THERE WAS A SUDDEN FLASH of light, and then Rod Liberal was falling, his world gone black. He tried to yell, but he was only screaming in his mind. Not yet, it’s not my time, he was thinking. When Liberal’s climbing rope finally snapped taut, his front tooth slammed into solid rock and chipped—but at least he knew he was alive.

rod liberal

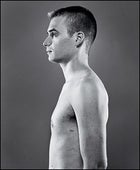

FLASH FORWARD: Rod Liberal has finally recovered from the lightning strike that nearly killed him, but the scars—including one below his left armpit—remain.

FLASH FORWARD: Rod Liberal has finally recovered from the lightning strike that nearly killed him, but the scars—including one below his left armpit—remain.rod liberal

HAVEN ON EARTH: Rod and Jody Liberal, at home in Layton, Utah, with their two-year-old son, Kai

HAVEN ON EARTH: Rod and Jody Liberal, at home in Layton, Utah, with their two-year-old son, Kai“I woke up and all I saw was sky and my feet,” says Liberal. “I had to break something to know I was still there.”

It was 3:35 p.m. on July 26, 2003. Liberal, 30, a software developer based in Idaho Falls, Idaho, and 12 friends and co-workers had been climbing Friction Pitch, a 5.5 route on the Grand Teton, in Wyoming’s Grand Teton National Park. They’d been trying to make it down before the dark clouds rolled in. But the storm had other ideas: It hit the climbers like an explosion.

Now Liberal was hanging upside down 800 feet below the 13,770-foot summit. He couldn’t see his companions—or the devastation they’d been dealt. Erica Summers, a 25-year-old mother of two from Idaho Falls and the second person on Liberal’s rope team, had been killed instantly on a ledge above him. Sitting beside Summers, racked with grief, was her 27-year-old husband, Clinton, who’d been leading the climb; he’d been briefly knocked unconscious and had sustained third-degree burns on one leg. Scattered below, around the base of Friction Pitch, Jacob Bancroft, 27, Reagan Lembke, 25, and Justin Thomas, 29, had suffered serious injuries, including broken bones, ripped tendons, and severe burns.

Liberal floated in and out of consciousness, and he wasn’t sure how long he’d been hanging there when he heard the voice of Bob Thomas, 51, a climber in his group, relaying what had happened to the team via their two-way radios. “We’ve been struck by lightning,” Thomas reported. “We’ve got one deceased, maybe two.”

That’s when Liberal started screaming for real. “I wanted to let them know I was alive,” he says.

With the whir and whumping of helicopters, a complex rescue mission was set into action, one that would take more than eight hours and involve more than 45 Teton park rangers and emergency workers. The third time a chopper arrived, ranger Craig Holm, 35, rappelled out of it and appeared at Liberal’s side, asking him about his three-month-old son, Kai, to gauge how lucid he was. After four and a half hours dangling on the rope, Liberal was barely alive. His pulse was so weak that Holm could detect only a faint beat from his carotid artery.

Just before 9 p.m., Liberal was flown to the Idaho Falls–based Eastern Idaho Regional Medical Center, where he was stabilized before being choppered to the burn ward at the University of Utah Hospital, in Salt Lake City. He’d suffered second-degree burns on his right leg, stomach, chest, and left arm and had a host of secondary problems caused by the massive voltage slamming into his body and coursing through his veins, heart, nerves, spinal cord, and brain. For the next three weeks he was in a medically induced coma, with a tracheotomy tube in his throat to help him breathe and a chest tube to drain the fluid filling his right lung. His kidneys shut down, and he developed pneumonia and pancreatitis. His fall, meanwhile, had caused internal hemorrhaging in his right hip, and his right leg was severely swollen from the tourniquet effect inflicted by his harness after the fall. His doctors weren’t sure he was going to make it.

“The only thing that kept me alive on the mountain was the thought of my new son growing up without a father,” says Liberal. “What I went through after I was struck were the worst days of my life.”

THE TETON INCIDENT may be more dramatic than most, but outdoor lightning strikes are all too common. Lightning is one of the most lethal forms of weather, zapping and injuring 3,081 Americans in the past ten years and leaving 490 DOA. Many experts think lightning strikes are underreported and that the number of victims could actually be much higher. Floods and tornadoes may kill more people in a given season, but lightning is the ultimate meteorological sucker punch: No one can predict where it will hit.

According to Ron Holle, a Tucson-based lightning-safety expert and former research meteorologist for the National Severe Storms Laboratory, in Norman, Oklahoma, the overall number of lightning-related deaths has been declining for more than half a century, reflecting the fact that fewer people are farming or working outside. What’s significantly increasing, meanwhile, is fatalities among hiking and adventure enthusiasts, thanks to the rising popularity of biking, climbing, and similar pursuits. “This is definitely an upward trend, especially in western states,” says Holle, who is currently a consultant for Vaisala, a Finnish company that builds weather equipment and operates a nationwide lightning-detection network in the U.S. “Just look at Wyoming. Almost all lightning deaths there are outdoor-recreation-related.” This summer, the risk was made dramatically clear when a lightning strike killed a teenage Boy Scout and an assistant scoutmaster in California’s Sequoia National Park; five days later, another teenage scout was killed in Utah’s Uinta Mountains. Nine scouts were injured in the two incidents.

