York, points out that “local terrorist cells are supposed to support themselves, and they do that by committing everything from penny-ante financial crimes to credit card fraud. So animal trafficking, as an easy source of quick and illegal money, would not be unusual for terrorists to take advantage of.”

Galster has spent the past two decades working as a political and environmental detective, often under cover, and during that time he has specialized in collating intelligence on the global flow of contraband—be it grenades, ganja, girls, or gorillas. Along the way he’s made some unusual connections. He spent part of the late eighties embedded with the anti-Soviet mujahedeen in Afghanistan, where he watched the guerrillas routinely use opium profits to buy weapons. In the nineties, while helping Russian police and environmental officials break up a ring that was smuggling the pelts (and parts) of endangered Siberian tigers, he saw firsthand that the crooks were also involved in an entirely different enterprise—moving women into the sex-slavery trade in Japan.

Whether Galster is right or wrong about his Iraqi merchant, his investigative skills have definitely advanced the cause of animal protection. In recent years he’s focused his energy on helping create and lead an innovative new group called WildAid, a lean, aggressive conservation outfit that’s taking direct action against poachers and traffickers in species-rich but economically poor countries like Thailand, Cambodia, Ecuador, and Russia.

WildAid’s mission is straightforward: training local law enforcement and wildlife officials to fight poachers, in an attempt to protect national parks, wildlife preserves, and other places that represent the last stand for many endangered species. Because modern wildlife crime is becoming increasingly complex, Galster believes the tried-and-true approach that conservation groups have followed for decades—raising money, funding scientific research, and using a worldwide bully pulpit to campaign against species destruction—is both passive and passé. He’s convinced that only a strong, proactive approach to animal security can save species that are on the brink of extinction.

Given all this criminal activity, is it possible that Galster sometimes gets carried away imagining how the various bad guys might fit together? Maybe. But he’s paid to think outside the box, and there’s no denying that he’s accomplished a lot by following up on his wildest ideas.

ACCORDING TO A 2001 REPORT issued by the United Nations Environment Program, the illegal global wildlife trade is a $5-billion-a-year industry. So it’s no wonder such exotic species as the clouded leopard and the Malayan sun bear—whose skins and gall bladders, respectively, can sell for $1,000 apiece—are being hunted to the vanishing point in their last remaining habitats: the national parks that Galster calls the “Fort Knoxes” of the animal world.

Unfortunately, the forts keep getting plundered. Some 900 of the earth’s plants and animals are considered so close to extinction that their sale is prohibited by the Geneva-based Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES), a UN treaty organization that regulates the world’s legal wildlife traffic. Another 24,600 species are threatened to such a degree that CITES controls their trade through quotas. That doesn’t help the 762 plant and animal species that, according to the Red List, a survey of threatened species compiled in 2003 by the World Conservation Union in Switzerland, have been wiped out over the past 500 years. As Edward O. Wilson noted in his 1999 book The Diversity of Life, “The sixth great extinction spasm of geological time is upon us, grace of mankind. Earth has at last acquired a force that can break the crucible of biodiversity.”

WildAid was founded in 1999 to turn back this tide. It’s the brainchild of Galster and three colleagues: Suwanna Gauntlett, 40, who previously ran the Gauntlett Group Inc., an eco-consulting firm that helped industrial giants such as Nike and Alcoa make their factories run cleaner; and Peter K. Knights and Steven Trent, two 40-year-old trafficking experts from Great Britain who previously worked for the London-based Environmental Investigation Agency (EIA), a nonprofit that specializes in exposing environmental crime. WildAid has three broad aims: hunting down and stopping poachers; exposing and eliminating black-market trafficking operations; and using public-awareness campaigns to stop the human consumption of exotic plants and animals.

The group received its initial seed money—$1 million—from the Barbara Delano Foundation, a San Francisco–based green fund created by the late Barbara Delano Gauntlett, Suwanna’s mother and the heir to the Upjohn Pharmaceutical fortune. These days, the foundation provides 38 percent of WildAid’s $5 million annual budget; the rest comes from institutional grants and public donations, 100 percent of which go directly into international field projects, which will cost about $4 million this year.

