The accused threads his way up the steps of the stone Palais de Justice in the ancient Mediterranean city of Montpellier. He has receding sandy hair and a comically long walrus mustache, wears a fey little yellow neck scarf, and clutches a pipe. Muscular young activists in yellow T-shirts escort him past dozens of aggressive TV cameramen, all cursing through their cigarettes and jockeying for a better angle. One trips and is trampled by the others. Halfway up the stairs, the defendant turns, smiles into the cameras, and gazes over the several hundred protesters gathered on the street below.”Tous ensemble! Tous ensemble!” they are shouting. They, too, are wearing fey little yellow neck scarves.

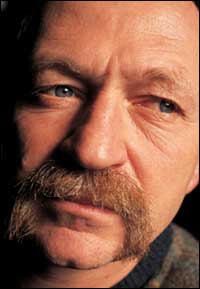

“Je suis un paysan”: Peasant manqu├ę Jos├ę Bov├ę photographed at a farm on France’s Larzac plateau.

“Je suis un paysan”: Peasant manqu├ę Jos├ę Bov├ę photographed at a farm on France’s Larzac plateau.

The defendant grins, gives a thumbs-up, and pumps his fist. The crowd goes wild. Their hero is, with the possible exception of President Jacques Chirac, France’s most famous political personality. He has been compared to Voltaire and to Robin Hood; the Socialist Party has urged him to run for President. His name is Jos├ę Bov├ę. He makes cheese.

It is the morning of February 15, 2001, and Bov├ę, 47, and his nine (virtually unnoticed) codefendants are appealing their sentences for criminal vandalism convictions, charges resulting from an August 1999 protest in which a McDonald’s under construction just outside the farming village of Millau was disassembled, bolt by bolt, and carted away. The McDonald’s Ten are all members of France’s national Conf├ęd├ęration Paysanne, the militant small-farmers’ union Bov├ę cofounded in 1987. Bov├ę, who was sentenced to three months in prison, is unapologetic. He took apart the McDonald’s to protest American imperialism, its trade policies, and the general, noxious spread of malbouffe. Malbouffe, Bov├ę has said, “implies eating any old thing, prepared in any old way. … Both the standardization of food like McDonald’s—the same taste from one end of the world to the other—and the choice of food associated with the use of hormones and GMOs [genetically modified organisms], as well as the residues of pesticides and other things that can endanger health.”

This week, in addition to hearing Bov├ę’s McDonald’s appeal, the French justice system will consider a prosecutor’s appeal of Bov├ę’s suspended sentence in his conviction of holding hostage three agriculture officials whose policy decisions he disliked. (Their imprisonment in an office in the Aveyron regional department of agriculture lasted ten minutes.) A week ago, a judge gave him a ten-month suspended sentence for leading a protest that involved breaking into a research laboratory, spray-painting computers, and uprooting trays of transgenic rice. Bov├ę already spent nearly three weeks behind bars after his arrest for the McDonald’s insurrection. Unlike the rest of the McDonald’s Ten, he strategically refused bail, milking the public sympathy and media attention that followed.

Since the storming of the McDonald’s, “Bov├ęmania” has spread as quickly as foot-and-mouth disease. Bov├ę has been interviewed on NPR’s All Things Considered and assessed by policy experts on Nightline with Ted Koppel. Strangers shout his name. During the November 1999 anti┬şld Trade Organization protests in Seattle, he delivered fiery speeches, linked arms in human chains, and gave away 500 kilos of Roquefort smuggled in from France. Last year, he traveled to India, Turkey, and Madison, Wisconsin (cheese capital of the U.S.A.!), to rouse farmers against globalization. In January 2001, he speechified at the World Social Forum held in Brazil in opposition to the CEO-heavy World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland. For good measure, he led hundreds of campesinos on a midnight raid to uproot genetically engineered soybean plants on farmland owned by the Monsanto Corporation.