Watching an electrical storm from afar is a natural spectacle, but there’s good reason to feel fear when it comes closer. If you could stop any one of the 25 million flashes that touch down in the U.S. each year—gargantuan electrical discharges created by the buildup of excess negative charges in clouds—you’d feel heat of up to 50,000 degrees Fahrenheit, five times hotter than the surface of the sun. A single flash can carry more than 100 million volts, the equivalent of 833,000 people sticking paper clips into electrical outlets. And lightning has been known to roam as far as 15 miles from the storm that bred it before striking from a clear blue sky. One minute you’re the master of a fourteener; the next you’re on a gurney with a tube down your throat and a lifetime of recovery ahead of you—if you even survive the current ripping through your nervous system, which can instantly shut down your heart.

Liberal was lucky that his coma spared him the intense pain from lightning-inflicted nerve damage and severe burns. After six weeks in the hospital, with repeated dialysis treatments and 21 days on a respirator, his kidneys, lungs, and pancreas began to function normally, and his swollen right leg shrank back to natural size. He was moved from intensive care, having lost 30 pounds from his five-foot-eight, 150-pound frame, and began four months of extensive physical therapy to relearn how to sit up and walk. After three weeks, he regained the use of his left arm and could walk with a cane.

Now, two years after the incident, most people can’t tell that Liberal was injured unless he goes shirtless, which reveals pink scar tissue on his arm and left side, or they notice the tracheotomy scar on his throat. He’s regained most of his normal movement. But the former amateur hockey player can no longer skate competitively, because his proprioception—the ability to know where one’s body is in space—is off; and his right foot is constantly numb. “I still shudder when I hear kids outside playing in the rain,” he says.

FOR MANY LIGHTNING VICTIMS, the psychological recovery presents the biggest challenge. According to Dr. Nelson Hendler, the clinical director of Stevenson, Maryland’s Mensana Clinic—and one of the few U.S. doctors specializing in lightning’s long-term effects on the body—dozens of symptoms can develop after a strike, including sleep apnea, short-term-memory loss, uncontrolled rage, and personality changes.

The problems can be so debilitating—and are so often misunderstood—that victims have formed a support group, Lightning Strike & Electric Shock Survivors International. At one of the group’s recent gatherings in Orlando, Florida, Raúl E. Damas, a 62-year-old runner and rock climber from Miami Beach, Florida, described the post-traumatic stress he went through and the struggle to put his life back together after he got hit while jogging in New Jersey in 2000. Others recounted their problems with worsening memory loss, a side effect of chronically interrupted sleep cycles.

In the aftermath of his lightning strike, Liberal was agitated and fearful, and his short-term memory was fried. He suffered fits of rage and depression, and when he returned home two months following the accident, he had trouble at work—his mind couldn’t stay on task. “It put a lot of stress on my marriage,” says Liberal, who recently moved with his family to Layton, Utah. “My wife, Jody, had to take care of a new baby—and me.” Liberal used exercise and counseling to confront the emotional problems, but his short-term memory still hasn’t recovered.

Looking back, Liberal concedes that his climbing team was on the mountain too late that fateful July day, though he doesn’t blame anyone for what happened. He and his friends knew they’d gotten a late start, hitting Friction Pitch in the early afternoon—prime lightning time. “We made a series of decisions with the best intentions,” he says. “People are quick to judge.”

WHICH BRINGS US BACK to that old question: How do you protect yourself from lightning? Few of us are willing or able to do what some safety experts recommend: If you hear thunder or see a storm within six miles of your location, immediately get inside a building or car (a tent is useless). A more practical way to be prepared is to heed weather forecasts. “You need to assess your weather threat the day before your adventure,” says Richard Kithil, founder and CEO of the National Lightning Safety Institute, in Louisville, Colorado. “If you’re out in the woods for a week, then you’re out of luck.”

According to Ron Holle, you should lower the risk by getting your ride, hike, or climb over before thunderclouds appear, which typically means finishing before noon. Beyond that, Holle’s 25 years of analyzing data have brought him to a pessimistic conclusion: If you head outside, there’s nothing you can do to eliminate the danger. “Whether you stand under trees or out in the open; under a cliff or away; whatever you’re wearing or carrying, whether you squat or lie flat—you can still be hit by lightning,” he warns. “You have to treat lightning like any other natural hazard. It’s something you can’t control.”

Kithil is equally pessimistic. “Lightning safety in the outdoors is almost an oxymoron,” he says.

John Gookin, who develops programs for the Lander, Wyoming–based National Outdoor Leadership School, has a little more faith in preventive measures. He, too, advocates timing your activities to avoid afternoon thunderstorms; he also advises staying away from trees and exposed areas like summits and ridgelines, and employing “the lightning position,” a tight tuck that theoretically improves your chances. “No one’s ever died in that position,” he says. “I’d rather try it than nothing.”

Rod Liberal, for one, doesn’t plan to stay inside the rest of his life. In August, for the second anniversary of the Teton tragedy, Liberal was planning to join fellow climber Jacob Bancroft (who was also struck on Friction Pitch, suffering a severe concussion) and some of the rangers who saved their lives for a return to the Grand. “I want to see where everything happened,” Liberal says. “I want to be able to say I made it up the same route.”