A significant part of WildAid’s appeal to donors is its fast-and-light approach. The group operates out of small offices in Phnom Penh (where Gauntlett is based), London (Trent), San Francisco (Knights), and Bangkok (Galster). While larger groups such as the World Wildlife Fund (with an annual budget of around $300 million) continue to rely mainly on a scientific approach—studying animal populations, monitoring species, and relaying the results to the public—WildAid attacks poaching and trafficking hot spots with 48 staffers who are not primarily biologists but activists, undercover investigators, economists, and law enforcement officers. Each office is manned by a mix of locals (like Krisana Kaewplang, 32, who speaks Khmer and specializes in community outreach and ranger training in Thailand) and globe-trotting professional activists (like Tim Redford, a 43-year-old Brit who built endangered-animal sanctuaries for the Thais before joining WildAid).

“Rather than spending a lot of money on U.S. infrastructure and holding workshop after workshop, we believe in direct spending in the field,” says Gauntlett. “There are 30,000 parks in the world, most of which are not protected at all. That’s why we dedicate ourselves to direct protection of wildlife preserves in developing countries, which have the will to fight animal crime but not the funds or the expertise.”

WildAid has put this theory into practice in Thailand, setting up the Southeast Asia Environmental Law Enforcement Training Center, in Khao Yai, an 867-square-mile national park that’s home to endangered Asian elephants and sambar deer; in Cambodia, where the 560 square miles of Bokor National Park are now patrolled by WildAid-trained rangers who carry AK-47s; in Russia’s Far East, where anti-poaching teams are fighting to save Amur tigers and leopards; and in Ecuador’s Galápagos Marine Reserve, where they built two new ranger bases to help expand protection of the islands and surrounding waters. Last year, when the actress Angelina Jolie volunteered to put up $1.5 million for the protection of a 240-square-mile Cambodian forest that was overrun with freelance gold miners and marauding game hunters, she turned to WildAid for help. Gauntlett helped assemble a 50-man force made up of former Khmer Rouge soldiers for what became known as the Maddox Jolie Project, named after Jolie’s adopted Cambodian son. Galster calls them “Jolie’s Rangers.”

In the four years that WildAid has operated in Cambodia, the group has helped confiscate 17,300 live animals, two tons of body parts, and two tons of bushmeat. In Thailand, they’ve helped the government rescue more than 35,000 live animals just in the last nine months—from six tigers caged in a private home to 1,000 crocodiles in a private zoo—and park rangers in Khao Yai have confiscated some five tons of aloe wood. In the Galápagos, WildAid has trained rangers to halt illegal turtle poaching and stop fishermen who supply shark fins to Asian markets, where an environmentally destructive delicacy called shark-fin soup is a prized dish.

Methods like these have put the conservation world on alert that there’s a cutting-edge group out there with a revolutionary new approach. “I’m an ecologist, and we freely think we can tackle any problem,” says John Seidensticker, chairman of the Save the Tiger Fund Council and a senior scientist at the Smithsonian National Zoo, in Washington, D.C. “But sometimes we ecologists should just sit back and listen to the people who know about security. As far as I’m concerned, Steve Galster is the best conservation-security expert operating in Asia today.”

BORN IN 1961, GALSTER FIFTH of seven children. He grew up mostly in Wisconsin and Michigan, where his father ran a landscaping business. When he was a kid, he liked to round up roadkill and give the animals proper burials in his own pet cemetery. This led to his first foray into political activism: a letter sent to then–first lady Pat Nixon in the early seventies, urging her to erect fences along the entire U.S. highway system to keep animals from wandering into traffic.

Back then, Galster figured he would grow up to be a high school biology teacher or a veterinarian, but he ended up majoring in political science at Grinnell College, in Iowa. In 1986, he enrolled in a security studies graduate program at George Washington University, in Washington, D.C., where most of his teachers were either employees or alums of the Central Intelligence Agency, the Pentagon, the National Security Agency, the State Department, or the White House. It was there—and during a subsequent job at the National Security Archive, a GWU think tank that oversees the world’s largest collection of declassified U.S. government documents—that he learned to “treat every little piece of intelligence as significant information, part of a puzzle that becomes clear only later, when you put all the pieces together.”