Bov├ę’s free-market enemies have dismissed him as a mercenary, a poseur, and a nationalistic xenophobe. But as Europe convulses in a deepening agricultural crisis, as Britain torches and buries more than a million farm animals this year alone, Bov├ę’s star only ascends higher. Wielding his campy blend of folksiness and intellectualism, along with an unerring instinct for political theater, he has elevated France’s debate over food purity and traditional agriculture to the highest levels of the national agenda. France, partly in response to Bov├ę’s charming commando campaign, has conducted a more focused, urgent debate over agricultural globalism, bioengineered crops, tainted beef, and farming contagions than any country in the world. Even the staid Parisian newspaper Le Monde was moved to proclaim, “It is a cultural imperative to resist the hegemonic pretenses of the hamburger.”

And so, on this late-winter morning, Bov├ę, a veteran of four decades of left-wing mischief making, turns away with one last wave and enters the Palais de Justice knowing that, at least for the moment, history is on his side. He is the spirit of the Revolution and of badass environmentalism—a cell-phone wielding, worldwide rabble-rousing, draft-dodging former hippie. He has a wife, a girlfriend, a small army of attorneys, and the ear of the prime minister. He is very French.

Mad cow disease, or bovine spongiform encephalopathy, was first discovered in British cattle in 1986. A similar infection, scrapie, had most likely jumped species after sheep offal was fed to cows; the disease, which riddles the host’s brain with holes, spread further when the remains of diseased cows were fed to other cattle. More than a thousand cases a week were being reported in the United Kingdom by 1993. Only a handful of French people have contracted new-variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease—the fatal nervous-system collapse that stems from eating BSE-infected beef—as opposed to 90 in Great Britain, but 161 mad cow cases were documented in France last year (and 1,101 in Britain). When several French supermarket chains revealed last October that they had stocked meat from a contaminated farm, national beef consumption dropped 40 percent.

The mad cow disaster, however, has been dwarfed by this year’s outbreak of foot-and-mouth disease. The first confirmed case of the nonfatal skin infection, in which animals develop sores, lose weight, and stop producing milk, turned up on February 20, 2001, in pigs in Northumberland, England. They had dined on restaurant slop containing illegally imported meat from Asia, where foot-and-mouth is common. The disease poses no risk to humans, but is highly contagious and economically devastating; this spring, as British farmers slaughtered up to 30,000 animals a week, scientists warned that 30 percent of the nation’s farms may be hit by the epidemic, and half of its livestock sacrificed.

It wasn’t long before foot-and-mouth jumped the Channel. On March 13, France confirmed its first case at a dairy farm in Laval, where the cows had been grazing near imported British sheep, and has since sent 50,000 animals to the pyres. Eight days later, Dutch officials announced the Netherlands’ first case of foot-and-mouth.

But what does any of this have to do with the construction of yet another McDonald’s? Bov├ę’s beef was not with McDonald’s per se, but in August 1999 the fast-food chain was a convenient scapegoat. Europe had weathered a number of food scares that summer: Benzodioxin had turned up in Belgian chickens, and, in an unrelated and unsolved incident, 14 Belgian schoolchildren had fallen ill after drinking Coca-Cola, prompting a three-country ban on Coke products. Mad cow worries lingered. The immediate trigger for the assault, however, was a minor trade war between France and the United States, in which a chief victim was Roquefort cheese, the pungent blue made from sheep’s milk and produced only in Bov├ę’s home region, the Larzac—a rugged, heath-covered plateau in Midi-Pyr├ęn├ęes about halfway between Toulouse and Marseilles. That July, after France renewed its refusal to import American hormone-fed beef, the U.S. slapped a punitive tariff of 100 percent on 77 French agricultural products, including Roquefort. “We didn’t understand why the U.S. did this thing,” Bov├ę gripes. “It was a real provocation.” Although McDonald’s restaurants in France use only French, hormone-free meat, many there view the chain as the embodiment of the American 800-pound gorilla. (There are 850 McDonald’s outlets in France, and 1.5 million people—out of a population of 60 million—eat there daily, malbouffe ou non.) When Bov├ę and his fellow radical sheep farmers heard that a “MacDo” was going up in their backyards, they were insulted.