Galster coupled his curiosity with an inherent affinity for intrigue. In 1988, the Archive assigned him to analyze the U.S.-Soviet proxy war in Afghanistan, starting with declassified documents in which important information had been blacked out. He filled in the blanks by traveling to Moscow and convincing a few Soviet academics to endorse a visit to Afghanistan. He started off embedded with Soviet troops but ended up hanging out with the CIA-backed mujahedeen.

“The Russians were just desperate for people to tell their side to,” Galster remembers. “When I got to Afghanistan, I met an Islamic fundamentalist commander—Gulbuddin Hekmatyar, who was getting a lot of the U.S. money and guns—and I became convinced he was the wrong guy for us to back. I made it a point to tell that to the other mujahedeen, who hated Hekmatyar, and that opened the door to them inviting me to check out their operations.”

He recounts all of this blithely, but the work was both dangerous and enterprising. “I think Steve was fortunate that he began his Afghan project when glasnost was starting and the Kremlin had decided that they had a certain story to tell,” recalls Thomas S. Blanton, director of the Archive. “That the Soviets chose to tell it to him showed he understood that if you go straight to the primary sources, you can quickly become an expert while all the cud-chewers back home are still passively looking into it. He did a remarkable job.”

In 1991, the EIA hired Galster and his girlfriend at the time, an Africa scholar named Kathi Austin, to examine the connections between civil wars in Africa and the ivory trade. They got started by joining a Young Republicans chapter in Washington, which led to their meeting what Galster calls “mercenaries and right-wingers” who were supporters of such rebel leaders as Jonas Savimbi, in Angola, and Alfonso Dhlakama, in Mozambique. Posing as conservative journalists, the pair traveled all over southern Africa and met members of the Mozambique National Resistance (a.k.a. Renamo), who were arming themselves by selling elephant ivory, rhino horns, and gems. After more than a year of research, their 1992 report for the EIA, “Under Fire: Elephants in the Front Line,” helped convince CITES to uphold the international ban on the ivory trade.

Galster was hooked. In 1993, working for the EIA, he dove back into the international rhino-horn trade, this time posing as a wealthy South African buyer and tracing one ring from South Africa to Asia. After convincing a major trafficker—who was moving rhino horns with the aid of Chinese government officials—that his financial interest was sincere, Galster was personally escorted to a 1.2-metric-ton hoard, housed in a huge warehouse on a remote stretch of the China-Vietnam border. Using a hidden camera, he captured footage of more than 500 rhino horns.

Back in Washington, the EIA arranged to show Galster’s video to a contact at the National Security Council, the president’s principal foreign-policy advisory group. At the time, the U.S. was threatening trade sanctions against the Chinese for not enforcing their own laws against the rhino-horn and tiger trade. With the help of the NSC, the EIA showed the video to delegates at a CITES meeting in Brussels that September. The Chinese government was caught flat-footed, and responded by raiding the warehouse, seizing the contraband, and holding a publicly televised rhino-horn bonfire in October 1993. Not long after, it banned the sale of rhino horns in China altogether.

For Galster, it was a spectacular success, and though he plays down the risks, they were real. “One lonely American in the middle of nowhere?” says Ted Osius, a State Department Asia expert who has helped secure federal funding for WildAid’s Southeast Asia Environmental Law Enforcement Training Center. “Man, if the rhino-horn dealers were willing to eradicate an entire species, they definitely would have popped him if they’d found out what he was doing. He’s got guts. He was definitely risking his life.”

Still, Galster felt that he wasn’t even scratching the surface of animal trafficking, which is why he decided to join forces with Gauntlett, Knights, and Trent. By 1999, they were all running up against frustrating limits in their particular fields. Galster, who first met Gauntlett when he requested emergency funding from the Barbara Delano Foundation to combat tiger poaching in Russia, was finding it difficult to raise money for his own anti-trafficking operation, the Global Survival Network. Gauntlett was itching to get her hands dirty fighting poachers in the field. Knights, who by then was managing the Delano Foundation, missed the conservation-security work he’d been doing for the EIA. And Trent wanted to make a longer-term impact on environmental crime.

“We all had the same thought,” Galster recalls. “That other organizations with lots of funding were getting nowhere against trafficking—but maybe we could get somewhere, with less money, spent on field programs directly overseen by us.

“It was one thing to uncover an illegal trade, point fingers at corrupt players, and then have nothing happen. It was another to be able to follow up undercover research with action.”

GALSTER FIRST CAME UP WITH the prototype for WildAid’s current programs in 1993, on an excursion to Vladivostok to help disrupt a Siberian-tiger-trafficking ring.

When he arrived in the Russian Far East on behalf of the Tiger Trust, a nongovernmental organization based in New Delhi that protects tigers in India, it was, he says, “virtually open season on wildlife.” Biologists estimated that there were no more than 250 Siberian tigers left in the wild; dozens were being killed each year by poachers who hunted on foot, by car, and by helicopter. Galster assembled and trained three five-man patrols made up of Afghan-war veterans and park rangers. The teams were deployed to track tiger hunters in the forest and use hidden cameras to record transactions in the city. Thanks to the success of Galster’s original anti-poaching units, as well as a dozen additional units now funded by a consortium including the World Wildlife Fund, the Siberian tiger population has risen to 400.

Unfortunately, the hunters never disappeared, as Galster discovered in April 2000 when he went back to Vladivostok to renew WildAid’s contracts with the Phoenix Fund, an umbrella group he helped establish that funnels money to smaller, non-governmental species-protection outfits in Russia. He intended to stay only a few days, but one of the anti-poaching teams he’d organized had identified a rogue policeman from the neighboring town of Ussurisk, 40 miles to the north, who was moving tiger and bear parts to a Chinese mobster across the border in Jilin province. The Vladivostok police alleged that the Chinese dealer had paid off the cop, Vladimir Korolev, to murder a competitor. Now they wanted Galster to pose as an American buyer, wear a wire, and catch Korolev in an illegal transaction.

Galster couldn’t refuse. Sergei Bereznuk, director of the Phoenix Fund, posed as his assistant. After making contact with Korolev, the men drove to Ussurisk in the middle of the night to meet him. They were wired with old Soviet listening devices that transmitted to a backup team of cops and government intelligence agents perched in a nearby van.

“The cop finally pulled up, and I could see he was a big fat guy driving an old, crappy Toyota,” Galster recalls. “He took us across town to an empty safe house and showed us some tiger skins. They were huge. All I was thinking was, This is such great stuff! I hope my camera doesn’t malfunction.”

It didn’t. On the grainy video, Korolev unrolls his wares and spreads them on the floor: skins from two massive adult male tigers, with their jaws frozen in wide snarls. Galster kneels down to examine them.

“How much tiger skins you need?” Korolev asks, with Bereznuk translating. “How much length? [I] can do as much as you want.”

“As many skins as I want?” Galster asks.

“Yes, as many skins,” comes the answer. “What coat you want? Winter or summer?”

Galster opted for summer, and the two agreed on a price of $3,000 for two skins, plus another $100 as a delivery fee. Delivery was key; the undercover team needed to get the trafficker back to their Vladivostok jurisdiction to arrest him. Galster gave Korolev $100, and they left in two cars for the Vladivostok Hotel, where Galster was staying.

That’s when the ancient Soviet transmitters the pair were wearing blinked out, cutting them off from their colleagues in the van. “We didn’t have $3,000 in cash to pay this guy off, so we were getting nervous,” Galster says. “Then we got back to the hotel and—shit!—there was a car from the undercover team in the parking lot that he might have recognized.” Galster and Bereznuk told the rogue cop they were going upstairs to fetch his money, but when Korolev saw some cops in the lobby greeting them familiarly, he revved up his car and bolted—with the skins. Luckily, the backup team was able to pull him over and make an arrest.

During a hearing held in a Vladivostok court in November 2000, Korolev testified that the skins in his trunk didn’t belong to him. Despite Galster’s damning video, he avoided jail time. But the operation still had a major impact: The skins were confiscated, and the Ussurisk police later fired Korolev. In a country where policemen are viewed as untouchable because they often live up to their reputation for corruption and ruthlessness, the arrest made national news.

“The biggest deal was the publicity,” recalls Bereznuk, speaking from his Vladivostok office. “The trafficker wasn’t just an ordinary cop. He had been in charge of a department that surveilled foreigners. That he was fired sent a big message to some traffickers: Even high-level bureaucrats could be caught and disgraced.