And so, on the morning of August 12, 1999, after informing police of their plans, the farmers, accompanied by several hundred supporters, rumbled in their tractors and forklifts and Citro├ź to the site of the nearly completed McDonald’s. With chainsaws, chisels, and screwdrivers, the crowd, kids too, set about removing windows, prying off tiles, dismantling walls, and taking down signs. “The whole building appeared to have been assembled from a kit,” Bov├ę recalled with mild Gallic disdain. “The structure was very flimsy.”

The event was made for television. There was Bov├ę, lugging around a broken McDonald’s sign bigger than he was. There was the parade of farm vehicles loaded with debris, which was gently deposited on the lawn of the Millau regional prefecture. There were the farmwives, cheerfully passing out Roquefort snacks to drivers and passersby. “Every single symbol was there,” Bruno Rebelle, director of Greenpeace France, says admiringly. “A small farmer, a big fast-food, low-quality, highly globalized company.”

“You see,” he adds, “in the U.S., food is fuel. Here, it’s a love story.”

NEEDLESS TO SAY, THE McDONALD’S Corporation was not amused—and is still not amused. “We are so the wrong target,” says company spokesman Brad Trask from global headquarters in Oak Brook, Illinois. “Our French outlets are virtually entirely locally sourced and Bov├ę knows that quite well. You’ll find no better supporter of local agriculture than us.” Besides, Trask sniffs, “Bov├ę is a gentleman farmer who got his farm by squatting and falling into it. He’s an unlikely spokesman.”

Bov├ę, who has been making powerful enemies his entire adult life, is indeed more complicated than the gruff peasant he projects.The son of two crop scientists, Bov├ę lived in Berkeley from the age of three until he was seven, while his parents, Josy and Colette, studied microbiology at the University of California. His two younger brothers grew up and got normal jobs, but Jos├ę made a career of rebellion: At 16, he got kicked out of Catholic school in a Paris suburb for writing a short story about a not-so-godly hero with a fondness for drugs. Two years later, in 1971, he dropped out of Bordeaux University after one month. “I thought I had other things to do,” Bov├ę says—things like campaigning for disarmament, fighting the French military’s narrow definition of “conscientious objector,” and hanging around Bordeaux reading Thoreau and Gandhi. He met his wife, political science student Alice Monier, when they found themselves painting a protest banner side by side.

It was their antimilitary activism that drew Alice and Jos├ę to the Larzac. In the fields outside the town of Roquefort-sur-Soulzon, native ewes graze native grasses, and the cheese made from their milk is infused with the venerable fungus Penicillium roqueforti and aged for months in limestone caves. As with French wines, the operative word is terroir (“of the earth”)—the very essence of the soil in which a product is grown.

In the early 1970s, a large swath of this sacred cheeseland lay in the path of a proposed army base expansion. Jos├ę and Alice joined scores of students, socialists, feminists, and general lefties in the Larzac farmers’ fight. In February 1976, married and with an infant daughter, Marie, the couple moved to the Larzac full-time to squat on land purchased by the army. (They’d been hiding out on a collective farm in the Pyrenees until then, so that Jos├ę could dodge the draft.) They occupied an old farmhouse in the village of Montredon, and Bov├ę busied himself planning pranks. That June, he and 20 cohorts broke into a military camp and stole records documenting farm foreclosures; the next summer, he piloted one of 90 tractors in a convoy that occupied the base’s firing range. By the time the government eventually backed down, in 1981, Alice and Jos├ę had another daughter, H├ęl├Ęne, and, with four partners, a robust flock of sheep producing fine Roquefort milk.

With the army off their backs, the Larzac farmers turned their attention to more general reform, and in 1987, Bov├ę and fellow farmer-activist Fran├žois DuFour helped found the Conf├ęd├ęration Paysanne. For the next decade, the new national farmer’s union lobbied for small farming, created co-ops, and fought the increasing use of the milk-yield hormone bovine somatotrophine (BST).