“Steve was one of the first foreigners I’d ever met in the flesh,” Bereznuk adds. “I watched him go out on patrols, ask a lot of questions, raise money for us, volunteer his time to other groups, analyze the poaching situation, develop a solution, and personally implement it. He wasn’t a huge, disinterested investor throwing money at us from abroad. He was involved on the ground. That’s when I decided he is not your average American.”

LIKE MANY CONSERVATIONISTS, Galster zeroes in on charismatic megafauna—”indicator species,” he says, that forecast the situation of the ecosystems they dominate. He instills this idea in the rangers WildAid trains, which is why the guards who patrol Khao Yai and Bokor national parks focus much of their attention on bears, tigers, clouded leopards, and elephants. Khao Yai’s elephant-monitoring team heads into the forest each week to make sure the park’s 120 pachyderms are accounted for. But animal-defense patrols are not enough for an armistice; the whole culture of poaching needs to be undermined as well.

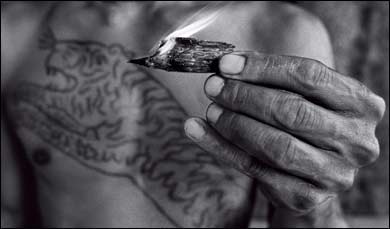

At the end of a muddy road in Khok Saard, a village on the outskirts of Khao Yai, 118 miles north of Bangkok, Sompong Prachopchan is standing over a boiling vat, stirring mushrooms. At 39, he’s a new convert to the agrarian way. There’s a tiger tattooed across his chest, a reminder of his former life, that of a mercenary for the Thai military who fought the Khmer Rouge and other insurgents. Throughout the eighties and nineties, when he wasn’t doing that, he was poaching protected tigers, bears, elephants, and barking deer.

That all ended three years ago when Sompong was caught with an 18-pound haul of aloe wood by a WildAid-trained ranger patrol in Khao Yai. After his arrest and trial, a few days in jail, and a hefty fine, he was enlisted to work on the group’s community-outreach project. In this program, villagers who used to forage in the park for food, or hunt endangered species to sell to traffickers, now receive seed money for alternative livelihoods, like growing flowers and mushrooms.

Standing under a plastic tarp in the pouring rain, Sompong stops stirring and walks over to a table piled with chrysanthemums. “When I was a poacher, a middleman sent me into the forest to get aloe wood,” he says. “We all knew that if we shot an elephant or a tiger, he would buy that, too. But after I was arrested, I decided to leave poaching. If we keep on destroying the forest, there will be none left for the next generation.” As he talks, Sompong rolls bunches of flowers into old newspapers. The bouquets will be sold in local markets, the profits to be shared among the villagers. Galster says he tapped the ex-mercenary to work on the village-conversion project partly because he figured “he would have cred among fellow poachers,” and partly because he views the fight against wildlife trafficking as a counterinsurgency movement.

“What you do is apply counterinsurgency war-gaming to poaching and trafficking,” he continues. “The poachers and traffickers are the insurgents; the local villagers are their moral support; and the big boss trafficker at the top of the food chain is the logistical support, funneling money and weapons. Counterinsurgency teaches you that the people fighting your war really have to believe in it themselves. You can’t just be giving them rice, because they’ll see right through you, take your rice, and still go into the park and poach animals. For it to work, you have to be genuine.”

Sompong seems to believe in Galster’s conservation model, though he admits to keeping his old aloe-wood saws around for a rainy day. “I am earning ten times less than I made poaching, but that’s OK,” he says. “My new job is influencing poachers in my own village and in other villages to find different work. Some poachers are changing their attitudes, and some are waiting to see if this works out or not.”

At this, he points to a man walking down the road. It’s the middleman who used to buy Sompong’s aloe wood; Sompong still owes him 6,000 baht (about $153) for helping pay his poaching fine. Later that day, when Galster learns that Sompong is still paying off the vig to his old boss, he quickly and quietly sends the reformed poacher an envelope with enough cash to cover the debt. WildAid’s model park program, it turns out, is called Surviving Together.

And as Galster knows, not everyone in Khok Saard is willing to be reprogrammed. “The women in the village have turned into a capitalist force, reinvesting their profits back into the business. But some of the men are still poaching. The good news is, the men don’t want to risk getting caught, so they’ve stopped carrying guns into the forest, which means we are documenting fewer animal kills.”

FEWER ANIMAL KILLS is also the goal of WildAid’s new U.S. print-ad campaign, which graphically depicts a hornless rhino bleeding on the concourse of Grand Central Station and a tiger oozing blood on the steps of the New York Public Library. Whether these will shock jaded Americans into writing checks remains to be seen, but a similar WildAid campaign a few years ago, against the consumption of shark-fin soup in Thailand, got that entire nation’s attention.

Shark-fin soup is an expensive delicacy throughout Asia that’s served to honored guests at birthdays and weddings. The key ingredient comes from a cruel practice: slicing the fins off live sharks and throwing the carcasses back in the ocean. Just about any shark will do. In 2000, after Peter Knights put out a report based on data from the UN Food and Agriculture Organization, estimating that fishermen kill more than 50 million sharks per year worldwide, Galster called on the Thai government to ban shark finning. When there was no response, he escalated with a provocative public-awareness campaign created by J. Walter Thompson, the international advertising powerhouse based in New York.

The ads ran in Thai newspapers and magazines in July 2001; the most provocative one depicted Chinese tombs in the shape of upside-down soup bowls, with the tag line “Tests show that shark fins sometimes contain mercury, making this endangered species more dangerous to you dead than alive.”

The Thai press went crazy, sales of shark-fin soup initially dropped by 30 percent, and Bangkok’s soup purveyors organized into a group called the Association of Shark Fin Restaurants. The restaurateurs produced counter-research claiming that their shark fins were mercury-free; then they filed a lawsuit against Galster, his PR assistant, and J. Walter Thompson to recover what they claimed were $3 million in losses. The suit is still winding its way through the Thai courts. In the meantime, WildAid has successfully lobbied CITES to get whale sharks listed as a protected species, and is trying to get the great white listed as well.

“When we designed the ad campaign, our feeling was that we would see a slow build. After all, by telling Thais not to eat shark-fin soup, we were asking them to change a deeply ingrained social and cultural behavior,” says Marc Capra, 46, who was managing director of J. Walter Thompson’s Bangkok office at the time. “But the reaction was dramatic. Even people of Chinese heritage who used to take the soup for granted were appalled and could not help being emotionally affected.” Lately, Capra has broadened J. Walter Thompson’s relationship with WildAid, creating an international pro bono campaign for their Asian Conservation Awareness Program. Hard-hitting print ads currently running in Malaysia show humans bleeding where noses, genitals, or other appendages have been cut off. Sample tag line: “Your hand is chopped off. Infection sets in. Then they cut off the other hand. You’ve just lived a bear’s last few moments.”

Galster excels at building such partnerships. Last September, he convinced Thailand’s environment minister, Prapat Panyachatraksa, to sign a memorandum of understanding to cooperate with WildAid on reducing wildlife crime. It seemed like a mere formality, but in October, Prime Minister Thaksin Shinawatra gave the go-ahead to unleash the biggest crackdown on wildlife trafficking in Southeast Asia. Since then, WildAid has helped the government save more than 35,000 animals, and the Thai police have arrested dozens of traffickers.

“It’s been very exciting,” Galster says. “The police have been busting people every day. After a tip to our hotline, I went with 50 investigators to a slaughterhouse in Sai Noi [a town north of Bangkok], where we found live and dead animals, tame bears, tigers in cages ready to be slaughtered and sent as meat to exotic restaurants, and tiger cubs that looked wild.” Police netted a gruesome haul: 100 pounds of tiger bones, 46 pounds of newly slaughtered tiger meat, three tiger skins, and 20 black bear paws, still bloody.

WILDAID DIDN’T INVENT the idea of wildlife protection; the concept originated decades ago with farsighted field biologists. But the group has managed to turn aggressive protection into one of the hottest trends in conservation.

“In human society, if you want to stop murder and lawlessness, you create a police force. Same goes for stopping animal crime,” says Alan Rabinowitz, the 50-year-old director of science and exploration for the Wildlife Conservation Society, which manages wildlife habitats all over the world from its base at the Bronx Zoo.