In January 1996, as the mad cow crisis roiled Europe, Bov├ę’s genius for symbolism reached new heights. He led Gertrude and Laurette, a cow and her calf, to the steps of the Mus├ęum National d’Histoire Naturelle in Paris to dramatize how normal farm animals would be rendered obsolete if the import of hormone-fed meat was permitted. That September Bov├ę led farmers into the Central Customs Service in Toulouse and made off with documents uncovering the large quantities of British animal feed being shipped into the country. In January 1998, Bov├ę and others broke into a facility in Nerac owned by the Swiss company Novartis and destroyed genetically engineered corn seeds. In June 1999, just before the sacking of the Millau MacDo, he pulled the transgenic rice caper at the research lab, one of the cases on the docket in Montpellier.

In the aftermath of the McDonald’s incident—his third arrest in two years—Bov├ę transcended regional notoriety: Thirty thousand Bovistes thronged Millau for the first trial of the McDonald’s Ten in July 2000. The defendants rolled into town on a cart pulled by a tractor, echoing the preferred means of delivery to the guillotine. Now Bov├ę is on his way to international celebrity. Having sold 100,000 copies in France, his book, Le Monde N’est Pas Une Merchandise, cowritten with Fran├žois DuFour, is being translated into nine languages, including Turkish, Japanese, Korean, and Catalan. The U.S. version, The World is Not For Sale, will be published by Verso Books this summer.

Only in France, and perhaps Central America, do green peasant revolutionaries become megacelebrities. Would Americans wear fey little neck scarves for Ralph Nader? Bof. Ecoprotesters here risk jail time to save endangered lynx. In France they do it for mold.

BETWEEN TV APPEARANCES and strategy sessions with his attorneys, Bov├ę is hunkered down in a faux-leather couch, sipping espresso and smoking, in the lobby of his hotel in downtown Montpellier. In his plaid shirt, green wool V-neck sweater, and jeans, with that ubiquitous pipe, Bov├ę looks out of place amid the mod decor. As we talk, he alternately ignores and courts the swell of reporters—TV crews, the Paris papers, the BBC—milling about the lobby. He seems impatient, like he’s got more important McNuggets to fry. He’s been 18 months without a vacation, he complains. He’s tired. But there’s work to be done.

“In the Larzac we have been fighting together for 20 years, and people know how to fight. They won’t be scared to fight again,” he says. “Farmers are losing 15 million francs each year because of the United States. There is no international court where we can say we don’t agree. That’s why we demonstrated against McDonald’s.”

Roquefort cheese, Bov├ę points out, is as opposite as you can get from cheap beef. “Terroir is a human story, the story of the land. It means not just geography, but a special way to make a product. The agricultural industry wants to put all this out of business and keep a little place for terroir, only for rich people.” Meanwhile, he says, “American consumers care only about price, not about what kind of food. People are eating out more and more, eating quickly, having problems with health and 30 percent obesity. The problem is the industrial way of making food.”

“Making cheese,” on the other hand, “you know exactly what you’re doing.” Bov├ę’s agricultural solutions are extensions of this philosophy of self-reliance. “Each area in the world should feed its own population, not the whole world,” he says. “One of the first things we have to do is stop the subsidies and just feed our own population. … Cheese and wine have no subsidies. People who want to buy it, buy it. People who don’t, don’t.”

All week I’ve been asking Bov├ę to show me his Montredon farm, to see how his two careers as protester and farmer have connected. First he tells me, “Later,” in that noncommittal French way, and then, “I’ve stopped inviting media to my home.” It’s true, the attention is wearisome, but life in the spotlight has also made it difficult for Bov├ę to juggle increasingly complex social obligations. When I drive through the Larzac’s rolling grasslands and lonely limestone outcroppings to see the farm where it all began, I find Bov├ę’s wife and longtime comrade-in-arms, who is no longer one of his fans.

A petite, pretty woman with a smooth, warm face and a grayish bob, Alice Monier invites me into their 130-year-old stone farmhouse, on a village lane ending abruptly in fields. With a glance at her two visiting daughters, Marie and H├ęl├Ęne, smoking cigarettes by the fireplace, she presents me with a long cri de coeur published last year in the Conf├ęd├ęration Paysanne newsletter, in which she scathingly makes accusations of infidelity—Bov├ę, she says, left her for another woman last June—and recounts her subsequent emotional abandonment by Conf├ęd├ęration Paysanne. Not only is Monier disgusted with Bov├ę, she is disgusted with the whole pack of farmer-activists, the whole damn “union of machos.”