Rabinowitz ought to know. A well-known big-cat expert and author of such books as Chasing the Dragon’s Tail: The Struggle to Save Thailand’s Wild Cats, Rabinowitz first saw the need for strong, sustained species protection when he traveled to Belize in the 1970s to study the country’s dwindling jaguar population. His research, he soon realized, had little practical impact on the jaguars’ survival. So he established the world’s first jaguar preserve and raised money to protect its boundaries.

“When I started my fieldwork, nobody in conservation wanted to talk about protecting parks,” Rabinowitz says. “Even today, you’d never see a line item in a conservation budget for guns and bullets. But in part due to WildAid, it is now acceptable to fund ranger training and salaries. If species are to survive, a national park has to be a truly inviolable wildlife core protected by well-trained people.”

This same debate—armed and active enforcement versus passive security—has roiled the conservation ranks in Africa for decades, and has led to a wide array of protection schemes on that continent. Now, with WildAid pushing its hardcore protection agenda, wildlife groups are moving more forcefully into the protection game in other parts of the world. Since 1999, the Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS) has been working with the Thai government to improve anti-poaching enforcement and wildlife monitoring with the border patrol; and in 2001, Conservation International started funding ranger training in Cambodia’s Cardamom Mountains, turning former Khmer Rouge guerrillas into anti-logging brigades.

“Science-based organizations such as WCS are increasingly realizing that we have to get into enforcement issues, and WildAid is the core team that has experience we can draw on,” says Elizabeth Bennett, 47, director of the hunting-and-wildlife-trade program at the WCS. “But protection can have an impact only if it works in concert with biological monitoring and a deep understanding of ecosystems. We’re learning a lot from WildAid, but I’m not entirely sure how much they are learning from us.”

She’s right. WildAid is not a replacement strategy for the science-based conservation movement; it’s been designed to plug what Galster and Gauntlett see as gaping security holes in wildlife protection. But there are still some in the conservation community who think that strategy is shortsighted.

“Protection is WildAid’s niche,” says Sybille Klenzendorf, director of the World Wildlife Fund’s tiger conservation program. “But that’s a kind of first step you take when a species such as the tiger is facing imminent extinction from hunters. It’s putting out a fire….Now the direct threats to tigers have become habitat loss and loss of prey. So we moved into that area.”

Once they’ve put out these fires, though, Galster says WildAid’s plan is to work itself out of existence—maybe even by 2030. He hopes the group becomes redundant, turning its overseas offices into locally run NGOs with all-local staffs, as he has already done with the Phoenix Fund in Russia. It is, perhaps, WildAid’s most radical idea.

“One of the differences between us and mainstream U.S. conservation groups is that they still believe foreign governments need to be educated to step up wildlife security,” Gauntlett explains. “But governments in Third World countries already want to protect their parks. Once groups like WildAid give them budgetary and training support, we’ll be able to bow out and let those governments entirely take over protecting the wildlife within their borders.”

In the meantime, Galster is hatching WildAid’s grandest project yet: unplugging what he calls “the Chinese vacuum cleaner, sucking up Southeast Asia’s wildlife left and right.” It’s widely known that practitioners of Chinese traditional medicine use tiger bones and bear gall bladders as remedies, and that tiger and reptile meat is considered exotic cuisine to some Chinese. What’s less well known are the numbers. Traffic, the UK-based monitoring group, reports that during 2000, 20 tons of turtles were shipped from Indonesia to China every week. And in just seven months in 2002, Thai officials intercepted 1,800 mammals and 21,000 reptiles bound for their voracious neighbor to the north.

Galster’s goal is to level the illegal wildlife trade in Asia over the next five years—corresponding with the buildup to the Beijing Summer Olympics in 2008—by getting indigenous NGOs to work across borders and fight poachers, traffickers, and consumers. In addition to the programs they’ve already got up and running in Cambodia, Thailand, and Russia, WildAid is hoping to beef up wildlife-security operations in Myanmar, Malaysia, Singapore, and Taiwan by stitching together a $10 million grant from a number of sources, including the Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund (CEPF), a consortium that includes the MacArthur Foundation, the World Bank, and the Japanese government, which has already given them $250,000. It sounds grandiose, but the CEPF was set up precisely because its donors concluded that the only way to save endangered habitats was to sponsor creative broadband approaches.