Even some of the machos have grown disillusioned with their local star. A couple of activists have jumped ship to work with other organizations, citing unhappiness with what they perceive as Bov├ę’s media-lapping. But most are still firmly behind him. In another old stone house not far from Montredon, I catch up with McDonald’s codefendants Richard Maill├ę, a pink-cheeked fellow with a Caesar haircut, and Jean-Emile Sanchez, a Cat Stevens look-alike with limbs like tree trunks. This is his family’s farm, Maill├ę, 34, tells me; the land has been cultivated since the 12th century. (His graying father, L├ęon, brandished a chainsaw during the Millau incident.)

I ask whether Bov├ę gets too much credit. “Yes,” answers Sanchez quickly. “People are becoming more interested in his persona and forget about what the movement’s about. He’s not the charismatic leader. This is not only about him.”

Adds Maill├ę, “They think if they send just him to prison, they will destroy the movement. But the movement is bigger than that. We will continue to destroy more crops. It will be fabulous.”

The Maill├ęs recently decided to produce organic ewes’ milk, and so they have switched from selling it to a Roquefort company (which, Richard scoffs, is highly industrialized and not organic) to a local producer. He cheerfully spreads the cheese on bread and passes it around.

Sanchez takes a bite and makes a face. “You can taste the nuts in the bread,” he says. “The cheese is not as strong as it should be.”

Maill├ę is crestfallen. “I know,” he admits sheepishly. “It’s a new company, and this cheese is only aged a month and not three or four months because there’s not enough production to fill the orders yet.”

“We’ll sell it to the Germans,” he adds, brightening. “They’re not connoisseurs.”

THE MONTPELLIER district courtroom is small. To the left sit the McDonald’s Ten, their army of attorneys (paid for by the Conf├ęd├ęration Paysanne), and their families and friends, including Bov├ę’s parents, small and white-haired, who watch cross-armed from the back of the room. To the right sit the prosecutor and representatives of the print media (no cameras, please). Strains of festive zydeco and reggae waft in from the plaza next door, where the mad cow┬ştumed, sign-waving crowd (“Liberez Les Inculpes!”; “Cannabis, C’est Bon!”), will soon swell to 15,000.

Inside, the three justices, one woman and two men in black robes and white cravats, sit at a high bench. Above them looms a huge fresco of a bloody dead body in a toga, a guilty-looking miscreant, and a buxom puella holding the scepter of justice.

Bov├ę’s scraggly codefendants look more like Aerosmith than farm boys. They are here to demand equal punishment for Millau, instead of the individual sentences they received last June, which ranged from nothing to three months. “We want either three months for all or nothing for all,” Sanchez said earlier. “It’s a group thing.”

It is the intention of the defense to paint the farmers as the conscience of the nation, citizens whose acts of civil disobedience, while perhaps technically illegal, are nevertheless forgivable cries of truth in an otherwise ruthless and technocratic world. Meanwhile, in the hostage case, the prosecutor will demand that Bov├ę’s suspended sentence for detaining the agricultural officials be replaced with real jail time.

The chief justice motions for Bov├ę to approach the bench and give a statement on the hostage affair. “Je suis un paysan,” Bov├ę intones with some bravado. He says that he only wanted to discuss with the officials their disappointing position on European Union farm policies. “We closed the doors and kept them from leaving in a symbolic way,” he says. “We knew we couldn’t hold the hostages long because we were in a prefecture surrounded by riot police.” Judge: “Could things have gotten out of hand?” Bov├ę: “No, it was a pacifist thing. We held a mutton roast on the lawn!”

In the afternoon, the chief justice summarizes the McDonald’s incident: He mentions the tractors, the forklifts, the graffiti spray-painted, the doors removed. Bov├ę is the first to take the stand. “McDonald’s,” Bov├ę says, “is the symbol of standardization of food. What we did was like the Boston Tea Party.” The prosecutor, a burly man, is turning red, but it’s not his turn to speak.

“McDonald’s is a French investment,” the chief justice argues, “with local jobs, local meat, local produce.” Then he switches tack. “What did you think of the headlines saying you sacked the place?”

Bov├ę: “It was an exaggeration. We didn’t sack it. We dismantled it.”

Judge: “What does ‘dismantle’ mean? When you took off the tiles, some of them broke.”

Bov├ę: “What did it mean when they dismantled the Bastille?” The crowd guffaws.

The prosecutor can’t help himself. “Stop fooling around,” he commands Bov├ę.

When he finally gets his turn, he paces artfully. “║┌┴¤│ď╣¤═° is a carnival,” the prosecutor says, waving his arm toward the wall. “But inside is a Republic. This is a country not just of Roquefort, but of human rights. People have different opinions regarding globalization. Yes, there is a crisis in agriculture in France, but it’s not clear whose fault that is. Monsieur Bov├ę is a nice person, but he’s guilty! I ask for a doubled sentence for Monsieur Bov├ę, six months in jail, with three months suspended.”

The chief justice appears to be sound asleep.

THERE’S A FRENCH saying that a man without a mustache is like a meal without cheese. Beyond safeguarding both of these traditions, Bov├ę has figured out a central truth: If you’re a Frenchman and you want to save the planet, talking about food is the best way to do it.

Bov├ę’s countrymen, almost unanimously, see the health hazards of foot-and-mouth and mad cow as the tip of a dangerous American-style malbouffe iceberg. Over half the food we blithely buy in U.S. supermarkets contains genetically modified organisms, most of them unlabeled. A third of our corn and half our soybeans contain cross-species genes. French food, on the other hand, has a veritable caste system of labeling—from the prestigious Label Rouge, which distinguishes the most superlative wine, cheese, chicken, and beef, to the honorable Appellation Origine Controll├ęe, which protects not only Champagne and Roquefort, but Camargue bulls, ├Äe de R├ę potatoes, and Proven├žal lavender. Forget passing off a genetically modified product: GMOs are rarely grown in France, and must be identified as such. More than 60 percent of French markets have agreed not to sell them at all.

To Bov├ę and indeed most Frenchmen, the debate is about nothing less than cultural survival: Will France become more like the rest of the world, or will the rest of the world become more like France? The European backlash against genetically engineered crops may prove futile; globalization may be unstoppable. Still, European countries are growing more nationalist and protectionist, not less, in the face of the foot-and-mouth epidemic, which is good news for antiglobalists like Bov├ę. “We don’t want a handful of farmers providing a cover of rustic authenticity by looking after a few hedges, flowers, and birds—a sort of cardboard-cutout countryside,” he warns.

But if the French have an inherent distrust of inauthenticity, they are equally suspicious of showmanship. “Bov├ę is serious, but like everyone who becomes a media symbol, he becomes quite ridiculous at the same time,” says Paris food writer Benedict Beauge. “What is it Bov├ę believes in?” asks Antoine Jacobsohn, a Franco-American who sits on the board of the Museum of Vegetable Culture, which does exist in Paris. “Targeting the McDonald’s was a good idea, but…I’d like to see him promoting an image of terroir, not just destroying things.” Although, thinking for a moment, he adds, “I liked it when he pissed on imported wheat.”

On March 22, Bov├ę was ordered to serve three months for the McDonald’s affair, a sentence he will appeal again. For the hostage crisis, he got off with a fine of 6,000 francs, about $850. Jail wasn’t so bad the first time, says Bov├ę; the guards, unionists themselves, were easy on him, and the other inmates brought him Nescaf├ę. “Jail is jail,” Bov├ę says from his cell phone on his way to Sweden to address its farmers’ union. “If I have to go, I have to go. The only problem is that the pipe is not allowed, only cigarettes.”

In the meantime his travel plans remain space-age. He planned to disrupt the Summit of the Americas in Quebec in April, then head down to Mexico to meet with Zapatista leader Subcommandante Marcos. In July, he will be at the Group of Eight Summit in Genoa, Italy, and he’ll hit Qatar in November for the next WTO meeting. Then maybe West Africa, where he has fans. The sheep farmer has grown too busy to farm.