“We are at a point where conserving biodiversity hot spots is so complex that no single group can go it alone,” explains Jorgen Thomsen, senior vice president of Conservation International and the executive director of the CEPF. “Direct support to civil society groups from a partnership of public and private funds has a higher probability of success for protecting both species and habitats, especially when you are dealing with ecosystems that straddle the boundaries of several countries. China may well be a very big market for wildlife, from tigers to turtles, coming in from abroad, but you can’t look at the China consumption issue separately. It’s tied to he markets in neighboring countries which are suppliers.”

GOOD THING, THEN that in Southeast Asia, suppliers don’t keep a very low profile.

One day last September, Galster and Tim Redford, director of WildAid’s Surviving Together community-outreach project, decided to check out Tachileik, a bazaar just across Thailand’s northern border with Myanmar that’s infamous for species trafficking. Myanmar is one of China’s biggest wildlife suppliers, but to find what they were after, the two men had to wade through long rows of open-air stalls jam-packed with knockoff Nikes and Nikons, pirated gaming CDs and DVDs, mountains of Jockey shorts, porn videos, fishing rods, polyester nightgowns, and fake tiger penises carved from wood. Soon enough, Redford spotted some actual wildlife.

“That’s a golden cat skin, and that looks like a clouded leopard skin with a very unusual melanic coat variation. That’s pretty damn rare,” he said, pointing to a five-foot-long piece of soft beige fur with bold, cloud-shaped gray spots. Because of poaching and habitat destruction, the clouded leopard is endangered all across Asia; according to the Red List, there are fewer than 10,000 of the animals left on earth. Standing in Tachileik, it was not hard to understand why. In a country where the average per capita income is $300, this skin could bring in about $114.

When Galster happened upon a stall with three adult clouded leopard skins on display, he knew he was on to something. The shop girl said her parents owned the stand and kept several dozen more skins back at their house, but that she was unwilling to take a stranger there. An hour later, after inspecting every lane in the market, Galster found the house on his own.

The ground floor was dark and musky, with floor-to-ceiling glass cabinets crowded with 18th- and 19th-century British colonial china and hand-painted wooden bowls piled next to necklaces of yellowing animal teeth. Galster spotted a fearsomely sharp horn from a serow—an endangered woolly-coated wild mountain goat—and Redford offered the family $150 for it, but they weren’t selling. They could get much more from gamers who use the horns to make spurs for illegal cockfighting, another piece of information for Galster to add to his jigsaw puzzle.

Because Galster already had spoken to the shopkeeper’s daughter, who was now there too, the woman agreed to show him the rest of her stash. She sent the girl up a rickety flight of wooden steps to the family’s quarters. A few minutes later, she came back down staggering under the weight of a large plastic box, which she dropped behind the counter. The stench of mothballs enveloped the store as she pried off the lid, revealing a stack of carefully packed skins.

Normally unflappable, Galster looked painfully surprised as he removed the first skin and gently unfolded its limp head and paws on the counter. There were 30 clouded leopard skins in the box, and the merchant volunteered that she received a similar shipment of 30 skins every two months, selling about one skin every other day. “We used to think the traders always had the same skins up all the time, year after year. But she’s selling 15 per month, and this is just a small store,” Galster whispered. “Even if she is the main dealer in Tachileik, which I doubt, that’s a huge amount.”

Galster told the woman he would return when he figured out how many skins he wanted to order, then he and Redford crossed back to their hotel on the Thai side for a postmortem. He seemed depressed and distracted. Tachileik had made him realize that WildAid needs to ramp up its Asian operation substantially if it’s going to be more than a short-term offensive in the war on poaching.

“This is bad,” Galster concluded. “The fact that she was selling clouded leopard skins means they are running out of tiger skins in Burma, because when one species is knocked out, they go on and knock out the next species down. You don’t see people every day with animal skins on their floors or up on their walls, so you’re not so likely to add the numbers up. I think for once we have been underestimating. The situation with skins is much worse than I thought.”

For the first time in a long while, Galster’s vaunted intelligence had been wrong. The world’s endangered species might yet be protected from black-market traffickers and mom-and-pop dealers, but that day seemed a long way off. He sank back onto the bed and stared up at the ceiling. “It’s not about how long you live,” he said. “It’s about what you get done.”